15 novembre 1553: il ritrovamento della Chimera ad Arezzo

Era il 15 novembre del 1553 quando alcuni operai al lavoro per edificare le fortificazioni ad Arezzo, vicino a porta San Lorentino, trovarono l’antica Chimera in bronzo di origine etrusca.

Fusa approssimativamente tra il V e il IV secolo avanti Cristo, per ben poco tempo rimase ad Arezzo. Il Granduca Cosimo I de’ Medici, appena ebbe la notizia del ritrovamento, pretese fosse portata a Palazzo Vecchio.

La Chimera non era integra o quasi, come la vedete oggi ma si trovava in uno stato assai frammentario tanto che in un primo momento si ebbe l’idea che potesse raffigurare un leone.

Gli studiosi alla corte di Cosimo I ben presto si resero però conto conto che si trattava di una Chimera, grazie anche all’osservazione di numerose monete greche e romane presenti proprio nella collezione granducale.

L’opera fu sottoposta a un restauro con il risaldamento delle zampe anteriori e di quella posteriore sinistra, al momento del ritrovamento staccate dal corpo centrale.

Cosimo I era un appassionato di antichità e di capolavori. Il Cellini narra che passava le serate in sua compagnia per ripulire l’opera adoperando attrezzatura da orafo.

Il Granduca volse a suo favore quella straordinaria scoperta, considerandola come un simbolo del suo dominio sugli avversari fino al momento sconfitti.

La Chimera ritrovata traeva origine dal mito greco di Bellerofonte che la uccise e fu il suo aspetto ad attrarre così tanto le grazie di Cosimo I.

Infatti lui riuscì a rivederci condensate tutte le virtù medicee: la forza nel corpo del leone e la maestosità del suo aspetto, la feconda creatività e la ricchezza nella testa di capra e l’astuzia del serpente nella coda che però la Chimera aveva perduto.

Infatti in un’incisione realizzata nel primi anni del Settecento, Thomas Dempster la riprodusse proprio senza coda.

Venne integrata solo nel 1785, quando lo scultore pistoiese Francesco Carradori rimodellò la parte mancante, posizionando erroneamente il serpente nell’atto di mordere un corno della capra.

Cosimo I fece collocare la Chimera ritrovata nella Sala di Leone X e in un secondo momento preferì portarla nel suo studiolo di Palazzo Pitti.

Nel 1718 l’opera fu trasferita agli Uffizi poi, nel 1870, al Palazzo della Crocetta, sede del Museo Archeologico di Firenze, dove tutt’oggi si trova.

In questi giorni però la Chimera è tornata alla città in cui fu ritrovata: Arezzo. L’opera è stata inserita nel percorso espositivo della mostra ‘Vasari. Il Teatro delle virtù’, dedicata al 450° anniversario dalla morte del mio caro amico Giorgio Vasari.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

November 15, 1553: the discovery of the Chimera in Arezzo

It was November 15, 1553 when some workers working to build the fortifications in Arezzo, near Porta San Lorentino, found the bronze Chimera of Etruscan origin.

Cast approximately between the 5th and 4th centuries BC, very little remained in Arezzo. Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, as soon as he heard the news of the discovery, demanded that it be taken to Palazzo Vecchio.

The Chimera was not intact or almost, as you see it today but was in a very fragmented state so much so that at first people had the idea that it could represent a lion.

Scholars at the court of Cosimo I soon realized that it was a Chimera, thanks also to the observation of numerous Greek and Roman coins present in the grand ducal collection.

The work was restored with the re-welding of the front legs and the left rear one, which had been detached from the central body at the time of discovery.

Cosimo I was passionate about antiquities and masterpieces. Cellini says that he spent evenings in his company cleaning the work using goldsmith’s tools.

The Grand Duke turned that extraordinary discovery to his advantage, considering it a symbol of his dominion over his opponents who had been defeated until then.

The rediscovered Chimera had its origins in the Greek myth of Bellerophon who killed it and it was its appearance that attracted the graces of Cosimo I so much. In fact, he managed to see all the Medici virtues condensed in it: the strength in the lion’s body and the majesty of its appearance, the fertile creativity and wealth in the goat’s head and the cunning of the serpent in the tail that the Chimera had lost.

In fact, in an engraving made in the early eighteenth century, Thomas Dempster reproduces it without a tail. In fact, it was only integrated in 1785, when the Pistoia sculptor Francesco Carradori remodeled the missing part, mistakenly positioning the snake in the act of biting a goat’s horn.

Cosimo I had the rediscovered Chimera placed in the Hall of Leo X and later preferred to take it to his study in Palazzo Pitti.

In 1718 the work was transferred to the Uffizi then, in 1870, to the Palazzo della Crocetta, home of the Archaeological Museum of Florence, where it is still located today.

In recent days, however, the Chimera has returned to the city where it was found: Arezzo. The work is in fact included in the exhibition itinerary of the show ‘Vasari. The Theater of Virtues’, dedicated to the 450th anniversary of the death of my dear friend Giorgio Vasari.

For the moment, yours truly Michelangelo Buonarroti bids you farewell, making an appointment to see you in the next posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €

-

Egon Schiele, genio e scandalo: al cinema il docufilm evento sulla Vienna ribelle del Novecento

TABÙ. Egon Schiele arriva al cinema il 20, 21 e 22 aprile con La Grande Arte al Cinema: un docufilm evento sulla vita e l’arte del genio ribelle della Vienna del Novecento…

-

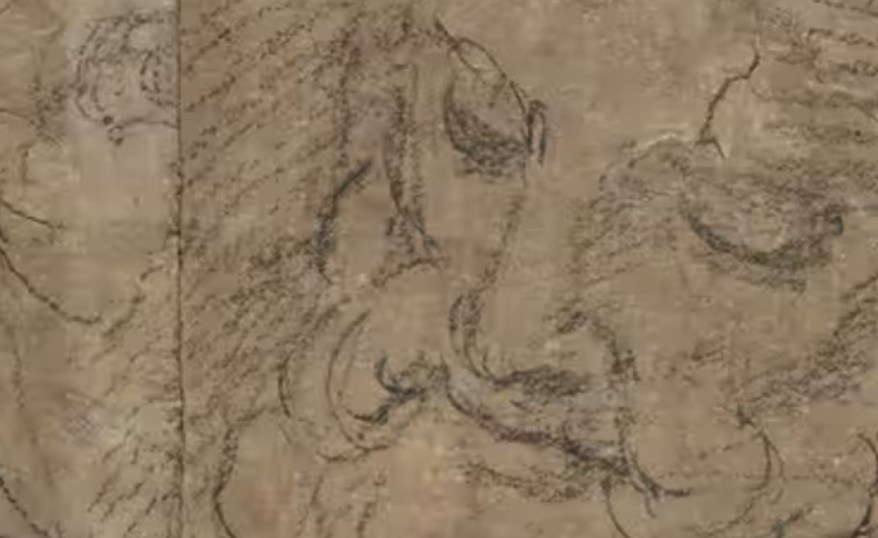

Nei miei versi, il dolore d’amore diventa poesia

🇮🇹Un foglio tra disegni. Qualche verso scritto quasi di nascosto. E un dolore che attraversa i secoli. 🇬🇧A sheet of paper among drawings. A few verses written almost in secret. And a pain that spans the centuries.

-

Parmigianino e il disegno che divide gli storici: la Sacra Famiglia che potrebbe nascondere un capolavoro perduto

🇮🇹Un disegno attribuito a Parmigianino continua a dividere gli storici dell’arte. ✨Tra incisioni cinquecentesche, collezionisti e possibili opere perdute, la Sacra Famiglia con Maddalena resta uno dei misteri più affascinanti del Rinascimento… 🇬🇧A drawing attributed to Parmigianino continues to divide art historians. ✨Among sixteenth-century engravings, collectors, and possibly lost works, the Holy Family with Mary…