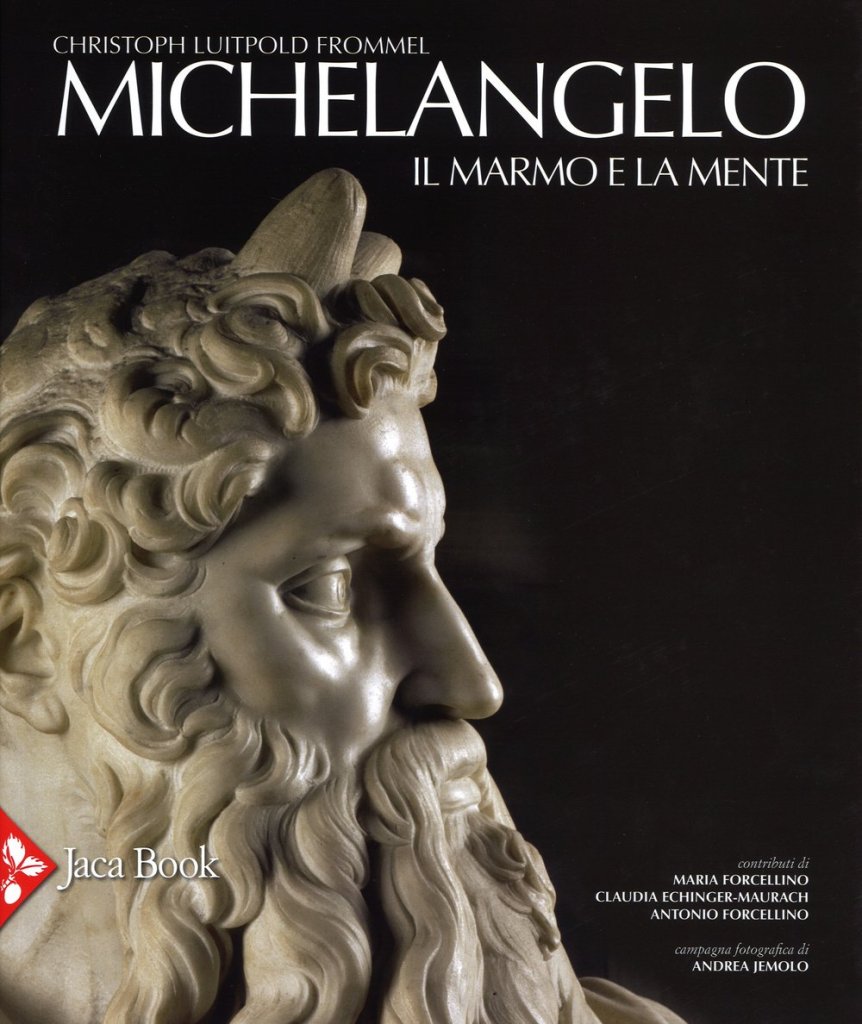

Quando e come cambiai posizione al Mosè

Il Mosè è una di quelle opere che tutti conoscono ma in pochi hanno ben chiara tutta la sua storia: dalla genesi fino ai giorni vostri, con il cambiamento di posizione in corso d’opera.

Iniziai a metter mano alla scultura agli inizi del 1514. Due anni più tardi però tornai a Firenze e l’opera rimase a Roma non ultimata.

Solo 25 anni dopo ebbi modo di rimetterci mano ma ben presto mi resi conto che la sua posa statica e frontale non mi convinceva più. In tutti quegli anni di acqua ne era passata sotto i ponti. Avevo realizzato tanti lavori nel frattempo come le Tombe dei Medici nella Sagrestia Nuova della basilica di San Lorenzo e gli affreschi del Giudizio Universale.

Il dinamismo dei corpi del Giudizio e quelle figure che riprodussi in ogni atteggiamento possibile, non mi permettevano di consegnare nelle mani del mondo una scultura statica, priva di quel movimento che oramai era un segno distintivo delle mie creazioni.

Non mi persi certo ’animo e con qualche accorgimento ben studiato, cambiai la posizione del capo del Mosè: se prima guardava dritto davanti a sé, avrebbe poi mirato verso sinistra, mettendo in modo una torsione dinamica in tutto il resto del corpo.

Non mi fermai lì però. Le gambe che prima erano direzionate nello stesso modo del capo, le girai a forza di scalpellate o meglio, ne lasciai una posizionata com’era e l’altra la aprii verso l’esterno, sfruttando il materiale che ancora avevo a disposizione.

A scoprire per primo gli stravolgimenti dell’opera fu Christoph Frommel che trovò un documento coevo redatto da un anonimo nel quale veniva annotato questo cambiamento a dir poco radicale.

“Che li aveva svoltata la testa et sopra la punta del naso gli haveva lasciata un poco della gota con la pelle vecchia, che certo fu cosa mirabile ne credo quasi che a me stesso considerando la cosa quasi che impossibile”.

Durante il restauro della tomba di Giulio II, il restauratore e studioso Antonio Forcellino si rese perfettamente conto degli accorgimenti che avevo messo in pratica per voltare la scultura.

Se guardate bene l’opera vi accorgerete che la barba viene tirata verso destra perché a sinistra oramai non c’era più materiale sufficiente.

Per far torcere i corpo dovetti abbassare il trono su cui è seduto di ben 7 centimetri mentre, per far arretrare il piede sinistro, ridimensionai il ginocchio corrispondente di circa 5 centimetri rispetto all’altro.

Per deviare lo sguardo dello spettatore e non fare notare la differenza dimensionale fra le due ginocchia, scolpii un ricco panneggio fra le due gambe. La scultura vista di spalle ancora presenta parte della vecchia cintura che davanti è stata completamente rimossa.

L’evidente cambiamento ha dato adito a supposizioni, teorie e fantasie più o meno ardite. Freud sosteneva che il Mosè arricciolasse con la mano la barba per domare la propria furia e per salvare le tavole dinanzi alla visione del vitello d’oro.

Frommel, con una versione secondo me più calzante, sosteneva che il mostrasse la nuca all’altare della Chiesa di San Pietro in Vincoli come monito contro chi nel transetto venerava le catene di San Pietro per ottenere le indulgenze: una sorta di vitello d’oro di altri tempi. La venerazione delle reliquie per gli Spirituali, gruppo al quale aderivo, era considerata superstizione più che devozione.

“Il pathos del dramma interiore si traduce nelle volute dei capelli, nel turgore della fronte increspata di rughe e nello sguardo schiacciante che cade dalle orbite incavate; ma il fremito delle forti labbra sensuali dgli angoli calati, il corrucciato arricciamento del naso esprimono il sovrano disdegno che questo gigante prova dinanzi alle turpitudini umane”

-Charles de Tolnay-

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

When and how I changed the position of Moses

Moses is one of those works that everyone knows but few have a clear idea of its entire history: from the genesis of the tomb of Julius II to the present day.

I began to work on the sculpture at the beginning of 1514. Two years later, however, I returned to Florence and the work remained in Rome unfinished.

Only 25 years later did I have the opportunity to work on it again but I soon realized that its static and frontal pose no longer convinced me. In all those years, a lot of water had passed under the bridge. I had created many works in the meantime, such as the Medici Tombs in the New Sacristy of the Basilica of San Lorenzo and the frescoes of the Last Judgement.

The dynamism of the bodies of the Last Judgement that I reproduced in every possible position did not allow me to deliver into the hands of the world a static sculpture, devoid of that movement that by now was a distinctive sign of my creations.

I certainly did not lose heart and with some well-studied tricks, I changed the position of Moses’ head: if before he looked straight ahead, he would then aim to the left, thus creating a dynamic torsion in the rest of the body.

I did not stop there, however. The legs that were previously directed in the same way as the head, I turned by chiseling them or rather, I left one positioned as it was and I opened the other outwards, using the material that I still had available.

The first to discover the distortions of the work was Christoph Frommel who found a contemporary document written by an anonymous person in which this change was noted, to say the least, radical.

“That he had turned his head and above the tip of his nose he had left a little of his cheek with old skin, which certainly was a wonderful thing and I almost believe it to myself considering the thing almost impossible”.

During the restoration of the tomb of Julius II, the restorer and scholar Antonio Forcellino was fully aware of the measures I had taken to turn the sculpture.

If you look closely at the work you will notice that the beard is pulled to the right because there was no longer enough material on the left.

To twist the body I had to lower the throne on which he is sitting by a good 7 centimeters while, to move the left foot back, I resized the corresponding knee by about 5 centimeters compared to the other.

To divert the viewer’s gaze and not to point out the dimensional difference between the two knees, I sculpted a rich drapery between the two legs. The sculpture seen from behind still has part of the old belt that has been completely removed from the front.

The evident change has given rise to more or less daring suppositions, theories and fantasies. Freud claimed that Moses curled his beard with his hand to tame his fury and to save the tablets from the vision of the golden calf.

Frommel, with a version that I think is more fitting, claimed that he showed his neck at the altar of the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli as a warning against those who venerated the chains of St. Peter in the transept to obtain indulgences: a sort of golden calf from another era.

The veneration of relics for the Spirituals, a group to which I belonged, was considered superstition rather than devotion.

“The pathos of the interior drama is translated into the curls of the hair, the turgidity of the forehead creased with wrinkles and the crushing gaze that falls from the sunken eye sockets; but the quiver of the strong sensual lips with the dropped corners, the frowning wrinkle of the nose express the sovereign disdain that this giant feels in the face of human turpitude” -Charles de Tolnay-

For the moment, the ever-your Michelangelo Buonarroti bids you farewell, making an appointment with you in the next posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €