Il disegno che modificai per amore

“Se questo schizzo non vi piace, ditelo a Urbino, acciò che io abbi tempo d’averne facto un altro doman da sera(…); e se vi piace e vogliate che io lo finisca, rimandatemelo”

Così scrissi al mio amato Tommaso de’ Cavalieri a margine del disegno per lui che aveva come tema la Caduta di Fetonte, oggi custodito al British Museum di Londra.

Narra Ovidio nelle Metamorfosi che Fetonte, il figliolo di Apollo, chiese al padre di poter guidare per un giorno il carro del Sole. Voleva mostrare tutto il suo coraggio e la sua nascita divina a Epafo che lo sbeffeggiava.

La poca esperienza del ragazzo però lo portò presto al disastro. Il giovane Fetonte non fu in grado di governare la quadriga che, fuori controllo, andò prima troppo in alto causando ondate di gelo sulla terra e poi si avvicinò troppo prosciugando fiumi, incendiando foreste e creando il deserto della Libia.

Giove, inorridito da quanto stava accadento, scagliò un fulmine contro il carro provocandone la caduta e la morte di Fetonte annegato nel fiume Eridano.

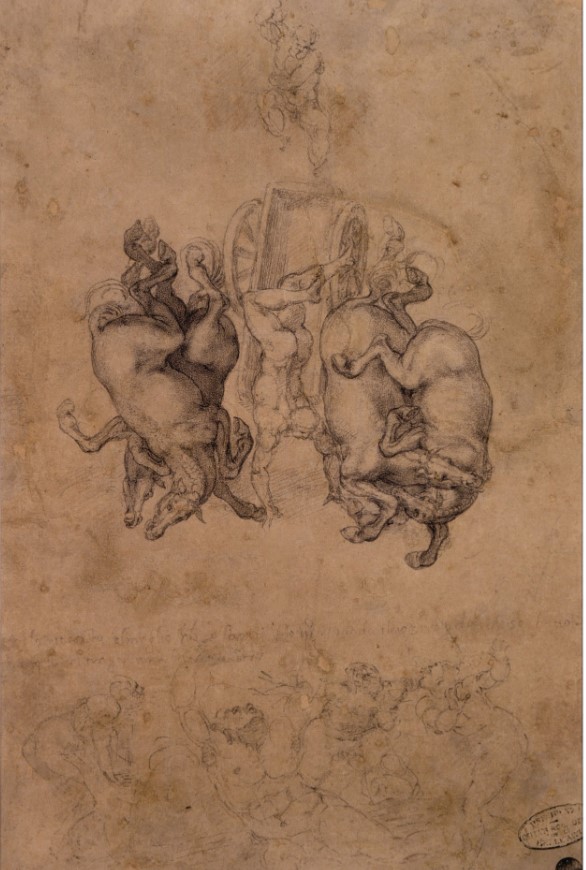

Per Tommaso volli disegnare proprio la scena della caduta del giovane figlio di Apollo mentre più in basso, le sue sorelle Eliadi, vedendo la scena che si sviluppa dinanzi ai loro occhi, si disperano trasformandosi in pioppi.

Giove, in posizione frontale, scaglia un fulmine contro il superbo Fetonte. Il giovane precipita assieme al cocchio con i cavalli. In basso si vedono il fiume Eridano, Cignus e tre Eliadi piangenti.

Desideravo talmente tanto che Tommaso avesse qualcosa di mio che avrei finanche cambiato il disegno a suo gusto pur di fargli piacere.

Per chi altro avrei fatto qualcosa di simile?

In effetti di questo foglio esistono tre versioni: la prima del British Museum, la seconda custodita presso la collezione del Gabinetto disegni e stampe delle Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia e quella che viene considerata la versione definitiva, appartenente oggi al Castello di Windsor.

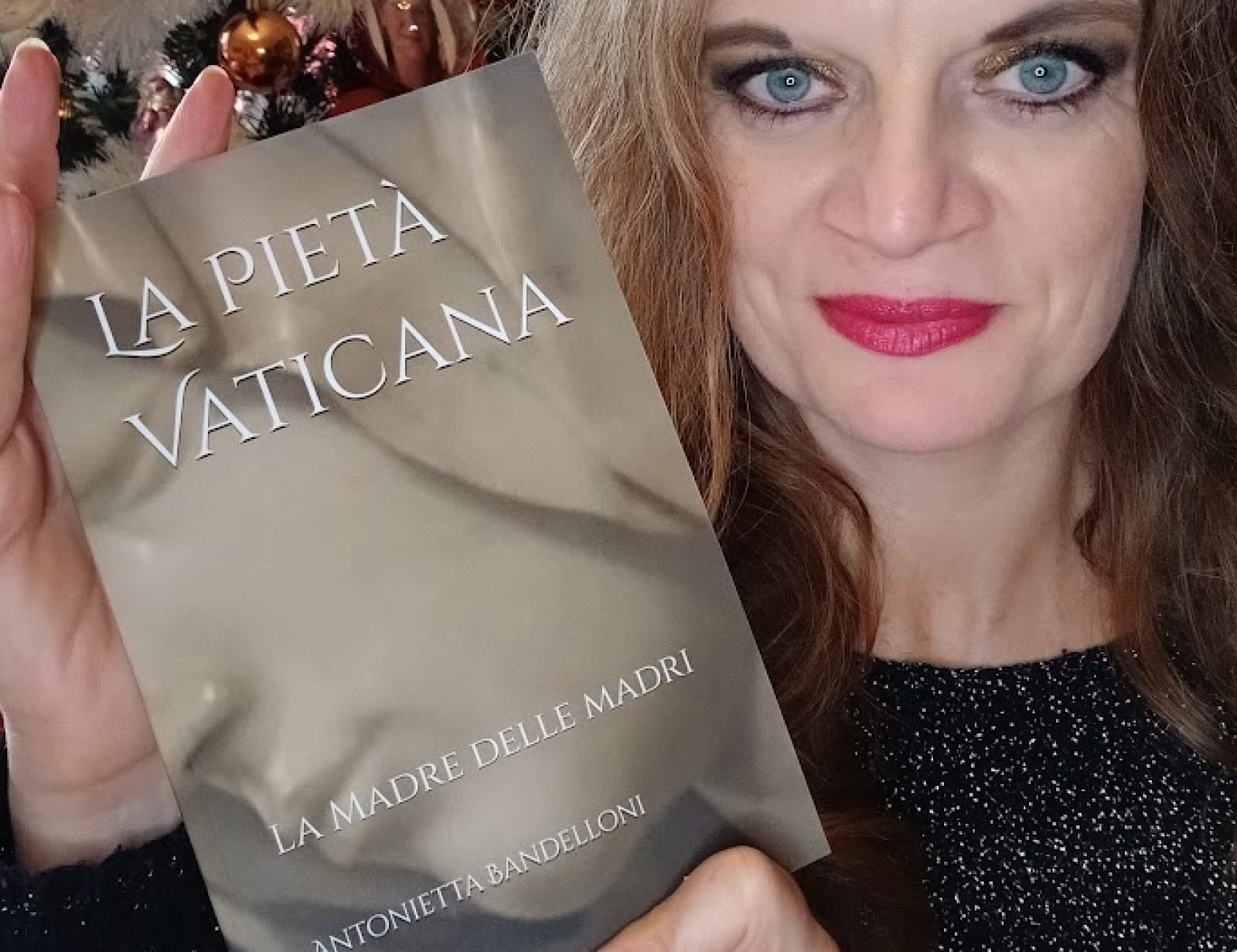

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

The drawing I modified out of love

“If you don’t like this sketch, tell Urbino, so that I have time to make another one tomorrow evening (…); and if you like it and want me to finish it, send it back to me.”

So I wrote to my beloved Tommaso de’ Cavalieri in the margin of the drawing for him which had as its theme the Fall of Phaeton, now kept in the British Museum in London.

Ovid narrates in the Metamorphoses that Phaeton, the son of Apollo, asked his father to be able to drive the chariot of the Sun for a day. He wanted to show all his courage and his divine birth to Epaphos who mocked him.

However, the boy’s lack of experience soon led to disaster. The young Phaeton was unable to govern the quadriga which, out of control, first went too high causing waves of frost on the earth and then came too close, drying up rivers, setting forests on fire and creating the Libyan desert.

Jupiter, horrified by what was happening, hurled a bolt of lightning at the chariot, causing it to fall and the death of Phaethon, who drowned in the Eridanus river.

For Thomas I wanted to draw the scene of the fall of the young son of Apollo while further down, his Eliade sisters, seeing the scene unfolding before their eyes, despair and transform into poplar trees.

Jupiter, in a frontal position, hurls a thunderbolt at the proud Phaeton. The young man falls together with the chariot with the horses. Below you can see the river Eridanos, Cignus and three weeping Heliades.

I wanted Tommaso to have something of mine so much that I would even change his design to suit his taste just to please him.

Who else would I have done something similar for?

In fact, there are three versions of this sheet: the first in the British Museum, the second kept in the collection of the Cabinet of Drawings and Prints of the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and the one that is considered the definitive version, today belonging to Windsor Castle.

For the moment, your always Michelangelo Buonarroti greets you and will meet you in the next posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €

-

Il gesto intimo della Donna che si allaccia i sandali di Rudolph Schadow

🇮🇹Scolpendo la donna che si allaccia i Sandali, Rudolph Schadow sceglie il quotidiano al posto del mito, trasformando un gesto intimo in un’opera d’arte. Un marmo silenzioso, concentrato, sorprendentemente moderno… 🇬🇧By sculpting the woman tying her sandals, Rudolph Schadow chooses the everyday over the mythical, transforming an intimate gesture into a work of art. A…

-

Velarìa: i grandi velieri trasformano La Spezia in un museo galleggiante del Mediterraneo

🇮🇹Vele, legni antichi, rotte di bellezza. A marzo La Spezia si trasforma in un museo galleggiante: arrivano i grandi velieri e le golette del Mediterraneo. Nasce Velarìa – Scalo alla Spezia, il nuovo Festival Marittimo Internazionale… 🇬🇧Sails, ancient woods, routes of beauty. In March, La Spezia transforms into a floating museum: the great sailing ships…

-

Alchimia Ginori: due secoli di arte, tecnica e sperimentazione in mostra al MIC Faenza

🇮🇹 Quando la porcellana diventa alchimia. Dal 31 gennaio 2026 al MIC Faenza apre Alchimia Ginori 1737–1896, una mostra che racconta due secoli di arte, chimica e sperimentazione della Manifattura Ginori… 🇬🇧 When porcelain becomes alchemy. From January 31, 2026, MIC Faenza will host Alchimia Ginori 1737–1896, an exhibition recounting two centuries of art, chemistry,…