Madonna della Rosa di Raffaello: influenze e Curiosità Storiche

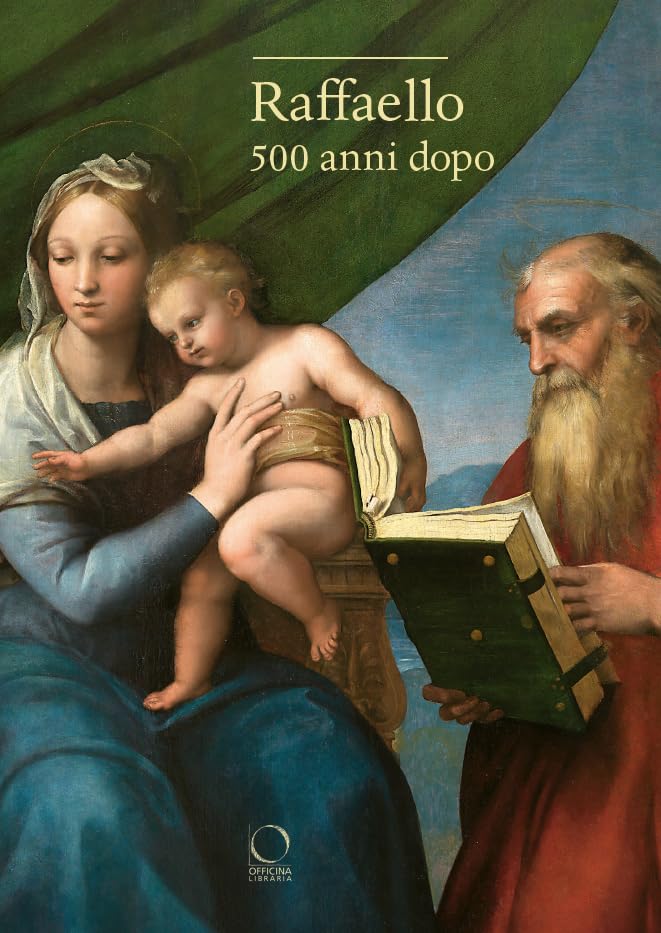

Il dipinto del giorno che vi propongo oggi è la Madonna della Rosa, realizzato a olio su tavola attorno al 1518 da Raffaello Sanzio e da due promettenti allievi della sua bottega: Giulio Romano e Giovan Francesco Penni.

L’opera deve il suo nome alla rosa dipinta in primo piano, evidente simbolo mariano che fa riferimento sia al Paradiso che alla purezza della Vergine.

La composizione presenta un momento intimo e privato tra la Madonna e il Figlio assieme a San Giuseppe e a San Giovannino Battista, patrono di Firenze, che Gli porge il cartiglio con la scritta Agnus Dei.

La Madonna mostra un volto sereno ed è panneggiata in un mantello blu oltremare: con un gesto protettivo stringe a sé il Figlio mentre Lui completamente nudo ha una posa dinamica e sembra volersi divincolare dalla stretta della madre per raggiungere Giovannino.

Lo slancio del Bambino verso il cugino è la figurata accettazione della Passione a cui è stato destinato prima ancora di essere concepito dalla Madre delle madri.

Attribuzione e datazione

L’opera è Raffaello ma sono stati evidenziati gli interventi dei suoi allievi, in particolare di Giulio Romano nella realizzazione di alcune figure secondarie e del paesaggio.

La datazione al 1518 circa si basa su elementi stilistici e su alcuni documenti storici. Inizialmente conservata presso il monastero dell’Escorial, l’opera è stata poi trasferita al Museo del Prado nel 1839 dove tutt’oggi può essere ammirata

Un capolavoro del Rinascimento

La Madonna della Rosa rappresenta un esempio emblematico della pittura rinascimentale di Raffaello on una composizione armoniosa, l’uso sapiente della luce e dei colori, la resa naturalistica delle figure e la profondità psicologica dei personaggi.

Oltre al suo valore artistico, la Madonna della Rosa riveste un’importanza notevole per la sua storia e per le testimonianze che offre sulla tecnica pittorica di Raffaello e della sua bottega.

Alcuni studiosi ipotizzano che la figura di San Giovannino Battista sia un ritratto di Giovan Francesco Penni, uno dei collaboratori di Raffaello.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

Raphael’s Madonna of the Rose: Historical Influences and Curiosities

The painting of the day that I propose to you today is the Madonna of the Rose, created in oil on panel around 1518 by Raffaello Sanzio and two promising students of his workshop: Giulio Romano and Giovan Francesco Penni.

The work owes its name to the rose painted in the foreground, a clear Marian symbol that refers both to Paradise and to the purity of the Virgin.

The composition presents an intimate and private moment between the Madonna and her Son together with Saint Joseph and Saint John the Baptist, patron saint of Florence, who hands him the scroll with the writing Agnus Dei.

The Madonna shows a serene face and is draped in an ultramarine blue cloak: with a protective gesture she holds her Son close to her while he, completely naked, has a dynamic pose and seems to want to free himself from his mother’s grasp to reach Giovannino.

The Child’s impulse towards his cousin is the figurative acceptance of the Passion to which he was destined even before being conceived by the Mother of mothers.

Attribution and dating

The work is Raphael but the interventions of his students were highlighted, in particular Giulio Romano in the creation of some secondary figures and the landscape.

The dating to around 1518 is based on stylistic elements and some historical documents. Initially preserved at the Escorial monastery, the work was then transferred to the Prado Museum in 1839 where it can still be admired today

A Renaissance masterpiece

The Madonna of the Rose represents an emblematic example of Raphael’s Renaissance painting with a harmonious composition, the skilful use of light and colours, the naturalistic rendering of the figures and the psychological depth of the characters.

In addition to its artistic value, the Madonna of the Rose is of notable importance for its history and for the evidence it offers on the pictorial technique of Raphael and his workshop.

Some scholars hypothesize that the figure of Saint John the Baptist is a portrait of Giovan Francesco Penni, one of Raphael’s collaborators.

For the moment, your always Michelangelo Buonarroti greets you and will meet you in the next posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €

-

Pasqua nell’arte: 7 capolavori che raccontano la resurrezione tra luce, dramma e speranza

🇮🇹La Pasqua raccontata dai grandi artisti. Dal Rinascimento al Novecento, la resurrezione ha ispirato capolavori straordinari: ecco 7 opere che trasformano luce, dramma e speranza in immagini indimenticabili… Easter as told by great artists. From the Renaissance to the twentieth century, the resurrection has inspired extraordinary masterpieces: here are 7 works that transform light, drama,…

-

Il mondo di Monet prende vita sul palco: la nuova tournée teatrale che celebra il maestro della luce

🇮🇹Debutta nel 2026 lo spettacolo teatrale “Monet. Una vita a colori” di Marco Goldin: un viaggio immersivo tra arte, musica e immagini per celebrare i 100 anni dalla morte di Claude Monet… 🇬🇧Marco Goldin’s theatrical production “Monet. A Life in Color” will debut in 2026: an immersive journey through art, music, and images to celebrate…

-

Donatello al Museo: visite guidate ai capolavori del Rinascimento al Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Firenze

Dal 14 marzo 2026 l’Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore inaugura una nuova esperienza dedicata agli amanti dell’arte: un ciclo di visite guidate alla scoperta dei capolavori di Donatello conservati nel Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Firenze…