3-4 agosto 1944: la notte in cui furono fatti saltare i ponti a Firenze

Firenze non può dimenticare quella terribile notte tra il 3 e il 4 agosto del 1944, quando i ponti sull’Arno vennero fatti saltare in aria uno dopo l’altro ad eccezion fatta di Ponte Vecchio, nonostante fosse stato minato come tutti gli altri.

L’avvocato Gaetano Casoni nel suo diario annota il momento esatto in cui le SS cominciarono a far brillare le mine che avevano posizionato ai piloni dei ponti: “Da poco era cominciato ad imbrunire lievemente perché siamo nel plenilunio, quando cinque minuti avanti le ventidue è parso che un terremoto scuotesse la terra, abbiamo udito un boato prima sordo e poi fragoroso. Ci siamo guardati in faccia: evidentemente i tedeschi cominciano la loro opera di infame distruzione”.

Polvere, fumo e macerie era ciò che rimase di quei ponti che univano le due parti della città di qua e di là dall’Arno.

L’avanzata degli eserciti Alleati dopo lo sfondamento della Linea Gustav e la liberazione di Roma aveva fatto prendere misure estreme ai comandi nazisti. Saccheggi, rappresaglie, stragi delle comunità attraversate dalle truppe in ritirata erano all’ordine del giorno.

Il fiume Arno permetteva di creare una barriera naturale nel tentativo di rallentare l’avanzata degli Alleati ma era necessario far saltare i ponti e così fu fatto.

Il pomeriggio del 29 luglio del 1944, sui muri della città venne affissa l’ordinanza di sgombero dei Lungarni e il giorno seguente l’avviso fu pubblicato sul quotidiano La Nazione.

In serata il cardinale Elia dalla Costa si riunì assieme al vice prefetto Gigli, al soprintendente delle belle Arti, al console svizzero Steinhäuslin e al vice podestà De Francisci. Oramai le autorità fasciste erano fuggite e quei rappresentanti delle istituzioni rimasti tentarono di salvare il salvabile.

Misero una serie di assicurazioni date precedentemente da Kesserling e Hitler per tutelare della città e le consegnarono il giorno successivo al colonello Fuchs ma non ricevettero alcuna risposta.

Decine di migliaia di persone dovettero lasciare in fretta e furia la propria casa già sapendo che non avrebbero più avuto modo di tornarci.

In molti trovarono rifugio a Palazzo Pitti, presso il carcere delle Murate, caserme e chiese ma anche nelle case di parenti e amici che abitavano in altre zone della città o nei dintorni.

Il mattino del 3 agosto il comando tedesco ordinò ai fiorentini di non uscire di casa. La situazione non era delle più lusinghiere e fu chiaro a tutti che qualcosa di disastroso stava per accadere da un momento all’altro.

Durante la notte fra il 3 e il 4 agosto i ponti minati crollarono uno dopo l’altro. Le esplosioni che si susseguirono ridussero in macerie Ponte alle Grazie e Ponte alla Vittoria. Ponte Santa Trinita, tanto era ben strutturato che parve opporre un’ultima ma ferma resistenza a quelle esplosioni.

Dopo la terza carica fatta brillare crollò anche lui in Arno.

“Ogni due ore circa si rinnovano gli scoppi di grossissime mine, i boati, i colpi che sembrano determinati da proiettili destinati a cadere su di noi; nuove nuvole si innalzano paurose quasi a precipitare l’enormità del disastro”.

Casoni

Ponte Vecchio fu l’unico risparmiato: tanto era amato dal Furer che decisero di lasciarlo al suo posto. Questa è una delle versioni che si racconta ma potrebbe essercene un’altra forse ancor più calzante.

Ponte Vecchio come tutti gli altri ponti era già stato minato e gli ordigni erano pronti a farlo saltare in aria. Sembra che due lavoratori delle botteghe orafe di Ponte Vecchio, prima di lasciare la zona, notarono il punto di allaccio delle carice di dinamite e li staccarono senza farsi vedere.

Così al momento dell’esplosione le cariche non furono detonate. In merito a questa vicenda sono stati ritrovati degli interessanti documenti, resi pubblici nel libro “Di pietra e d’oro. Il Ponte Vecchio di Firenze, sette secoli di storia e di arte“ a cura di Cristina Acidini, Antonio Natali, Lucia Barocchi, Elisabetta Nardinocchi e Marco Ferri.

“Alla prima esplosione sul cader della notte scrollò appena le spalle e restò in piedi. Allora i manigoldi ritentarono di far saltare i piloni, ma invano.

Allora lavorarono alla disperata tutta la notte ad avviluppare in una gabbia d’esplosivo l’intera arcata: e solo così, vicino all’alba, riuscirono a farlo saltare. Questo affannarsi notturno di ombre crudeli contro il ponte che resisteva somiglia ad una scena di tortura: anche il vecchio ponte, colpevole di aver resistito, fu condannato a perire di morte lenta, sotto i supplizi dei Tedeschi

Piero Calamandrei racconta come fu fatto crollare Ponte Santa Trinita, uno dei ponti più belli di Firenze

Le esplosioni furono violentissime tanto da far arrivare pezzi di Ponte Santa Trinita fino in via Cerretani.

Al mattino Firenze si svegliò con uno scenario mai visto prima: dilaniata e divisa a metà, con i Lungarni devastati e macerie ovunque.

Passarono gli anni e poco a poco quella Firenze devastata fu ricostruita. Ponte Santa Trinita che a ragion veduta era considerato il ponte più bello della città, riconquistò l’aspetto originario con la riedificazione del 1952 sotto la direzione dei lavori di Riccardo Gizdulich, coadiuvato da Elimio Brizzi.

Le sculture che decoravano il ponte furono ripescate sul fondo dell’Arno ma la testa della Primavera era stata trafugata. Il fiorentino Fantucci lanciò una campagna per ritrovarla e alla fine i renaioli riuscirono a ritracciarla, dopo che Bellini aveva annunciato una ricompensa di 5mila dollari per chi la restituisse a Firenze.

Per il momento il vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

3-4 August 1944: the night the bridges in Florence were blown up

Florence cannot forget that terrible night between 3 and 4 August 1944, when the bridges over the Arno were blown up one after the other, with the exception of Ponte Vecchio, despite having been mined like all the others.

In his diary, the lawyer Gaetano Casoni notes the exact moment in which the SS began to detonate the mines they had placed on the bridge pylons: “It had just begun to get dark slightly because we are in the full moon, when five minutes before ten it seemed that an earthquake was shaking the earth, we heard a first dull and then thunderous roar. We looked at each other: evidently the Germans are beginning their work of infamous destruction”.

Dust, smoke and rubble was what remained of those bridges that united the two parts of the city on both sides of the Arno.

The advance of the Allied armies after the breakthrough of the Gustav Line and the liberation of Rome had caused the Nazi commands to take extreme measures. Looting, reprisals, massacres of the communities crossed by retreating troops were the order of the day.

The Arno river made it possible to create a natural barrier in an attempt to slow down the advance of the Allies but it was necessary to blow up the bridges and so it was done.

On the afternoon of 29 July 1944, the ordinance for the eviction of the Lungarni was posted on the walls of the city and the following day the notice was published in the newspaper La Nazione.

In the evening, Cardinal Elia dalla Costa met together with the vice prefect Gigli, the superintendent of fine arts, the Swiss consul Steinhäuslin and the vice podestà De Francisci. By now the fascist authorities had fled and those representatives of the institutions who remained tried to save what could be saved.

They placed a series of assurances previously given by Kesserling and Hitler to protect the city and delivered them the next day to Colonel Fuchs but received no response.

Tens of thousands of people had to hurriedly leave their homes knowing they would never be able to return.

Many found refuge in Palazzo Pitti, at the Murate prison, barracks and churches but also in the homes of relatives and friends who lived in other areas of the city or in the surrounding area.

On the morning of August 3, the German command ordered the Florentines not to leave their homes. The situation was not the most flattering and it was clear to everyone that something disastrous was about to happen at any moment.

During the night between 3 and 4 August the mined bridges collapsed one after the other. The explosions that followed reduced Ponte alle Grazie and Ponte alla Vittoria to rubble. Ponte Santa Trinita, it was so well structured that it seemed to offer a last but firm resistance to those explosions.

After the third charge fired he too collapsed in the Arno.

“Every two hours or so the explosions of very large mines are renewed, the roars, the blows that seem to be caused by projectiles destined to fall on us; new clouds rise fearfully as if to precipitate the enormity of the disaster”.

Casoni

Ponte Vecchio was the only one spared: it was so loved by the Furer that they decided to leave it in its place. This is one of the versions that is told but there could be another one that is perhaps even more fitting.

Ponte Vecchio like all the other bridges had already been mined and the devices were ready to blow it up. It seems that two workers of the goldsmith shops of Ponte Vecchio, before leaving the area, noticed the connection point of the dynamite sedges and detached them without being seen.

Thus at the time of the explosion the charges were not detonated. In regards to this affair, some interesting documents have been found, made public in the book “Di pietra e d’oro. The Ponte Vecchio in Florence, seven centuries of history and art” edited by Cristina Acidini, Antonio Natali, Lucia Barocchi, Elisabetta Nardinocchi and Marco Ferri. “At the first explosion at nightfall he just shrugged his shoulders and remained standing. Then the scoundrels tried again to blow up the pylons, but in vain.

So they worked desperately all night to envelop the entire arch in a cage of explosives: and only in this way, near dawn, did they manage to blow it up. This nocturnal struggle of cruel shadows against the bridge that resisted resembles a scene of torture: even the old bridge, guilty of having resisted, was condemned to perish a slow death, under the tortures of the Germans.

Piero Calamandrei tells how Ponte Santa Trinita, one of the most beautiful bridges in Florence, was brought down

The explosions were so violent that pieces of Ponte Santa Trinita reached Via Cerretani.

In the morning Florence woke up with a scenario never seen before: torn apart and divided in half, with the Lungarni devastated and rubble everywhere.

Years passed and little by little that devastated Florence was rebuilt. Ponte Santa Trinita, which was rightly considered the most beautiful bridge in the city, regained its original appearance with the rebuilding in 1952 under the direction of the works by Riccardo Gizdulich, assisted by Elimio Brizzi.

The sculptures that decorated the bridge were fished up from the bottom of the Arno but the head of Primavera had been stolen. The Florentine Fantucci launched a campaign to find it and in the end the sanders managed to track it down, after Bellini had announced a reward of 5,000 dollars for anyone who returned it to Florence.

For the moment, your Michelangelo Buonarroti greets you by making an appointment for the next posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

8,00 €

-

Quel busto è mio? Nemmeno dopo due fiaschi di Trebbiano l’avrei scolpito così

🇮🇹E tutti a buttarsi a pesce sulla nuova fantomatica scoperta del busto del Cristo Salvatore in Sant’Agnese fuori le mura a Roma. Sarebbe mio quel Cristo lì, con quel volto inespressivo, anonimo e con quello sguardo perduto?… 🇬🇧And everyone’s jumping on the newly discovered bust of Christ the Savior in Sant’Agnese fuori le mura in…

-

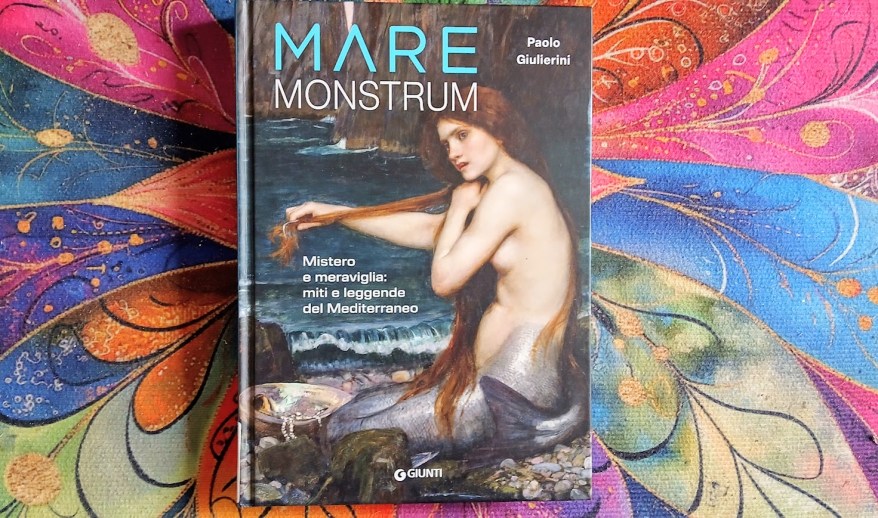

Mare Monstrum di Giulierini: il Mediterraneo oscuro che spiega il nostro presente

Con il libro Mare Monstrum, Paolo Giulierini, già direttore del Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, propone un viaggio colto e avvincente nel cuore del Mediterraneo, raccontato non come semplice spazio geografico ma come organismo vivo, mutevole e spesso inquietante…

-

Giornata Internazionale della Donna: 8 marzo 2026 musei e siti culturali statali gratis per tutte le donne

🇮🇹Domenica 8 marzo, le donne celebrano la loro giornata accedendo gratuitamente a musei, parchi e monumenti storici italiani. Un’occasione da non perdere… 🇬🇧On Sunday, March 8th, women celebrate their day with free admission to Italian museums, parks, and historical monuments. An opportunity not to be missed…

1 commento »