6 settembre 1944: il trafugamento della Madonna di Bruges

La notte compresa fra il 6 e il 7 settembre del 1944, fu trafugata dalla chiesa di Notre Dame il Belgio, la Madonna di Bruges che avevo scolpito secoli prima per i Musucron, una ricca famiglia di mercanti fiamminghi.

Con la complicità che solo le tenebre possono dare, un gruppo di soldati al comando di Hitler rubarono quel capolavoro facendolo scomparire nel nulla, lasciando nello sconforto fedeli e ogni persona di buon senso che non può tollerare il vedersi strappare pezzo dopo pezzo la propria identità storica e culturale.

La mia Madonna, che in precedenza era stata trafugata dalle truppe di Napoleone, fu rubata dalla chiesa di Notre dame di Bruges, in Belgio e fatta partire prima per nave e poi per terra fino ad arrivare alle miniere di sale di Altaussee, nel cuore dell’Austria.

Assieme a lei era stati nascoste altre 6500 opere fra dipinti, sculture, libri miniati e molti altri oggetti preziosi provenienti da ogni angolo d’Europa.

La scelta delle miniere di sale di Altaussee come nascondiglio per le opere d’arte non fu casuale. Era il luogo ideale per tentare di salvarle dalla distruzione dalla guerra ma le cose si sa, a volte cambiano repentinamente il corso della storia.

Quelle miniere furono all’inizio individuate dai musei viennesi per stipare le loro opere fin dal principiare degli scontri armati per tentare di salvarle dalla distruzione dei bombardamenti.

Scavate in orizzontale all’interno della montagna, avrebbero resistito senza grandi problemi a qualsiasi bombardamento aereo. Il salgemma presente assorbiva l’umidità e le temperature rimanevano costantemente comprese fra i 4 e gli 8°C durante tutto il corso dell’anno.

Sculture, stampe e quadri potevano essere conservate così in ottime condizioni mentre gli oggetti metallici come le armature, avrebbero dovuto essere ricoperti di uno strato di grasso per evitare la corrosione.

Poco dopo però Hitler requisì le miniere per metterci dentro tutte le opere che aveva fatto trafugare per allestire alla fine del conflitto il museo dei suoi sogni, a Linz. Nel giro di due soli anni arrivarono a custodire 6577 dipinti, 230 disegni e acquerelli, 946 stampe e altri 137 oggetti di grande valore.

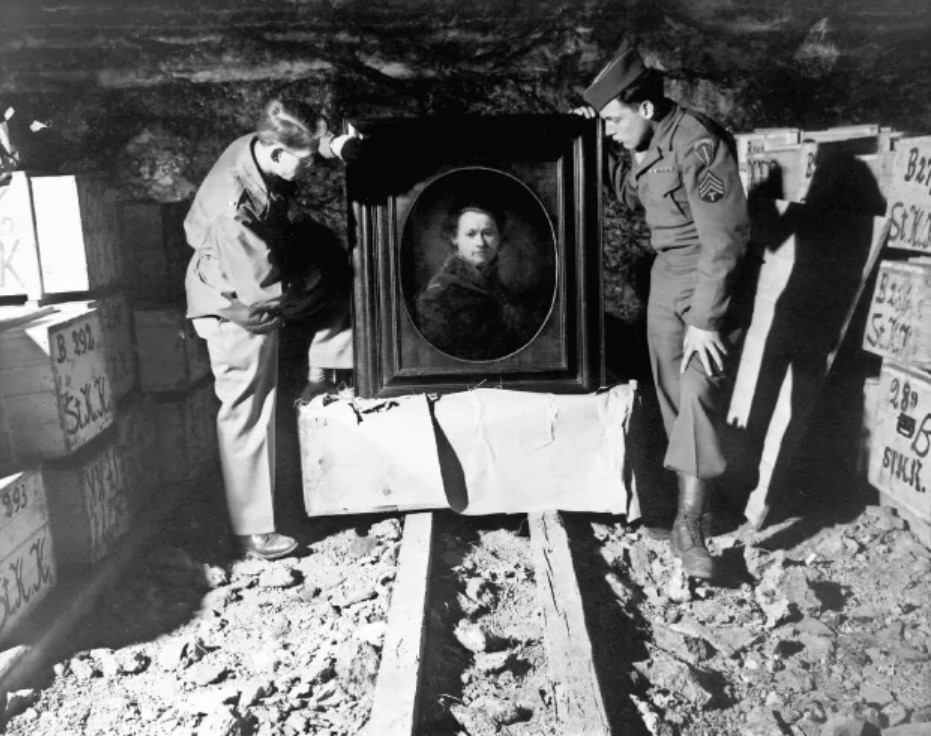

La Madonna di Bruges fu rinvenuta dai Monuments Man nel maggio del 1945 e, a poca distanza da que capolavoro, ritrovarono opere incredibili come l’Astronomo di Vermeer che era stato trafugato dal Museo del Louvre, tanto per citare un’opera straordinaria.

Fra le varie opere stipate, tornarono alla luce diversi cassoni con la dicitura: “marmi, maneggiare con cautela”. In realtà al loro interno i Monuments Man trovarono degli ordigni che sarebbero fatti esplodere distruggendo tutte le opere in caso di disfatta: un’operazione folle che avrebbe distrutto per sempre secoli di storia dell’arte.

Per tornare nella sua collocazione originaria, la Madonna di Bruges dovette attendere fino al 12 novembre del 1945, quando fu di nuovo posta nicchia in marmi neri della Chiesa di Notre Dame di Bruges dopo aver fatto una breve tappa nel Palazzo Provinciale in piazza Markt.

Per il momento il vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

September 6, 1944: the theft of the Madonna of Bruges

On the night between 6 and 7 September 1944, the Madonna of Bruges, which I had sculpted centuries earlier for the Musucrons, a wealthy family of Flemish merchants, was stolen from the church of Notre Dame in Belgium.

With the complicity that only darkness can give, a group of soldiers under Hitler’s command stole that masterpiece making it disappear into thin air, leaving the faithful and every person of common sense who cannot tolerate having their historical identity torn piece by piece in despair. and cultural.

My Madonna, which had previously been stolen by Napoleon’s troops, was stolen from the church of Notre Dame in Bruges, Belgium and sent first by ship and then by land to the salt mines of Altaussee, in the heart of the ‘Austria.

Together with her, another 6500 works had been hidden, including paintings, sculptures, illuminated books and many other precious objects from every corner of Europe.

The choice of the Altaussee salt mines as a hiding place for the works of art was not accidental. It was the ideal place to try to save them from destruction by war, but things are known, sometimes they suddenly change the course of history.

Those mines were initially chosen by the Viennese museums to cram their works from the beginning of the armed clashes to try to save them from destruction by bombing.

Dug horizontally inside the mountain, they would have resisted any aerial bombardment without major problems. The rock salt absorbed the humidity and the temperatures remained constantly between 4 and 8°C throughout the year.

Sculptures, prints and paintings could thus be kept in excellent condition while metal objects such as armor would have to be covered with a layer of grease to prevent corrosion.

Shortly after, however, Hitler requisitioned the mines to put inside all the works that he had stolen to set up the museum of his dreams at the end of the conflict, in Linz. Within just two years they came to keep 6577 paintings, 230 drawings and watercolours, 946 prints and 137 other objects of great value.

The Madonna of Bruges was found by the Monuments Man in May 1945 and a short distance from this masterpiece they found incredible works such as Vermeer’s Astronomer which had been stolen from the Louvre Museum, just to mention an extraordinary work.

Among the various works crammed, several chests came to light with the words: “marbles, handle with caution”. In reality, the Monuments Man found bombs inside them that would be detonated, destroying all the works in the event of defeat: a crazy operation that would destroy centuries of art history forever.

To return to its original location, the Madonna of Bruges had to wait until November 12, 1945, when it was once again placed in a black marble niche in the Church of Notre Dame in Bruges after a brief stop in the Provincial Palace in Markt square.

For the moment, your Michelangelo Buonarroti greets you by making an appointment for the next posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support U

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

8,00 €

-

5 marzo 1534: muore il Correggio, il pittore delle illusioni prospettiche che anticiparono il Barocco

🇮🇹Il 5 marzo 1534 si spegne nella sua città natale uno dei pittori più straordinari del Rinascimento italiano: Antonio Allegri da Correggio, conosciuto semplicemente come Correggio… 🇬🇧On March 5, 1534, one of the most extraordinary painters of the Italian Renaissance died in his hometown: Antonio Allegri da Correggio, known simply as Correggio…

-

“Strabilio for Gaza”: a Villanuova sul Clisi una serata di arte, circo e solidarietà

Una serata di arte e solidarietà arriva a Villanuova sul Clisi. Venerdì 6 marzo alle ore 20.30 il Teatro Corallo ospiterà “Strabilio for Gaza”, un evento speciale che unisce cinema, danza e circo contemporaneo per raccontare la realtà della Striscia di Gaza e raccogliere fondi a sostegno delle organizzazioni umanitarie impegnate sul campo…

-

5 marzo 1570: Cosimo I de’ Medici incoronato Granduca di Toscana nella Cappella Sistina

🇮🇹Il 5 marzo 1570 Cosimo I de’ Medici venne solennemente incoronato Granduca di Toscana da Papa Pio V Ghislieri nella Cappella Sistina… 🇬🇧On March 5, 1570, Cosimo I de’ Medici was solemnly crowned Grand Duke of Tuscany by Pope Pius V Ghislieri in the Sistine Chapel…