Il capolavoro del Mazzuoli: il San Filippo in San Giovanni in Laterano

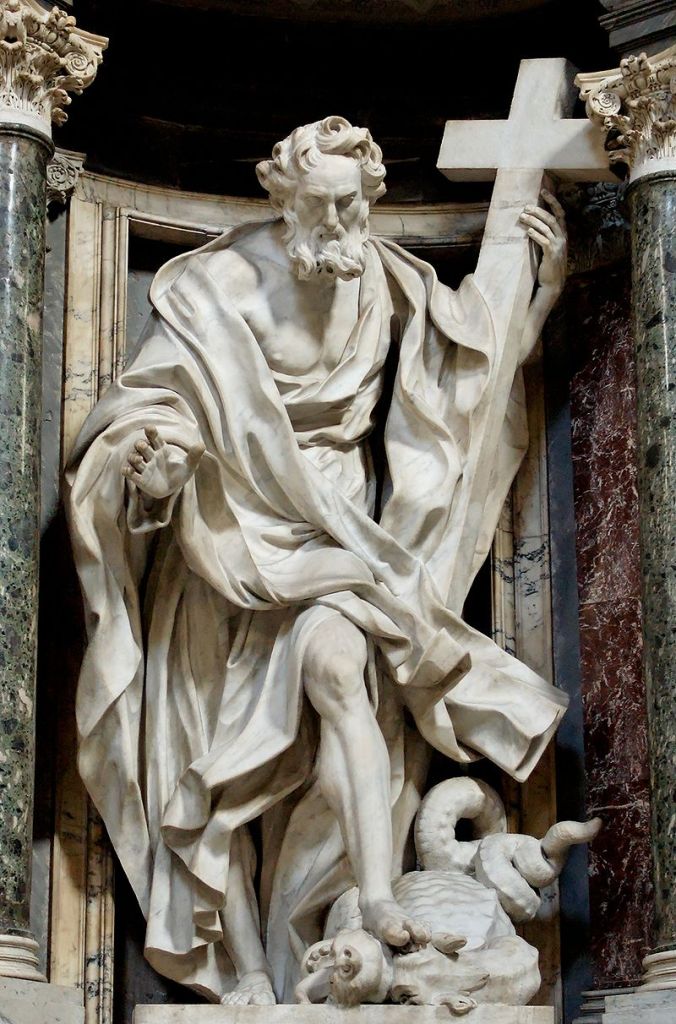

La scultura del giorno che vi propongo oggi è il maestoso San Filippo scolpito da Giuseppe Mazzuoli per la navata centrale della basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, tra il 1703 e il 1712.

Dai suoi 4 metri e 25 si innalza sopra i fedeli protendendosi in avanti. Con la mano sinistra tiene la croce mentre con il rispettivo piede schiaccia la testa al drago, simbolo del male.

La veste e il mantello dell’apostolo sono mosse dal vento per dare maggior dinamismo all’opera ma non solo. I turbinosi pensieri del Santo vengono raffigurati proprio attraverso quello svolazzare scomposto dei tessuti.

Lo scultore Giuseppe Mazzuoli, detto il Vecchio, era nato a Volterra il 5 gennaio del 1644. Il padre lo portò con sé a Siena quando si dovette trasferire per ragioni lavorative. Suo fratello maggiore Giovanni Antonio, già affermato scultore, aveva iniziato ad avviarlo allo studio dell’arte ma si rese ben presto conto del suo talento incontenibile e lo spronò ad andare a Roma per perfezionarsi.

Fu Caffà il maestro che contribuì a sviluppare notevolmente le capacità scultoree del Mazzuoli e grazie a lui riuscì a ottenere le prime importanti commissioni.

Dovete sapere che la nicchia in cui è collocato San FIlippo, alla stregua delle altre undici, fu progettata a metà del Seicento dal Borromini.

Quelle nicchie però rimasero vuote per decenni e ci volle papa Clemente XI nel 1702, sostenuto dal cardinale Benedetto Pamphilj allora arciprete della basilica, per arrivare alla commissione delle dodici sculture degli scolpiti.

Siccome non c’erano soldi a disposizione, il pontefice chiese espressamente alle famiglie romane più facoltose del tempo, di pagare di tasca le opere.

Carlo Maratta, il pittore preferito del pontefice, fu incaricato di disegnare gli apostoli da affidare poi nelle mani di abili scultori. In questo modo tutte le opere avrebbero avuto un aspetto simile, come se fossero state realizzate da un solo artista.

Pierre-Etienne Monnot, Moratti, Lorenzo Ottoni, Legros, Mazzuoli, Camillo Rusconi e Angelo de Rossi si misero al lavoro per scolpire tutti e dodici gli apostoli seguendo linee guida comuni.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

© Riproduzione riservata

Sculpture of the day: San Filippo by Mazzuoli in San Giovanni in Laterano

The sculpture of the day that I propose to you today is the majestic San Filippo sculpted by Giuseppe Mazzuoli for the central nave of the basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano, between 1703 and 1712.

From its 4 meters and 25 it rises above the faithful leaning forward. With his left hand he holds the cross while with his respective foot he crushes the head of the dragon, symbol of evil.

The robe and the cloak of the apostle are moved by the wind to give greater dynamism to the work but not only. The turbulent thoughts of the saint are depicted precisely through that uncomposed fluttering of the fabrics.

The sculptor Giuseppe Mazzuoli, known as the Elder, was born in Volterra on January 5, 1644. His father took him with him to Siena when he had to move for work reasons. His older brother Giovanni Antonio, already an established sculptor, had begun to introduce him to the study of art but soon realized his irrepressible talent and encouraged him to go to Rome to perfect himself.

It was Caffà who contributed significantly to the development of Mazzuoli’s sculptural skills and thanks to him he managed to obtain the first important commissions.

You should know that the niche in which San Filippo is placed, like the other eleven, was designed in the mid-seventeenth century by Borromini.

However, those niches remained empty for decades and it took Pope Clement XI in 1702, supported by Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj, then archpriest of the basilica, to get the commission for the twelve sculptures of the sculptors.

Since there was no money available, the pontiff expressly asked the wealthiest Roman families of the time to pay for the works out of their own pockets.

Carlo Maratta, the Pope’s favorite painter, was commissioned to draw the apostles and then entrust them to skilled sculptors. In this way, all the works would have a similar appearance, as if they had been created by a single artist.

Pierre-Etienne Monnot, Moratti, Lorenzo Ottoni, Legros, Mazzuoli, Camillo Rusconi and Angelo de Rossi set to work to sculpt all twelve apostles following common guidelines.

For the moment, yours truly Michelangelo Buonarroti bids you farewell, making an appointment to see you in the next posts and on social media.

© All rights reserved

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €

-

Quando l’Amore ti toglie a te stesso: il mio madrigale più struggente

🇮🇹“O Dio, o Dio, o Dio” così apro il mio canto, con una triplice invocazione: non è ornamento, ma necessità. La ripetizione è ansia, è tremore, è il battito stesso del cuore che chiama soccorso… 🇬🇧”O God, O God, O God!” thus I open my song, with a threefold invocation: it is not ornament, but…

-

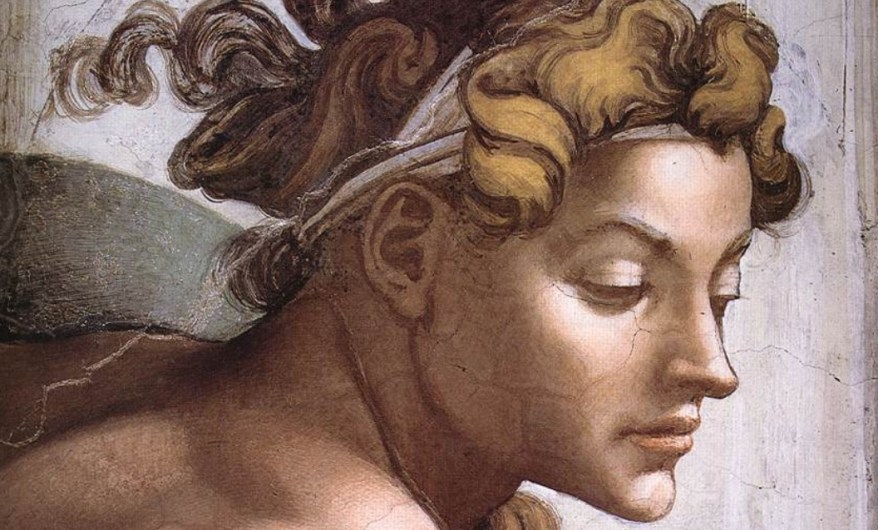

Cappella Sistina: mundator moderni per eliminare il lattato di calcio

🇮🇹I mundator contemporanei sono al lavoro per rimuovere il lattato di calcio che sta opacizzando la superficie del Giudizio Universale…. 🇬🇧Contemporary mundators are working to remove the calcium lactate that is clouding the surface of the Last Judgment….

-

Sanremo 2026: quando la musica diventa arte, da Melozzo a Caravaggio

🇮🇹Sanremo sta per cominciare e l’Italia torna a vibrare di musica. Le note hanno da sempre affascinato anche i più grandi artisti della storia: dagli angeli sospesi nel cielo di Melozzo da Forlì al violino struggente dipinto da Caravaggio, passando per la tensione manierista del Rosso Fiorentino e i sogni a colori di Marc Chagall……

1 commento »