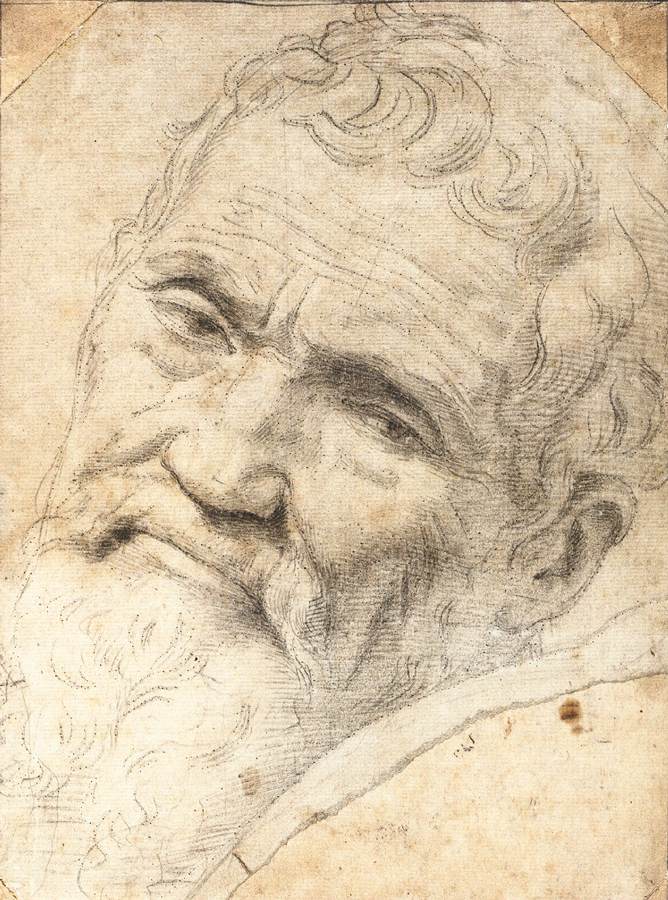

“Michelangelo. The last decades”: la mostra del British Museum dedicata ai miei ultimi trent’anni di vita

Nel 1534 avevo 59 anni e ancora in vita ero l’artista più celebre d’Europa.

Pittura, scultura e architettura non avevan più segreti per me ed ero un poeta di tutto rispetto. Fu quello l’anno in cui partii da Firenze in via definitiva alla volta di Roma. Si potrebbe pensare a un fine carriera dignitoso nella città dei papi ma a quell’età stavo per cominciare un’altra avventura incredibile: la realizzazione del Giudizio Universale che m’aveva commissionato papa Clemente VII de’ Medici, confermata poi dal successore papa Paolo III Farnese.

Dovete pensare che nel XVI secolo, 60 anni erano un’età di tutto rispetto e mai mi sarei immaginato di dover vivere altri trent’anni. Da quel momento in poi gli impegni si moltiplicarono. Il peso degli anni si faceva sentire ma avevo sempre più commissioni da condurre a termine.

I papi che si succedettero volevano mi impegnassi a realizzare qualcosa per loro. La mostra che aprirà i battenti al British Museum dal 2 maggio fino al 28 luglio 2024 sarà proprio incentrata sugli ultimi trent’anni della mia vita: “Michelangelo. The last decades”

Tornando a Roma

Il primo lavoro al quale misi mano una volta tornato a Roma fu il Giudizio Universale, affrescato sopra la contro parete in mattoni inclinata che volli far realizzare sia per aumentare l’effetto prospettico dell’opera sia per evitare che troppa polvere si depositasse sopra le figure dipinte nel corso degli anni a seguire.

Dipingere in affresco non era facile e richiedeva uno sforzo fisico non indifferente. Le porzioni stese di intonaco andavano poi dipinte in giornata, prima che si essiccassero e venisse meno il processo di carbonatazione che permetteva a quelle figure di divenire un tutt’uno con la parete e avere lunga vita.

Dopo aver terminato il Giudizio Universale misi mano ai due affreschi dell’attigua Cappella Paolina per Papa Paolo III ma mica era finita lì.

Nel frattempo dovevo portare avanti il cantiere della Basilica di San Pietro che poco a poco si stava edificando nel luogo doe sorgeva l’antica basilica Costantiniana.

Erano gli anni Quaranta del Cinquecento quando su un foglio, a denti stretti, annotai “Non sono un architetto” ma nonostante ciò di architettura e ne dovetti occupare eccome. Passai gli ultimi vent’anni dell’esistenza a lavorare alla cupola di San Pietro, a fare progetti per Palazzo Farnese, Porta Pia e per la risistemazione della zona del Campidoglio.

Le collaborazioni della vecchiaia

Avevo sempre preferito lavorare da solo ma con il tempo imparai a collaborare con artisti di talento. L’età che avanzava e il mio stato di salute sempre più incerto, mi convinsero ad accettare un modo di lavorare diverso.

Così mi capitò di disegnare composizioni che poi il Venusti dipinse aggiungendo dettagli frutto della propria immaginazione come per esempio La Purificazione del Tempio che io avevo disegnato e il Venusti realizzato.

Collaborare con altri mi permise di realizzare più opere: io disegnavo e loro dipingevano tavole e tele avendo la mia autorizzazione per farlo.

Per Ascanio Condivi invece realizzai il grande cartone preparatorio a grandezza naturale appena ultimato di restaurare dell’Epifania.

Il cartone, alto più di due metri e largo quasi due, lo feci avere al Condivi molto probabilmente per ringraziarlo della biografia che mi aveva scritto nel 1553. Era gli esordi della propria carriera artistica e quella fu la sua grande occasione: non era cosa da tutti ricevere in dono un mio disegno per poi tradurlo in pittura.

Il dipinto dell’Epifania realizzato da Condivi appartiene a Casa Buonarroti ma volerà direttamente a Londra in occasione di questa mostra del British Museum. Per la prima volta verrà mostrato assieme al cartone preparatorio. Il dipinto di Casa Buonarroti è stato restaurato proprio in vista dell’esposizione londinese.

Passioni e disegni privati

La mostra del British Museum proporrà ai visitatori anche uno sguardo sulla mia vita privata e sulle mie ardenti passioni.

Sebbene in molto mi dipingono come burbero e irrascibile e non senza avere alcuna ragione per farlo, ero capace anche di grandi slanci d’affetto e di essere divorato vivo da un ardente amore.

Fra i legami affettivi più significativi che ebbi durante i miei ultimi trent’anni di vita c’erano sicuramente quelli con a luce dei miei occhi Tommaso de’ Cavalieri e Vittoria Colonna. Amicizie fondamentali che mi indussero a creare opere importanti.

Per Tommaso disegnai allegorie mitologiche come per esempio la Caduta di Fetonte mentre per Vittoria Colonna pensai a Cristo sulla Croce vivo che attingeva all’immaginario intimo della riforma, evocando la tragedia e il trionfo della morte di Cristo e la redenzione dell’umanità attraverso di Lui.

La fede

Ero un cattoico devoto e mano a mano che passavano gli anni, pensavo sempre di più alla salvezza dell’anima, ai peccati che avevo commesso e alla morte. Non mi risparmiai nell’inviare grandi somme di denaro al mi nipote Lionardo a Firenze affinchè li donasse a chi più aveva bisogno.

Roma era ancora intimorita dall’impatto della Riforma nel Nord Europa che metteva in discussione tanti aspetti della dottrina cattolica e la Chiesa cattolica, dal canto suo, stava cercando di dare una risposta concreta. A quel periodo risalgono un gran numero di disegni dedicati alla Crocifissione, realizzati negli ultimi dieci anni della mia vita.

La mostra che aprirà al pubblico al British Museum dal titolo “Michelangelo. The last decades” proporrà il racconto dei miei trent’anni di carriera, tra i 59 e gli 89 anni.

Saranno presenti disegni miei ma anche lettere, poesie e altri documenti che metteranno in luce sia la mia determinazione che le mie vulnerabilità.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

“Michelangelo. The last decades”: the British Museum exhibition dedicated to my last thirty years of life.

In 1534 I was 59 years old and still alive I was the most famous artist in Europe.

Painting, sculpture and architecture no longer held secrets for me and I was a highly respected poet. That was the year in which I left Florence permanently for Rome. One could think of a dignified end to my career in the city of the popes but at that age I was about to begin another incredible adventure: the creation of the Last Judgment that Pope Clement VII de’ Medici had commissioned me to do, later confirmed by his successor Pope Paul III Farnese.

You have to think that in the 16th century, 60 was a very respectable age and I would never have imagined having to live another thirty years. From that moment on, the commitments multiplied. The weight of the years was felt but I had more and more commissions to complete.

The popes who followed each other wanted me to commit to doing something for them. The exhibition which will open its doors at the British Museum from 2 May until 28 July 2024 will focus on the last thirty years of my life: “Michelangelo. The last decades”

Returning to Rome

The first work I started to work on once I returned to Rome was the Last Judgment, frescoed above the inclined brick counter-wall that I wanted to have built both to increase the perspective effect of the work and to prevent too much dust from settling on the figures. painted over the following years.

Painting in fresco was not easy and required considerable physical effort. The portions of plaster applied had to be painted the same day, before they dried and the carbonation process which allowed those figures to become one with the wall and have a long life was lost.

After finishing the Last Judgment I worked on the two frescoes in the adjacent Pauline Chapel for Pope Paul III but that wasn’t the end of it.

In the meantime I had to carry on the construction site of St. Peter’s Basilica which was gradually being built on the site where the ancient Constantinian basilica once stood.

It was the 1540s when on a piece of paper, through clenched teeth, I wrote down “I am not an architect” but nevertheless about architecture and I had to deal with it indeed. I spent the last twenty years of my life working on the dome of St. Peter’s, making plans for Palazzo Farnese, Porta Pia and for the redevelopment of the Capitol area.

The collaborations of old age

I had always preferred to work alone but over time I learned to collaborate with talented artists. My advancing age and my increasingly uncertain state of health convinced me to accept a different way of working.

So I happened to draw compositions which Venusti then painted, adding details from his own imagination such as, for example, The Purification of the Temple which I had drawn and the Venusti created.

Collaborating with others allowed me to create more works: I drew and they painted panels and canvases having my authorization to do so.

For Ascanio Condivi, however, I created the large life-size preparatory cartoon of the Epiphany which had just been completed.

The cartoon, more than two meters high and almost two meters wide, I sent to Condivi most likely to thank him for the biography he had written for me in 1553. It was the beginning of his artistic career and that was his great opportunity: it was not something to everyone will receive one of my drawings as a gift and then translate it into painting.

The Epiphany painting created by Condivi belongs to Casa Buonarroti but will fly directly to London for this British Museum exhibition. For the first time it will be shown together with the preparatory cartoon. The Casa Buonarroti painting was restored in view of the London exhibition.

Private passions and designs

The British Museum exhibition will also offer visitors a glimpse into my private life and my ardent passions.

Although many portray me as gruff and irascible and not without having any reason to do so, I was also capable of great outbursts of affection and of being devoured alive by an ardent love.

Among the most significant emotional bonds I had during the last thirty years of my life were certainly those with Tommaso de’ Cavalieri and Vittoria Colonna. Fundamental friendships that led me to create important works.

For Tommaso I drew mythological allegories such as the Fall of Phaeton while for Vittoria Colonna I thought of the living Christ on the Cross which drew on the intimate imagery of the reform, evoking the tragedy and triumph of Christ’s death and the redemption of humanity through Him .

Faith

I was a devout Catholic and as the years passed, I thought more and more about the salvation of my soul, the sins I had committed and death. I did not spare myself in sending large sums of money to my nephew Lionardo in Florence so that he could donate them to those who needed them most.

Rome was still frightened by the impact of the Reformation in Northern Europe which called into question many aspects of Catholic doctrine and the Catholic Church, for its part, was trying to give a concrete response. A large number of drawings dedicated to the Crucifixion, made in the last ten years of my life, date back to that period.

The exhibition that will open to the public at the British Museum entitled “Michelangelo. The last decades” will tell the story of my thirty-year career, between the ages of 59 and 89.

There will be drawings of mine but also letters, poems and other documents that will highlight both my determination and my vulnerabilities.

For the moment, your always Michelangelo Buonarroti greets you and will meet you in the next posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

8,00 €

-

Il Dipinto del giorno: la Madonna della Seggiola di Raffaello e quella cornice non più originale

🇮🇹Il dipinto del giorno che vi propongo oggi, in occasione della Festa della Mamma, è la Madonna della Seggiola di Raffaello… 🇬🇧The painting of the day that I propose to you today, on the occasion of Mother’s Day, is the Madonna della Seggiola by Raphael…

-

L’Estasi nella Sagrestia Nuova che rischia di trasformare in pietra il visitatore

🇮🇹Era il 1545 quando il Tribolo iniziò a sovrintendere ai lavori della Sagrestia Nuova e per i viaggiatori e gli artisti fu molto più semplice aver accesso a quel luogo ricco di miei capolavori… 🇬🇧It was 1545 when Tribolo began to supervise the works of the New Sacristy and it was much easier for travelers…

-

Le opere più note dell’Ascensione di Cristo: Giotto, Mantegna, Perugino, Tintoretto e Rembrandt

🇮🇹Oggi la Chiesa ricorda l’Ascensione di Cristo al Cielo, un evento fondamentale della fede cristiana. Viene celebrato 40 giorni esatti dopo la Pasqua e segna il ritorno trionfante di Gesù al Padre, dopo la sua vittoria sulla morte e la risurrezione dai morti… 🇬🇧Today the Church remembers the Ascension of Christ into Heaven, a fundamental…

1 commento »