Il foglio con gli studi per la Cupola di San Pietro

In questo foglio che vi propongo, oggi appartenente al Teylers Museum, ho lasciato traccia dei miei tormenti e delle mie visioni per la cupola di Basilica di San Pietro. U un campo di battaglia tra memoria e invenzione, tra Firenze e Roma, tra ciò che vidi da giovane e ciò che volli superare in vecchiaia.

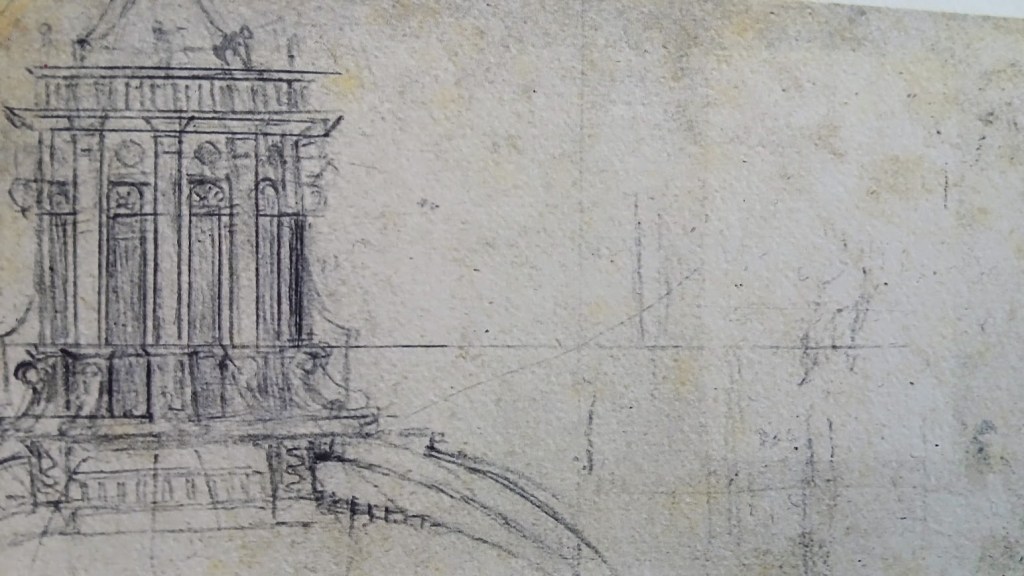

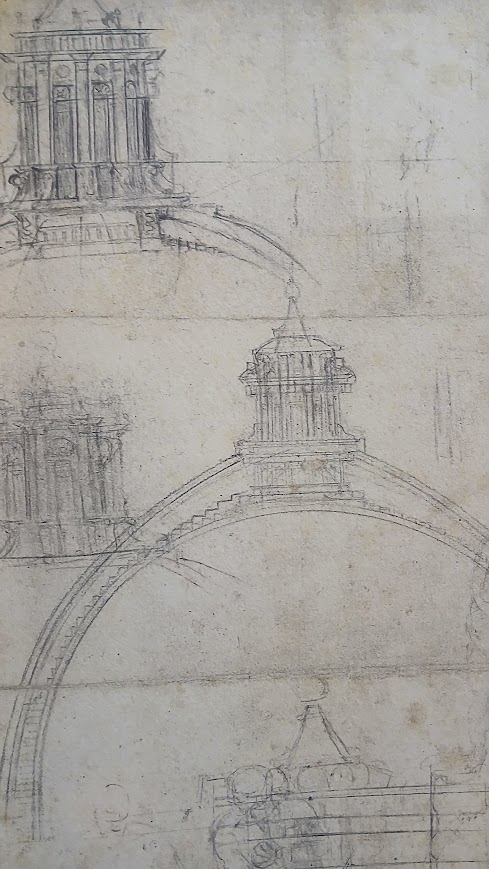

La matita nera scorre accanto alle linee di costruzione. Si vedono ancora le tracce della punta del compasso, segni vivi del pensiero che misura, confronta, tenta. Gli angoli superiori e quello in basso a sinistra sono rinfacciati, quasi a contenere l’energia di uno studio che non voleva restare confinato nei margini.

Luglio 1547: la lettera a Lionardo e le misure della Cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore

Nel luglio del 1547 scrissi a mio nipote Lionardo, a Firenze, chiedendogli l’altezza della cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore e quella della lanterna. Non era curiosità, ma necessità. Dal 1546 ero stato nominato architetto della fabbrica di San Pietro da papa Paolo III Farnese e dovevo misurarmi con un’eredità immensa.

La cupola del Brunelleschi mi accompagnava da tempo nella memoria. La doppia calotta, la curva esterna leggermente ogivale, la divisione in sezioni con quei costoloni, le volute e il motivo a conchiglia della lanterna, la copertura a cono: tutto questo riaffiora nei miei schizzi. Non ho mai avuto però l’intenzione di copiarla. Ero alla ricerca di una forma più slanciata, una tensione verticale che parlasse a Roma e al mondo intero.

Il disegno e la nascita della Cupola di San Pietro

Alcuni studiosi collocarono temporalmente questo foglio con gli studi dopo il 1547, forse nei primi anni Cinquanta. Altri, come Joannides, pensarono al 1559, quando sperimentavo soluzioni più verticali per il coronamento dell’edificio, assai simili a quella poi realizzata.

La curva esterna che tracciavo, concepita come quinto acuto, corrisponde con sorprendente esattezza al profilo della cupola odierna, misurato nei tempi moderni con strumenti di cui allora non potevo immaginare l’esistenza. Eppure quella forma era già tutta nel mio pensiero.

La cupola fu portata a termine solo dopo la mia morte, da Giacomo della Porta, tra il 1588 e il 1590. Non mutò il mio progetto: l’impostazione l’avevo già stabilita io e la mia volontà non fu tradita.

Le differenze con Firenze e le ricerche sulla lanterna

Se da un lato il mio spirito si nutriva della lezione fiorentina, dall’altro me ne distaccavo con decisione. Nel foglio si vedono due diversi punti di partenza per il guscio interno e per quello esterno.

La lanterna fu oggetto di molte prove. Sedici sono oggi le finestre e le colonne accoppiate che la coronano. Ma nei miei studi si leggono soluzioni differenti: otto finestre in alto a sinistra, dieci nel disegno principale della cupola, dodici in basso. Cercavo il numero giusto, l’equilibrio tra luce e struttura, tra ritmo e gravità.

Il piccolo schizzo staccato e la figura nascosta

Nel 1952 venne staccato da questo foglio un piccolo schizzo di portale, oggi al Teylers Museum, che alcuni avevano messo in relazione con la Porta Pia. Ma esso non aveva rapporto diretto con questi studi, e la sua presenza aveva tratto in inganno sulla datazione.

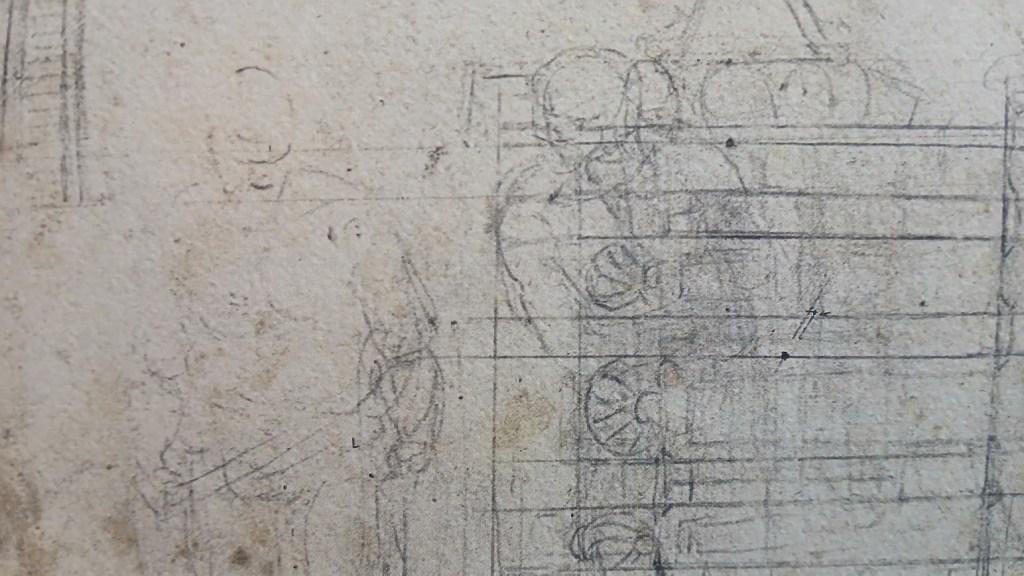

Tolto quel frammento, riapparve nel punto in cui era incollato una piccola figura, che ricorda il Cristo del mio Giudizio Universale. Forse un primo pensiero, forse un’eco di quell’immagine terribile e gloriosa che ancora mi abitava.

In basso si scorge una figura maschile, coperta da due schizzi sovrapposti per la lanterna, uno tracciato in senso trasversale e l’altro con il cono in verticale. Qualcuno volle riconoscervi uno studio per un giovane della Crocifissione di San Pietro, nella Cappella Paolina. Ma le spalle, la postura, la tensione del corpo non coincidono. E poi, entrambe le figure furono quasi interamente ricalcate dal verso del foglio, segno che il mio pensiero tornava, insisteva, trasformava.

Chi lo osserva oggi questo foglio vede linee, numeri, curve. Io vi vedo fatica, dubbio, preghiera. E la certezza che la cupola, prima di innalzarsi nel cielo, deve nascere molte volte sulla carta.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

The sheet with the studies for St. Peter’s Dome

In this sheet I present to you, now owned by the Teylers Museum, I have left traces of my torments and visions for the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica. It is a battlefield between memory and invention, between Florence and Rome, between what I saw as a youth and what I wanted to surpass in old age.

The black pencil runs alongside the construction lines. The traces of the compass point are still visible, vivid signs of the thought that measures, compares, and attempts. The upper corners and the lower left corner are pointed, as if to contain the energy of a study that did not want to remain confined to the margins.

July 1547: the letter to Lionardo and the measurements of the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore

In July 1547, I wrote to my nephew Lionardo, in Florence, asking him the height of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore and that of the lantern. It was not curiosity, but necessity. In 1546, I had been appointed architect of St. Peter’s by Pope Paul III Farnese, and I had to contend with an immense legacy.

Brunelleschi’s dome had long been in my memory. The double shell, the slightly ogival external curve, the division into sections with those ribs, the volutes and shell motif of the lantern, the conical roof: all of this resurfaces in my sketches. However, I never intended to copy it. I was searching for a more slender form, a vertical tension that would speak to Rome and the entire world.

The Design and Creation of St. Peter’s Dome

Some scholars have dated this sketch after 1547, perhaps in the early 1550s. Others, like Joannides, have suggested 1559, when I was experimenting with more vertical solutions for the building’s crown, very similar to the one that ultimately came to fruition.

The external curve I traced, conceived as a pointed arch, corresponds with surprising accuracy to the profile of the dome today, measured in modern times with instruments whose existence I could not have imagined at the time. Yet that form was already entirely in my mind.

The dome was completed only after my death, by Giacomo della Porta, between 1588 and 1590. He did not change my plan: I had already established the layout, and my will was not betrayed.

The Differences with Florence and Research on the Lantern

While on the one hand my spirit was nourished by the Florentine lesson, on the other I decisively distanced myself from it. In the drawing, two different starting points can be seen for the internal and external shells.

The lantern was the subject of many experiments. Today, there are sixteen windows and the paired columns that crown it. But in my studies, different solutions can be seen: eight windows at the top left, ten in the main design of the dome, twelve at the bottom. I was searching for the right number, the balance between light and structure, between rhythm and gravity.

The small detached sketch and the hidden figure

In 1952, a small sketch of a portal, now in the Teylers Museum, was detached from this sheet. It had no direct connection with these studies, and its presence had misled the dating.

After that fragment was removed, a small figure reappeared where it had been glued, reminiscent of the Christ from my Last Judgement. Perhaps a first thought, perhaps an echo of that terrible and glorious image that still haunted me.

At the bottom, a male figure can be seen, covered by two overlapping sketches for the lantern, one drawn transversally and the other with the cone vertical. Some have claimed it to be a study for a young man from the Crucifixion of St. Peter, in the Pauline Chapel. But the shoulders, the posture, the tension of the body do not match. And then, both figures were almost entirely traced from the back of the sheet, a sign that my thought was returning, insistent, transforming.

Whoever looks at this sheet of paper today sees lines, numbers, curves. I see effort, doubt, prayer. And the certainty that the dome, before rising to the heavens, must be born many times on paper.

For now, yours truly, Michelangelo Buonarroti bids you farewell, and invites you to see him in future posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €