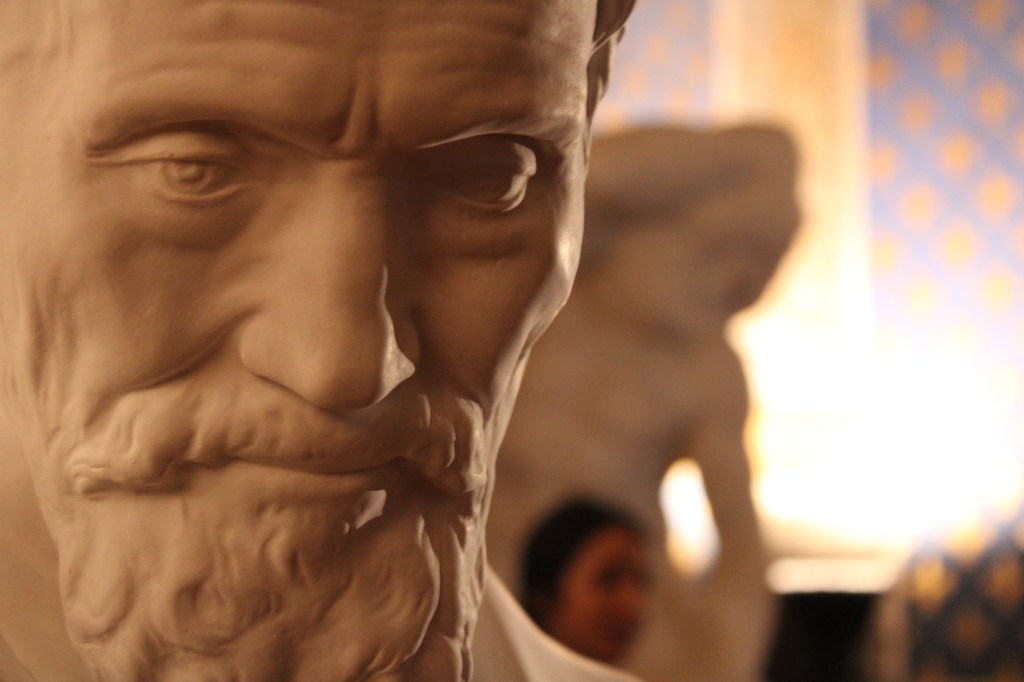

Le mie elemosine in segreto

Ho sempre fatto elemosine, fin da ragazzo. Nonostante si narra che fossi spilorcio, ho aiutato chi n’aveva bisogno senza far troppe storie.

Certo volevo esser sicuro che i danari donati andassero a beneficio di qualcuno che li necessitasse. Essere gabbato non mi piaceva. Da buon cristiano non potevo non condividere la fortuna che il cielo m’aveva dato.

Lo so, non è questo che viene narrato di me ma tutt’altro. ‘Gratuitamente avete ricevuto, gratuitamente date’ si legge nel Vangelo di Matteo. Non facevo elemosine solo per assicurarmi un transito più breve in Purgatorio, come era consuetudine ai miei tempi ma talvolta donavo per alleviare le pene terrene e celesti a chi mi stava a cuore.

“Lionardo, io ò per la tua ricievuta de’ cinque cento cinquanta scudi d’oro in oro, com’io contai qua al Bectino. Tu mi scrivi che ne darai quactro a quella donna per l’amor de Dio: che mi piace; el resto, per insino in cinquanta, ancora voglio che si dieno per l’amore di Dio, parte per l’anima di Buonarroto tuo padre e parte per la mia. Però vedi d’intendere di qualche cictadino bisognioso che abbi fanciulle o da maritare o da mectere in munistero, e dagniene, ma segretamente: e abi cura di non esser gabbato, e factene far ricievuta e mandamela; perché io parlo de’ cictadini, e che io so che a’ bisogni si vergogniono andar mendicando”

Così scrissi per esempio al mi nipote Lionardo il 3 settembre del 1547.

Volevo che donasse scudi d’oro per mio conto a una donna ‘per l’amore di Dio’ e altri soldi a qualche pover’omo che dovesse far la dote alle figlie o avesse la necessità di mandarle in monastero. No, nemmeno entrare in monastero era cosa gratuita e c’era da sborsare quattrini e fare il corredo alle future monache, sostenendo spese che non tutti potevano certo permettersi.

Raccomandavo anche al mi nipote di accertarsi che il destinatario o i destinatari dell’elemosina avessero un bisogno reale da soddisfare. Volevo inoltre che fosse fatto tutto con la massima discrezione, per non mettere in imbarazzo nessuno.

“Quando tu avessi notizia di qualche estrema miseria in qualche casa nobile, che credo che e’ ve ne sia, avisami, e chi; che per insino a cinquanta scudi io te gli manderò che gli dia per l’anima mia”, scrissi sempre a Lionardo il 15 marzo del 1549.

Esempi come questo nel mio carteggio se ne trovano molti scartabellando un po’.

“Arei caro, quando tu sapessi qualche strema miseria di qualche cictadino nobile e massimo di quelli che ànno fanciulle in casa, che tu m’avisassi, perché gli farei qualche bene per l’anima mia” riporta una lettera indirizzata al mi nipote il 20 dicembre del 1550.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui socia. ©Tutti i diritti sono riservati

All my life I have given alms

I have always given alms, since I was a boy. Although it is said that I was stingy, I helped those in need without making too much fuss.

Of course I wanted to be sure that the money donated would benefit someone who needed it. I did not like being cheated. As a good Christian I could not help but share the fortune that heaven had given me.

I know, this is not what is said about me but quite the opposite. ‘Freely you have received, freely give’ is written in the Gospel of Matthew. I did not give alms only to ensure a shorter passage in Purgatory, as was the custom in my time but sometimes I gave to alleviate the earthly and heavenly pains of those I cared about.

“Lionardo, I have for your receipt of five hundred and fifty gold scudi in gold, as I counted here at Bectino. You write to me that you will give four to that woman for the love of God: that pleases me; the rest, even fifty, I want to give for the love of God, part for the soul of Buonarroti your father and part for mine. But try to find out about some needy citizen who has girls to marry or to send to the monastery, and give them, but secretly: and take care not to be fooled, and have them received and send them to me; because I am speaking of citizens, and I know that in times of need they are ashamed to go begging”

This is what I wrote for example to my nephew Lionardo on September 3, 1547.

I wanted him to donate gold crowns on my behalf to a woman ‘for the love of God’ and other money to some poor man who had to provide a dowry for his daughters or had the need to send them to a monastery. No, not even entering the monastery was free and one had to shell out money and provide the future nuns with a trousseau, incurring expenses that certainly not everyone could afford.

I also recommended to my nephew to make sure that the recipient or recipients of the alms had a real need to satisfy. I also wanted everything to be done with the utmost discretion, so as not to embarrass anyone.

“When you hear of some extreme poverty in some noble house, which I believe there is, let me know, and who; for up to fifty scudi I will send them to you to give them for my soul”, I wrote to Leonardo on March 15, 1549.

Examples like this can be found in my correspondence by rummaging around a bit.

“I would be pleased, if you knew of some extreme misery of some noble citizen and especially of those who have girls in their house, that you inform me, because I would do him some good for my soul” reports a letter addressed to my nephew on December 20, 1550.

For the moment, yours always Michelangelo Buonarroti greets you, making an appointment with you in the next posts and on social networks. ©All rights reserved

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €

-

Pasqua nell’arte: 7 capolavori che raccontano la resurrezione tra luce, dramma e speranza

🇮🇹La Pasqua raccontata dai grandi artisti. Dal Rinascimento al Novecento, la resurrezione ha ispirato capolavori straordinari: ecco 7 opere che trasformano luce, dramma e speranza in immagini indimenticabili… Easter as told by great artists. From the Renaissance to the twentieth century, the resurrection has inspired extraordinary masterpieces: here are 7 works that transform light, drama,…

-

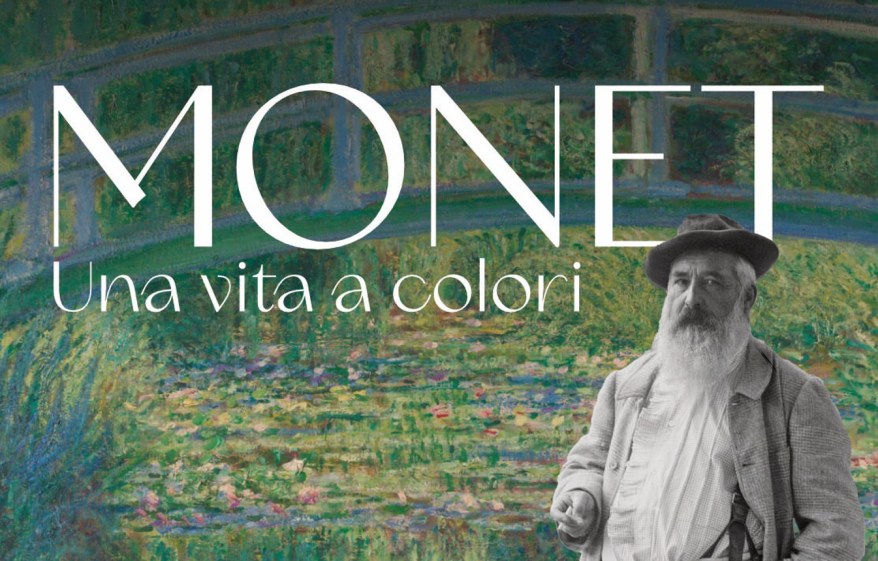

Il mondo di Monet prende vita sul palco: la nuova tournée teatrale che celebra il maestro della luce

🇮🇹Debutta nel 2026 lo spettacolo teatrale “Monet. Una vita a colori” di Marco Goldin: un viaggio immersivo tra arte, musica e immagini per celebrare i 100 anni dalla morte di Claude Monet… 🇬🇧Marco Goldin’s theatrical production “Monet. A Life in Color” will debut in 2026: an immersive journey through art, music, and images to celebrate…

-

Donatello al Museo: visite guidate ai capolavori del Rinascimento al Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Firenze

Dal 14 marzo 2026 l’Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore inaugura una nuova esperienza dedicata agli amanti dell’arte: un ciclo di visite guidate alla scoperta dei capolavori di Donatello conservati nel Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Firenze…