San Pietro: la perfezione anatomica

La descrizione del corpo mi veniva quasi naturale. Quasi.

L’anatomia la conoscevo bene e l’avevo studiata fin da ragazzino sui corpi, analizzandone come fossi uno scienziato ogni rilievo e avvallamento, ogni tendine e vena. A menadito sapevo cosa accade alla muscolatura quando un arto si piega, quando il busto è sottoposto a uno sforzo e altre mille peculiarità che puntualmente, riportavo nelle opere mie.

Doverosa e necessaria questa premessa prima di parlarvi di un corpo, quello di San Pietro.

Orbene, iniziai a metter mano all’ultimo affresco che avrei realizzato nel corso della mia vita nel 1545, quando già avevo compiuto settant’anni.

Mi ritrovai così a dover lavorare ancora una volta mettendo a dura prova corpo e mente. Elaborare un affresco simile non fu uno scherzo, sia dal punto di vista dell’impegno per studiare una composizione che mi soddisfacesse, sia dal punto di vista fisico.

L’affresco è faticoso, c’è poco da fare: richiede un’energia che poco si addice a un settantenne, soprattutto ai miei tempi quando a quell’età non erano in molto ad arrivarci.

Era stato papa Paolo III Farnese a commissionarmi quel lavoro, assieme alla Conversione di Saulo, dopo che avevo terminato di lavorare al Giudizio Universale per la Sistina. Voleva che la sua cappella del Palazzo Apostolico, progettata da Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane tra il 1537 e il 1539, divenisse il suo splendido oratorio privato ma anche un’aula dove poter ospitare i conclavi.

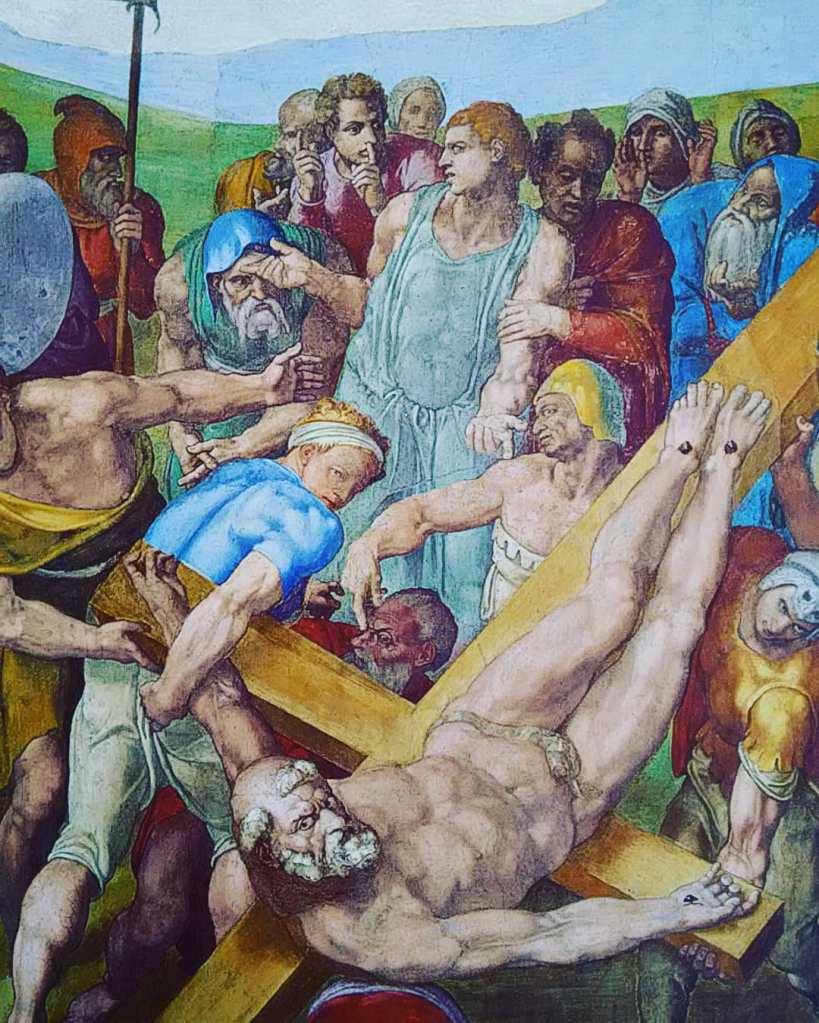

San Pietro guarda e ammonisce allo stesso tempo lo spettatore mentre il gruppo degli armigeri sta issando la croce a testa in giù, come lui stesso volle che fosse collocata. Dipinsi il corpo senza chiodi né perizoma, facendolo muovere con una torsione che contorce in direzioni opposte le gambe e il torso.

Il Santo compie uno sforzo nel tentativo di sollevare il busto e i muscoli della pancia si contraggono di conseguenza.

Osservando l’opera si ha l’impressione di essere dinanzi a un trattato di anatomia perfetto, con il muscolo retto ben identificabile e la linea alba.

La posizione di San Pietro è ben bilanciata, con i quadricipiti femorali ruotati verso destra alla ricerca dell’equilibrio di tutto il corpo.

Come vi ho accennato prima, anche in questo caso volli mostrare l’apostolo senza celare nulla. In fondo la sua carne fu testimonianza della sua fede e non esitò a sacrificarsi per mostrare il valore del suo credo.

Il perizoma fu aggiunto successivamente ed è evidente sia per la qualità della pittura realizzata per altro a secco sopra l’affresco, sia perché esistono disegni di San Pietro realizzati prima che venisse censurato come quelli di Lelio Orsi, realizzati tra il 1554 e il 1555.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

St. Peter: Anatomical Perfection

The description of the body came almost naturally to me. Almost. I knew anatomy well and had studied it since I was a boy on bodies, analyzing every relief and depression, every tendon and vein as if I were a scientist. I knew by heart what happens to the muscles when a limb bends, when the torso is subjected to stress and a thousand other peculiarities that I punctually reported in my works.

This premise is dutiful and necessary before talking to you about a body, that of Saint Peter.

Well, I began to work on the last fresco that I would create in the course of my life in 1545, when I had already turned seventy.

I thus found myself having to work once again, putting my body and mind to the test. Elaborating a fresco like that was no joke, both from the point of view of the commitment to study a composition that satisfied me, and from the physical point of view. The fresco is tiring, there is little to do: it requires an energy that is not suited to a seventy-year-old, especially in my time when at that age not many people could get there.

It was Pope Paul III Farnese who commissioned that work, together with the Conversion of Saul, after I had finished working on the Last Judgement for the Sistine Chapel. He wanted his chapel in the Apostolic Palace, designed by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger between 1537 and 1539, to become his splendid private oratory but also a hall where he could host conclaves.

Saint Peter watches and admonishes the viewer at the same time while the group of men-at-arms is hoisting the cross upside down, as he himself wanted it to be placed. The entire body that I painted without nails or loincloth is affected by a torsion that moves the legs and torso in opposite directions.

The Saint makes an effort in an attempt to lift his torso and the muscles of his stomach contract accordingly. Looking at the work you have the impression of being in front of a perfect anatomy treatise, with the rectus muscle clearly identifiable and the line alba.

The position of Saint Peter is perfectly balanced with the quadriceps femoris rotated to the right in search of balance of the whole body.

As I mentioned before, also in this case I wanted to show the whole body of the apostle. The loincloth was added later and it is evident both for the quality of the painting made, moreover, a secco over the fresco and because there are drawings of Saint Peter made before he was censored like those of Lelio Orsi, made between 1554 and 1555.

For the moment, the always your Michelangelo Buonarroti bids you farewell, making an appointment with you in the next posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €