5 febbraio 1519: il giorno in cui feci bruciare i miei disegni

Il 5 febbraio del 1518 ricevetti una lettera pesante come un macino da Roma. A scriverla fu Leonardo il Sellaio, uomo fidato, che avevo lasciato a controllare la mia casa e a verificare che fosse eseguito l’ordine che avevo dato: distruggere i miei cartoni e i miei disegni.

Non era un capriccio ma una decisione presa con piena coscienza.

La scelta prima di partire da Roma

Poco tempo prima ero tornato a Roma da Firenze per discutere con papa Leone X de’ Medici della facciata di San Lorenzo. Durante quel breve soggiorno, guardando i fogli accumulati negli anni, presi una decisione netta: una gran quantità di studi doveva sparire per sempre, senza lasciare tracce tangibili.

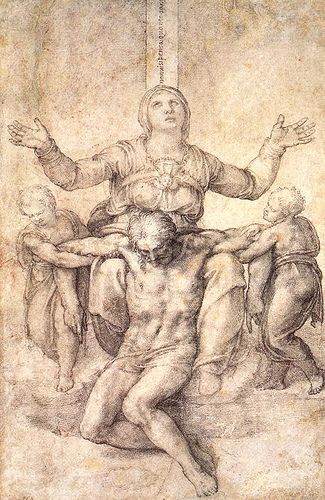

Tra quei cartoni vi erano con ogni probabilità anche quelli preparatori per la volta della Cappella Sistina: disegni che avevo usato per trasferire le figure sull’intonaco fresco, mediante lo spolvero o l’incisione a seconda dei casi.

Erano fogli di lavoro, strumenti. Non opere da mostrare a chi sarebbe arrivato dopo di me. Non volevo divenissero di dominio pubblico.

Così ordinai ai miei collaboratori di bruciarli poi ripartii per Firenze, lasciando a loro l’incarico.

La lettera del 5 febbraio

Qualche settimana dopo, giunse la lettera di Leonardo. Mi scriveva con tristezza, ma anche con quella fedeltà che sempre m’aveva dimostrato: «E’ dichono avere ari tutti que’ chartoni, ma non chredo di tutti. Doghomi, ma la volontà vostra s’a’ a seguire, e io per piacervi meterei del mio sangue.»

Mi diceva che avevano bruciato quei cartoni, anche se sospettava che qualcuno potesse averne salvato qualcuno. Si doleva, ma la mia volontà, scriveva, doveva essere seguita.

Così, di quei fogli non rimase che un mucchio di cenere.

Non fu l’unico falò

Quello del 1519 non fu l’unico rogo. Negli anni successivi ne feci fare altri, mandando in fumo un gran numero di disegni.

Non volevo che si vedessero i miei tentativi, le prove, gli errori. L’opera finita doveva parlare da sé, senza svelare le fatiche e i ripensamenti che l’avevano preceduta. I disegni erano strumenti del mestiere, non ricordi da conservare.

Un’eredità ridotta alle ceneri

Molto probabilmente, tra quei fogli distrutti, c’erano centinaia di studi: figure, progetti, idee che oggi nessuno potrà più vedere.

Di tutto ciò che disegnai in vita mia, di fogli tutto sommato ne sono rimasti pochi. Il resto è diventato cenere, per mia stessa volontà.

Eppure, le opere sono ancora lì: nella pietra, nell’intonaco, nel marmo.

I fogli potevano bruciare. Ciò che avevo creato, no.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

February 5, 1519: The Day I Burned My Drawings

On February 5, 1518, I received a heavy letter from Rome. It was written by Leonardo il Sellaio, a trusted man, whom I had left to guard my house and ensure that the order I had given was carried out: to destroy my cartoons and drawings.

It wasn’t a whim, but a fully conscious decision.

The Decision Before Leaving Rome

Shortly before, I had returned to Rome from Florence to discuss the façade of San Lorenzo with Pope Leo X de’ Medici. During that brief stay, looking at the papers accumulated over the years, I made a clear decision: a large quantity of studies had to disappear forever, leaving no tangible trace.

Among those cartoons were most likely the preparatory ones for the Sistine Chapel ceiling: drawings I had used to transfer the figures onto the fresh plaster, using either spolvero or incisions as appropriate.

They were worksheets, tools. Not works to show to those who would come after me. I didn’t want them to become public knowledge.

So I ordered my collaborators to burn them, then left for Florence, leaving the task to them.

The letter of February 5

A few weeks later, Leonardo’s letter arrived. He wrote to me with sadness, but also with the loyalty he had always shown me: “I say I have all those drawings, but I don’t believe in them all. Doghomi, but your will must be followed, and to please you I would shed my blood.”

He told me they had burned those cartoons, even though he suspected someone might have saved some of them. He was sorry, but my will, he wrote, had to be followed.

So, of those sheets, only a pile of ashes remained.

It wasn’t the only bonfire

The one in 1519 wasn’t the only bonfire. In the following years, I had others made, destroying a great number of drawings.

I didn’t want my attempts, trials, and errors to be seen. The finished work had to speak for itself, without revealing the labors and second thoughts that preceded it. The drawings were tools of the trade, not memories to be preserved.

A legacy reduced to ashes

Most likely, among those destroyed sheets of paper, there were hundreds of studies: figures, plans, ideas that no one will ever see again.

Of everything I drew in my life, very few sheets of paper remain. The rest turned to ashes, by my own will.

And yet, the works are still there: in the stone, in the plaster, in the marble.

The sheets of paper could burn. What I had created, could not.

For now, yours truly, Michelangelo Buonarroti bids you farewell and invites you to see him in future posts and on social media.