Il Giudizio Universale: l’affresco che cambiò l’arte

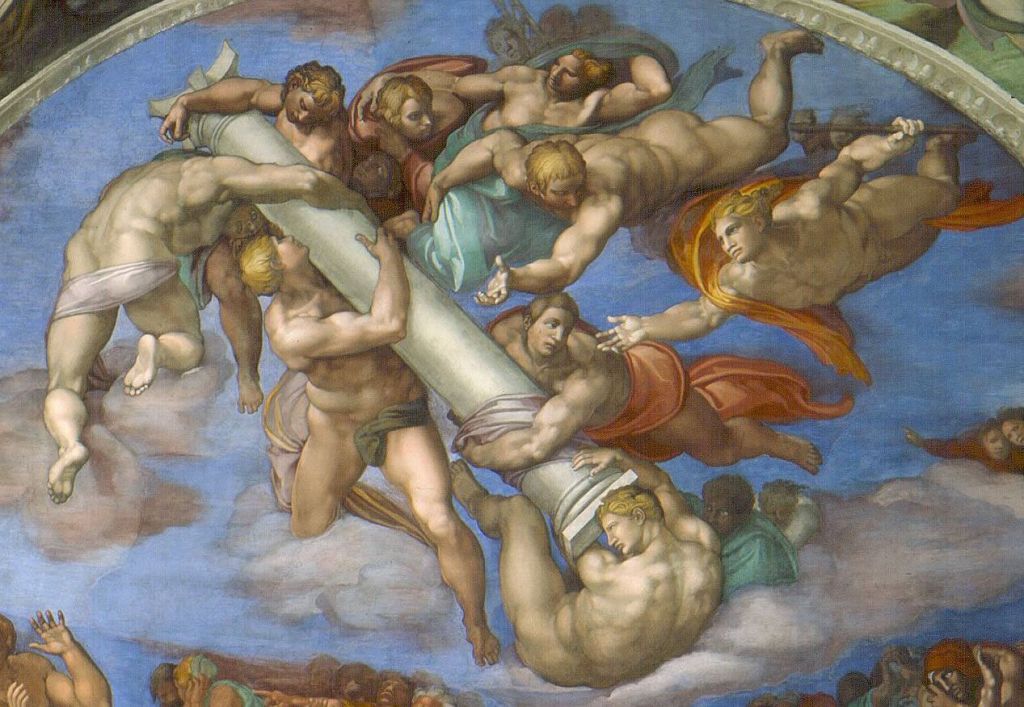

Il Giudizio Universale che affrescai sulla parete d’altare della Cappella Sistina, è una delle opere più note e, permettetemi di mettere da parte la falsa modestia, più sconvolgenti della storia dell’arte.

Un lavoro enorme, faticoso e totalizzante, che mi tenne inchiodato a sé per cinque anni buoni, dal 1536 al 1541.

Già avevo oltrepassato la soglia dei sessant’anni e l’età sul groppone mi pesava tutta. Affrontai quell’impegno con la consapevolezza della maturità trasformando quella parete in un capolavoro che tutt’oggi, ai vostri tempi, viene apprezzato e studiato come tale.

La commissione del Papa e i miei dubbi

Nel 1533, Papa Clemente VII affidò a me l’incarico di affrescare il Giudizio Universale sotto la volta della Sistina che avevo ultimato di affrescare 37 anni prima. A dire il vero non accolsi quella proposta con grande entusiasmo. Ero ben conscio di quanto l’affresco fosse fisicamente faticoso e impegnativo a livello mentale.

La parete era di grandi dimensioni e io non avevo più trent’anni.

La realizzazione del nuovo affresco avrebbe comportato modifiche architettoniche importanti, come la chiusura di alcune finestre e la possibile distruzione di decorazioni precedenti anche se in un primo momento avevo pensato di inglobare nella nuova opera sia i due affreschi nella seconda fascia del Perugino che la pala d’altare realizzata sempre da lui.

Papa Clemente VII de’ Medici voleva lasciare il suo nome nella Sistina come aveva fatto il predecessore della sua stessa casata Leone X de’ Medici commissionando gli arazzi a Raffaello.

In un primo momento, il progetto prevedeva la realizzazione non del Giudizio ma della Caduta degli Angeli Ribelli, ma questa idea venne presto abbandonata.

Quei Giudizi Universali che già conoscevo

Il Giudizio Universale non era un soggetto nuovo per me. A Firenze avevo avuto modo di vedere celebri rappresentazioni del tema, come l’affresco di Orcagna in Santa Croce, e conosceva bene le opere di artisti come Luca Signorelli, autore del potente ciclo apocalittico nel Duomo di Orvieto. Chissà se lo vidi mai di persona ma certo è che perlomeno avevo avuto modo di avere tra le mani qualche riproduzione dell’opera del Signorelli.

Le riflessioni sulla morte, sul destino dell’anima e sulla salvezza mi portarono a immaginare un Giudizio Universale mai visto prima che però molto aveva a che fare con l’Inferno di Dante che tanto amavo.

Affresco potente, drammatico e rivoluzionario

Il Giudizio Universale stupì e sconvolse i miei contemporanei per la sua forza visiva. Le figure nude, muscolose, in continuo movimento, travolte dal dramma del giudizio divino non rispettano un ordine rigido: preferii disporle come fosse una sorta di vortice di corpi ma anche di emozioni contrastanti.

Questa visione risultò sconvolgente e controversa. Molte delle novità iconografiche introdotte dall’artista suscitarono critiche e polemiche, ma contribuirono a rendere l’opera unica e rivoluzionaria.

Dalla morte di Clemente VII a Paolo III

Alla morte di Clemente VII, nel 1534, sperai quasi che quella commissione venisse sciolta per poter proseguire a lavorare alla tomba di Giulio II che da anni mi tormentava.

In nuovo papa, Paolo III Farnese, volle invece fortemente farmi portare avanti il progetto e non potevo certo dire di no.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

The Last Judgement: The Fresco That Changed Art

The Last Judgement, which I frescoed on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, is one of the most famous and—allow me to set aside false modesty—most shocking works in the history of art. It was an enormous, laborious, and all-encompassing undertaking, which engrossed me for a full five years, from 1536 to 1541.

I was already in my sixties, and age was weighing heavily on me. I approached that task with the awareness of maturity, transforming that wall into a masterpiece that even today, in your time, is appreciated and studied as such.

The Pope’s Commission and My Doubts

In 1533, Pope Clement VII entrusted me with the task of frescoing the Last Judgement under the Sistine Chapel vault, which I had completed 37 years earlier. To be honest, I wasn’t very enthusiastic about the proposal. I was well aware of how physically demanding and mentally demanding the fresco would be.

The wall was large, and I was no longer thirty.

The creation of the new fresco would have entailed significant architectural changes, such as closing some windows and possibly destroying previous decorations. I had initially considered incorporating both Perugino’s two frescoes in the second section and his altarpiece into the new work.

Pope Clement VII de’ Medici wanted to leave his name in the Sistine Chapel, as his predecessor, Leo X de’ Medici, had done by commissioning the tapestries from Raphael.

At first, the project called for the Fall of the Rebel Angels rather than the Last Judgment, but this idea was soon abandoned.

Those Last Judgments I already knew

The Last Judgment was not a new subject for me. In Florence, I had seen famous depictions of the theme, such as Orcagna’s fresco in Santa Croce, and I was well acquainted with the works of artists like Luca Signorelli, author of the powerful apocalyptic cycle in the Orvieto Cathedral. Who knows if I ever saw it in person, but I certainly had at least had my hands on some reproductions of Signorelli’s work.

Reflections on death, the fate of the soul, and salvation led me to imagine a Last Judgment never seen before, yet one that had much in common with Dante’s Inferno, which I loved so much.

A Powerful, Dramatic, and Revolutionary Fresco

The Last Judgment astonished and shocked my contemporaries with its visual power. The nude, muscular figures, in constant motion, swept up in the drama of divine judgment, do not adhere to a rigid order: I preferred to arrange them as if they were a sort of vortex of bodies but also of contrasting emotions.

This vision was shocking and controversial. Many of the artist’s iconographic innovations sparked criticism and controversy, but they helped make the work unique and revolutionary.

From the Death of Clement VII to Paul III

Upon the death of Clement VII in 1534, I almost hoped that the commission would be dissolved so I could continue working on the tomb of Julius II, which had tormented me for years.

The new pope, Paul III Farnese, however, strongly urged me to continue the project, and I certainly couldn’t say no.

For now, yours truly, Michelangelo Buonarroti bids you farewell and invites you to see him in future posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €