Intervista alla miniatrice Marie Lefèvre

Nel cuore di una tradizione antica fatta di oro in foglia, pigmenti macinati a mano e pazienza monastica, Marie Lefèvre ha scelto di dare nuova vita all’antica arte della miniatura.

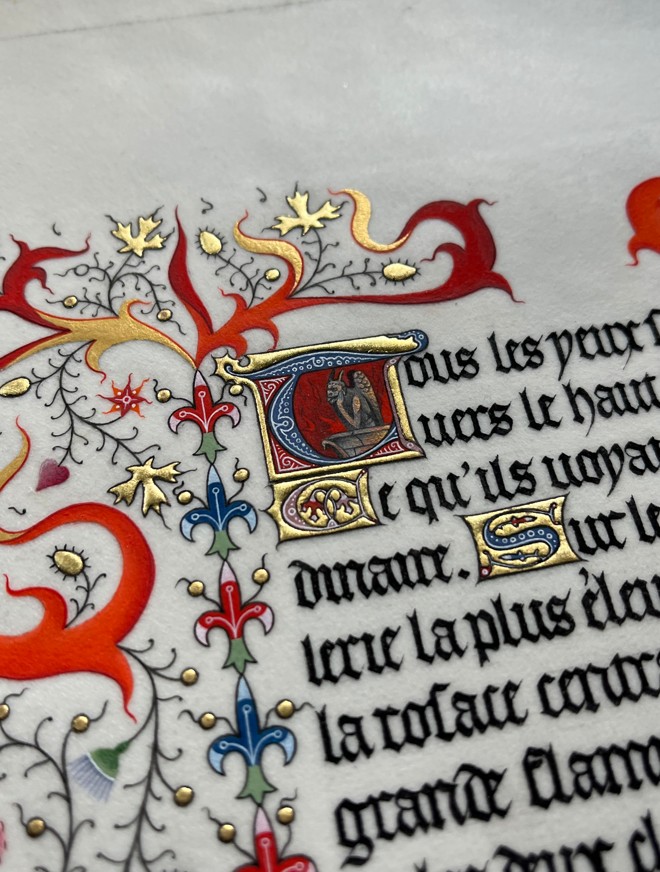

Nel suo straordinario laboratorio Expecto Pigmentum, ogni miniatura è frutto di un perfetto equilibrio tra rigore storico e sensibilità contemporanea. Fogli manoscritti attingendo dall’eredità medievale prendono vita giorno dopo giorno sotto le pazienti mani di Marie Lefèvre, che da ogni cosa che la circonda trae ispirazione per dar forma a miniature sorprendenti.

Ho avuto il piacere e l’onore di intervistare Marie Lefèvre per chiederle un po’ di più riguardo al suo preziosissimo lavoro.

- Quali sono le principali sfide tecniche che incontri nella creazione di magnifiche miniature?

“La miniatura è una forma d’arte articolata in una successione di fasi, svolta nel Medioevo da persone diverse: gli scriptoria e le botteghe impiegavano scrivani, che si occupavano della calligrafia, doratori, disegnatori e miniatori, ognuno con il proprio compito.

Oggi svolgo personalmente tutte queste fasi e questo richiede la padronanza di diverse tecniche: la preparazione dei pigmenti, la calligrafia, l’applicazione della foglia d’oro e, naturalmente, le tecniche pittoriche, che variano a seconda del periodo e dello stile della miniatura.

L’unica difficoltà tecnica che a volte incontro nella creazione di una miniatura è la fase di applicazione della foglia d’oro al gesso. Il gesso è un rivestimento a base di colla di pesce, zucchero e pigmento bianco che a volte può essere instabile, a seconda della temperatura e dell’umidità ambientale.

Può causare difficoltà durante l’applicazione se è molto caldo e secco e asciuga troppo velocemente, ma anche durante l’applicazione della foglia d’oro se non aderisce sufficientemente bene, e anche successivamente, durante la fase di brunitura con una pietra d’agata lucida montata su un manico. Lo scopo di questa brunitura è rendere l’oro più liscio e brillante mediante lo strofinamento.

- Lavori ancora con la pergamena come nel XIV e XV secolo, o preferisci la carta moderna?

“Lavoro su pergamena; è un supporto che ho scoperto quando ho iniziato a miniare e che continua a stupirmi. La pergamena ha un vantaggio che manca alla carta per la miniatura: essendo fatta di pelle animale, è impermeabile, permettendo al colore di essere semplicemente applicato sopra e di esprimere appieno la luce dei pigmenti.

La carta, d’altra parte, assorbe il colore e lo rende più opaco, meno luminoso. Ho provato la miniatura su carta alcune volte, ma preferisco di gran lunga lavorare su pergamena. Per me, è parte integrante di ciò che una miniatura rappresenta ed è un materiale che richiede un know-how che deve essere preservato!

- Consulta a volte codici originali in archivi o biblioteche?

“Ho già avuto modo di consultare manoscritti risalenti all’VIII, XI, XIV e XVI secolo presso la Biblioteca Nazionale di Francia e la Bibliothèque d’Angers. Osservare manoscritti d’epoca offre diversi vantaggi: come miniatore, permette di comprendere le tecniche pittoriche e di notare dettagli non visibili nelle digitalizzazioni disponibili online, anche quando sono di altissima qualità.

Si può quindi capire come il miniatore dipingeva, quali pigmenti ha usato, analizzare l’ordine in cui ha lavorato e vedere con i propri occhi ogni singola pennellata. È molto arricchente potersi dedicare a questo esercizio, anche molto stimolante, e ci sono ancora così tanti manoscritti che vorrei consultare, alla BnF ovviamente, ma anche in altre biblioteche perché i tesori sono ovunque!”

- Ci sono maestri miniatori del passato che ammiri particolarmente e che ti ispirano?

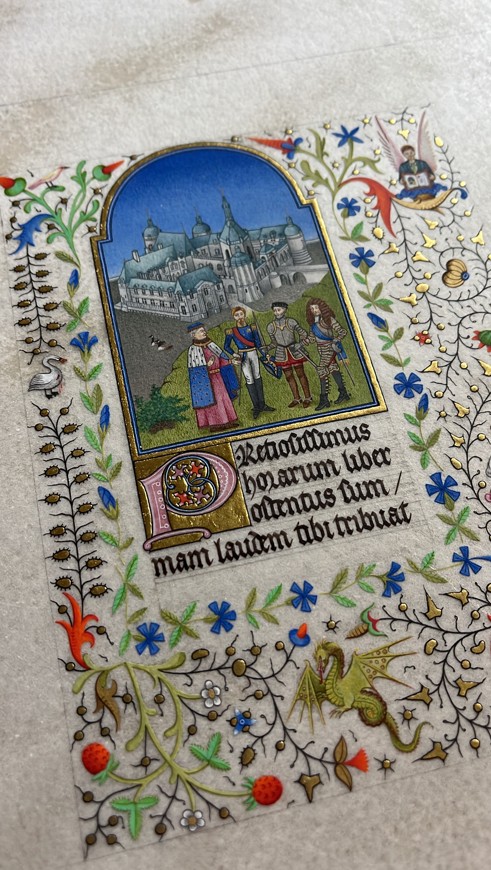

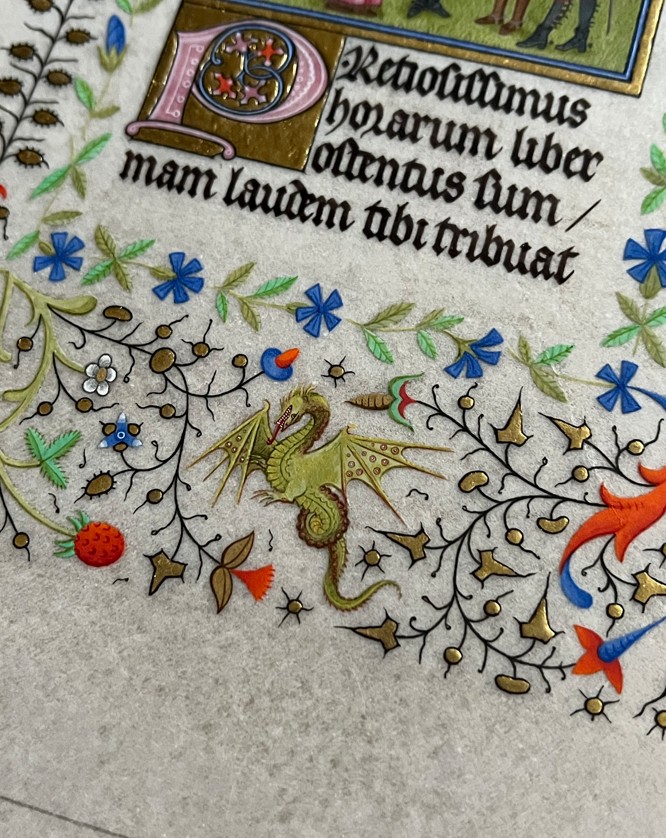

Avendo avuto l’opportunità di visitare tre volte la mostra sulle Très Riches Heures del Duca di Berry al Castello di Chantilly qualche mese fa, non posso non parlare dello straordinario lavoro di disegno e miniatura dei fratelli Limbourg, per i quali nutro un’ammirazione sconfinata!

Ammiro molto anche il lavoro di rinomati miniatori come il Maestro della Città delle Dame, il Maestro di Boucicaut e il Maestro Honoré, solo per citarne alcuni.

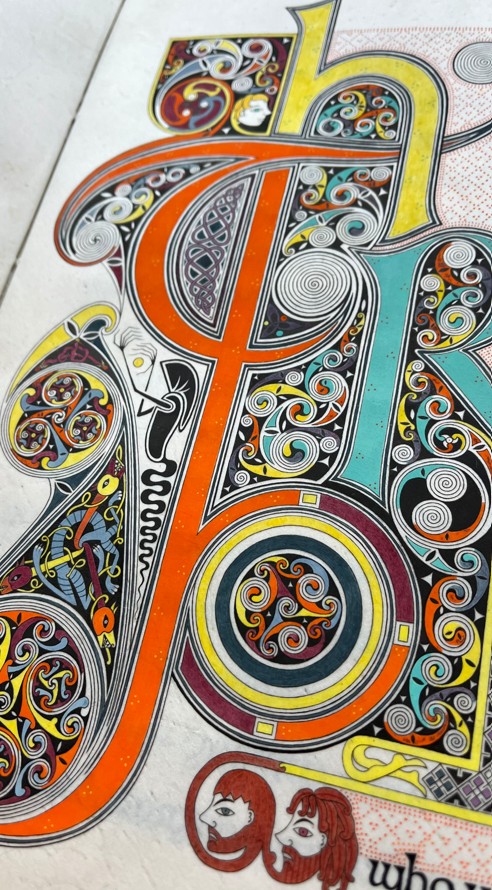

Vedere manoscritti miniati da donne – perché nel Medioevo esistevano ed erano più numerose di quanto si possa immaginare – mi commuove in modo particolare. Penso, ad esempio, a Jeanne de Montbaston, che miniò il famoso “Romanzo della Rosa” alla fine del XIV secolo. Penso anche a tutti i miniatori anonimi che hanno dedicato la loro vita alla copia e all’ornamentazione dei manoscritti, come, tra i tanti, i monaci che copiarono e miniarono durante l’VIII secolo il Libro di Kells, uno dei manoscritti più preziosi al mondo e tra i miei preferiti, che testimonia un’abilità, uno stile e una storia inestimabili.

- Esistono materiali antichi difficili da reperire o che non possono più essere utilizzati oggi?

Tornando alla pergamena, oggi è un materiale raro, difficile da reperire, soprattutto per la qualità della pergamena presente nei manoscritti medievali, che è molto fine e molto morbida, sia sul lato venato (superficie esterna) che sul lato carne (superficie interna).

Tra i materiali difficili da reperire ci sono i pigmenti vegetali in generale, come il verde linfa e il folium. Il bianco di piombo è un altro esempio è un pigmento difficile da trovare perché la sua vendita è vietata in modo permanente in Francia e in Europa.

- Quanto tempo impieghi in media per creare una pagina miniata?

È difficile stimarlo, poiché tutto dipende dallo stile di miniatura. Alcuni stili, come il cosiddetto stile “Insulare” (lo stile dei manoscritti miniati in Irlanda e Gran Bretagna tra il VI e l’inizio del IX secolo), ad esempio, richiedono più tempo di altri.

Il tempo impiegato per una pagina dipende anche dalle sue dimensioni e dalla quantità di dettagli da dipingere! Il mio manoscritto miniato a doppia pagina raffigurante l’incendio di Notre-Dame, che misura 60 cm di larghezza e 38 cm di altezza, mi ha richiesto 550 ore di lavoro, tra ricerca, disegno, calligrafia, doratura e pittura. Per fare un altro esempio, una pagina più piccola che ho creato di recente, raffigurante il Castello di Chantilly, mi ha richiesto 96 ore di doratura e pittura.

- In che modo il ritmo lento e meditativo del tuo lavoro influenza la tua creatività?

“È una domanda molto interessante! Quando inizio a lavorare su un manoscritto miniato, inizio con la ricerca, che è di per sé un viaggio nel tempo, poiché consulto versioni digitalizzate di numerosi manoscritti per trovare dettagli, impaginazioni e motivi che mi ispirano.

Poi arriva il disegno, che mi permette di selezionare ciò che ha catturato la mia attenzione durante la ricerca. Questo è un importante processo preparatorio durante il quale mi ritiro in me stesso per organizzare la composizione, posizionare i dettagli e dare forma concreta all’idea che ho in mente.

Quando arriva il momento di applicare la foglia d’oro, di dipingere, di calligrafare, inizia un vero e proprio viaggio interiore e persino spirituale, che si estende per giorni, settimane, a volte mesi, e continua anche quando non ho il pennello in mano, chino sulla pergamena.

Spesso sogno l’illuminazione di notte, vedendo motivi floreali, spirali e intrecci nei miei sogni. L’ispirazione è ovunque, anche quando ogni giorno faccio una passeggiata nella natura e vedo uno scoiattolo su un albero, il disegno della brina su una foglia in inverno, i colori di un’alba…

Ogni colore applicato alla pergamena, ogni pennellata, è una tappa di questo viaggio interiore, perché durante tutte queste ore mi ritrovo solo con la mia opera, e questo mi permette di riflettere profondamente, di meditare, di districare i miei pensieri e di forgiare dall’interno ciò che desidero trasmettere attraverso l’illuminazione su cui sto lavorando. Qualunque problema incontri nella vita, qualunque emozione mi attraversi durante il giorno, mi vedo sempre come un generatore di luce; trasformo tutto ciò che penso e sento in bellezza e luce, perché questo è esattamente ciò che significa “miniatore”: “illuminare/portare alla luce”. Con ogni manoscritto miniato che creo, dedico una parte della mia vita e affido una parte della mia anima, ed è questo che trovo più meraviglioso in quest’arte.

- Hai progetti futuri, magari un codice completo di tua creazione o una collaborazione con un museo di cui vorresti parlarci?

“Ho già completato un manoscritto di circa quindici pagine, in stile Insulare ispirato al Libro di Kells e sul tema di un racconto del mondo di Harry Potter, che mi ha richiesto un anno e mezzo di lavoro tra il 2019 e il 2021! Creare un altro codice intero è qualcosa che sogno molto e che mi piacerebbe poter realizzare un giorno, ma al momento non ho il tempo da dedicargli perché richiederebbe anni di lavoro!

Ho molti progetti personali che prevedono illustrazioni miniate a tutta pagina su vari soggetti che aspettano

di essere dipinti, e presto lavorerò per un museo, ma non posso ancora parlarne…!”

Grazie Marie per la tua disponibilità, gentilezza infinita e per portare avanti una meravigliosa tradizione con tanto amore, passione e competenza.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

Interview with illuminator Marie Lefèvre

At the heart of an age-old tradition of gold leaf, hand-ground pigments, and almost monastic patience, Marie Lefèvre has chosen to revive the ancient art of miniature painting.

In her extraordinary Expecto Pigmentum studio, each miniature is the result of a perfect balance between historical rigor and contemporary sensibility. Handwritten sheets, drawing their designs from the medieval heritage, come to life day after day under the expert hands of Marie Lefèvre, who finds inspiration in everything around her to create astonishing miniatures.

I had the pleasure and honor of speaking with Marie Lefèvre to learn more about her invaluable work.

- What are the main technical challenges you encounter in creating such magnificent miniatures?

Illumination is an art form organized into a series of steps, carried out in the Middle Ages by various individuals: scriptoria and workshops employed scribes, who handled the calligraphy, gilders, draftsmen, and illuminators, each with their specific task.

Today, I perform all these steps myself, which requires mastery of a variety of techniques: preparing the pigments, calligraphy, applying gold leaf, and, of course, the painting techniques that differ depending on the period and style of illumination. The only technical difficulty I sometimes encounter when creating an illuminated manuscript is applying gold leaf to gesso. Gesso is a coating made from fish glue, sugar, and white pigment, which can be temperamental depending on the ambient temperature and humidity. It can cause difficulties during application if it’s very hot and dry and dries too quickly, but also during the application of the gold leaf if it doesn’t adhere well enough, and even afterward, during the burnishing stage with a polished agate stone mounted on a handle. The purpose of this stone is to rub the gold leaf, making it smoother and shinier.

- Do you still work with parchment as in the 14th and 15th centuries, or do you prefer modern paper?

I work on parchment. It’s a support I discovered when I started illumination, and it never ceases to amaze me. Parchment has an advantage that paper doesn’t for illumination: being made from animal skin, it’s waterproof, allowing the paint to simply be applied to it and to fully express the light of the pigments. Paper, on the other hand, absorbs the paint, making it duller and less luminous. I’ve tried illumination on paper a few times, but I much prefer working on parchment. For me, it’s an integral part of what illumination represents, and it’s a material that requires a certain expertise that must be preserved!

- Do you ever consult original codices in archives or libraries?

I’ve already had the opportunity to consult manuscripts dating from the 8th, 11th, 14th, and 16th centuries at the National Library of France and the Angers Library. Observing period manuscripts has several advantages: as an illuminator, it allows you to understand the painting techniques and notice details that aren’t visible in the digitizations available online, even when they are of very high quality. You can therefore understand how the illuminator painted, what pigments they used, analyze the order in which they worked, and see every single stroke with your own eyes. It’s incredibly enriching to be able to participate in this exercise, and very inspiring as well. There are still so many manuscripts I’d love to consult, at the BnF of course, but also in other libraries, because treasures are everywhere!

Are there any master illuminators of the past whom you particularly admire and who inspire you?

Having had the opportunity to visit the exhibition on the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry at the Château de Chantilly three times a few months ago, I must mention the breathtaking drawing and illumination work of the Limbourg brothers, for whom I have boundless admiration!

I also greatly admire the work of renowned illuminators such as the Master of the City of Ladies, the Bouciaut Master, and Master Honoré, to name just a few.

Seeing manuscripts illuminated by women—for they did exist and were more numerous than one might imagine in the Middle Ages—particularly moves me. I think, for example, of Jeanne de Montbaston, who illuminated the famous “Romance of the Rose” at the end of the 14th century.

I also think of all the anonymous illuminators who dedicated their lives to copying and embellishing manuscripts, such as, among so many others, the monks who copied and illuminated the Book of Kells during the 8th century, one of the most precious manuscripts in the world and among my favorites, which testifies to a remarkable skill and artistry style and invaluable history.

- Are there any ancient materials that are difficult to find or that can no longer be used today?

To return to parchment, it is now a rare material, difficult to find, especially the quality of parchment found in medieval manuscripts, which is very fine and soft, both on the grain side (outer surface) and the flesh side (inner surface).

Among the materials that are difficult to obtain are pigments of plant origin in general, such as sap green and folium. Lead white is another example of a pigment that is difficult to find because it is permanently banned from sale in France and Europe.

- How long does it take you on average to create an illuminated page?

It’s difficult to estimate, as it all depends on the style of illumination. Some styles, like the so-called “Insular” style (the style of illuminated manuscripts in Ireland and Great Britain between the 6th and early 9th centuries), require more time to complete than others.

The time spent on a page also depends on its size and the amount of detail to be painted! My illuminated double-page spread depicting the fire at Notre-Dame, which measures 60 cm wide and 38 cm high, took me 550 hours of work, including research, drawing, calligraphy, gilding, and painting. To give another example, a smaller page I recently completed, featuring the Château de Chantilly, took me 96 hours of gilding and painting.

- How does the slow, meditative pace of your work influence your creativity?

That’s a very interesting question! When I begin working on an illuminated manuscript, I start with research, which is in itself a journey through time, as I consult digitized versions of numerous manuscripts to find details, layouts, and motifs that inspire me. Next comes the drawing stage, which allows me to select what has caught my attention during my research. This is an important preparatory process for which I withdraw into myself to organize the composition, place the details, and give concrete form to the idea I have in my mind.

Once the time comes to apply the gold leaf, to paint, to calligraph, a true inner and even spiritual journey begins, one that extends over days, weeks, sometimes months, and continues even when I don’t have the brush in my hand, bent over my parchment. I often dream of illuminated manuscripts at night, seeing motifs of flowers, spirals, and interlacing patterns in my dreams. Inspiration is everywhere, even when I go for a walk in nature each day and see a squirrel in a tree, the pattern of frost on a leaf in winter, the colors of a sunrise…

Each color applied to the parchment, each brushstroke, is a step on this inner journey, because during all those hours, I find myself alone with my work, and this allows me to reflect deeply, to meditate, to untangle my thoughts, and to forge from within what I wish to convey through the illumination I am working on. Whatever problems I encounter in life, whatever emotions may pass through me during the day, I always see myself as a generator of light. I transform everything I think and feel into beauty and light, because that is precisely what “illuminator” means: “to illuminate/to bring to light.” With each illumination I create, I dedicate a part of my existence and entrust a part of my soul, and that is what I find most wonderful about this art.

- Do you have any future projects, perhaps a complete codex of your own creation or a collaboration with a museum you’d like to tell us about?

I’ve already completed a fifteen-page manuscript in an Insular style inspired by the Book of Kells, based on a story from the Harry Potter universe. It took me a year and a half to complete, between 2019 and 2021! Creating another entire codex is something I dream about immensely and would love to make a reality someday, but I currently lack the time to dedicate to it, as it would require years of work!

I have many personal projects involving full-page illuminated manuscripts on various subjects that are waiting to be painted, and I will indeed be working for a museum soon, but I can’t talk about it yet…!

Thank you, Marie, for your availability, your infinite kindness, and for carrying on a wonderful tradition with such love, passion, and expertise.

For now, yours truly, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and we’ll see you in future posts and on social media.

Entretien avec l’enlumineuse Marie Lefèvre

Au cœur d’une tradition ancestrale de feuille d’or, de pigments broyés à la main et d’une patience quasi monastique, Marie Lefèvre a choisi de redonner vie à l’art ancien de la miniature.

Dans son extraordinaire atelier Expecto Pigmentum, chaque miniature est le fruit d’un équilibre parfait entre rigueur historique et sensibilité contemporaine. Des feuilles manuscrites, puisant leurs dessins dans le patrimoine médiéval, s’animent jour après jour sous les mains expertes de Marie Lefèvre, qui s’inspire de tout ce qui l’entoure pour créer d’étonnantes miniatures.

J’ai eu le plaisir et l’honneur de m’entretenir avec Marie Lefèvre afin d’en apprendre davantage sur son travail inestimable.

- Quels sont les principaux défis techniques que vous rencontrez dans la création de

magnifiques miniatures ?

L’enluminure est un art qui s’organise en une succession d’étapes, réalisées au Moyen Âge par différentes personnes : les scriptoria et les ateliers comptaient copistes, qui s’occupaient de la calligraphie, doreurs, dessinateurs, enlumineurs, chacun ayant sa tache.

Aujourd’hui, je réalise toutes ces étapes seule et cela nécessite la maîtrise de techniques variées: la préparation des pigments, le travail de calligraphie, la pose de la feuille d’or et bien sûr les techniques picturales qui diffèrent en fonction de l’époque et du style d’enluminure. La seule difficulté technique qu’il m’arrive parfois de rencontrer lorsque je crée une enluminure est l’étape de la pose de l’or sur gesso. Le gesso est un enduit à base de colle de poisson, de sucre, de pigment blanc qui se montre parfois capricieux, en fonction de la température et de l’hygrométrie ambiantes. Il peut amener des difficultés pendant la sa pose, s’il fait très chaud et sec et qu’il sèche trop rapidement, mais aussi pendant la pose de la feuille d’or s’il ne colle pas assez et même après, lors de l’étape du brunissage avec une pierre d’agate polie montée sur un manche qui a pour but, en la frottant sur la feuille d’or, de rendre l’or davantage lisse et brillant.

- Travaillez-vous encore avec du parchemin comme aux XIVe et XVe siècles, ou préférez-vous le papier moderne ?

Je travaille sur parchemin, c’est un support que j’ai découvert en commençant l’enluminure et qui ne cesse de m’émerveiller. Le parchemin a un intérêt que le papier n’a pas, pour l’enluminure: étant de la peau animale, il est imperméable, permet donc à la peinture d’être seulement posée dessus et d’exprimer toute la lumière des pigments. Le papier, lui, absorbe la peinture et la rend plus terne, moins lumineuse. J’ai essayé quelques fois l’enluminure sur papier mais je préfère de très loin travailler sur parchemin, il fait pour moi partie intégrante de ce que représente une enluminure et c’est un matériau qui nécessite un savoir-faire qu’il faut préserver !

- Consultez-vous parfois des codex originaux dans les archives ou les bibliothèques ?

J’ai déjà eu l’occasion de consulter des manuscrits datants des VIIIè, XIè, XIVè et XVIè siècles à la

Bibliothèque nationale de France et à la bibliothèque d’Angers. Observer les manuscrits d’époque a plusieurs intérêts: en tant qu’enlumineur, cela permet de pouvoir comprendre les techniques picturales et de remarquer des détails que l’on ne distingue pas sur les numérisations disponibles sur internet, même lorsqu’elles sont de très bonne qualité. On peut donc comprendre comment a peint l’enlumineur, quels pigments il a utilisés, analyser l’ordre dans lequel il a travaillé, voir de ses yeux le moindre trait. C’est quelque chose de très enrichissant, de pouvoir se prêter à cet exercice, de très inspirant également, et il y a encore tellement de manuscrits que j’aimerais consulter, à la BnF bien sûr mais également dans d’autres bibliothèques car les trésors sont partout!

- Y a-t-il des maîtres enlumineurs du passé que vous admirez particulièrement et qui

vous inspirent?

Ayant eu la chance d’aller par trois fois voir l’exposition sur les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry au château de Chantilly il y a quelques mois, je me dois de parler du travail de dessin et d’enluminure époustouflant des frères de Limbourg, pour lesquels j’ai une admiration sans limite!

J’aime beaucoup également le travail des enlumineurs connus comme le Maître de la Cité des Dames, le Maître de Boucicaut, Maître Honoré, pour ne citer qu’eux…

Voir des manuscrits enluminés par des femmes, car elles existaient et étaient plus nombreuses que ce que l’on peut imaginer, au Moyen Âge, m’émeut particulièrement, je pense par exemple à Jeanne de Montbaston, qui a enluminé le célèbre « Roman de la Rose » à la fin du XIVè siècle.

Je pense également à tous les enlumineurs anonymes qui ont dédié leur vie à la copie et à l’ornementation de manuscrits, comme, parmi tant d’autres, les moines qui ont copié et enluminé au cours du VIIIè siècle le Livre de Kells, l’un des manuscrits les plus précieux au monde et parmi mes préférés, qui témoigne d’un savoir-faire, d’un style et d’une histoire inestimables.

- Existe-t-il des matériaux anciens difficiles à trouver ou qui ne peuvent plus être utilisés

aujourd’hui?

Pour revenir sur le parchemin, c’est aujourd’hui un matériau rare, difficile à trouver, surtout de la qualité du parchemin qu’on trouve dans les manuscrits médiévaux, qui est d’une grande finesse et d’une grande douceur, tant du côté fleur (extérieur de la peau) que du côté chair (intérieur de la peau).

Parmi les matériaux compliqués à obtenir se trouvent les couleurs d’origine végétales en général, comme par exemple le vert de vessie et le folium. Le blanc de plomb est aussi un autre exemple de pigment difficile à trouver car définitivement interdit à la vente en France et en Europe.

- Combien de temps vous faut-il en moyenne pour créer une page enluminée ?

C’est quelque chose de compliqué à estimer, tout dépend du style d’enluminure, car certains, comme le style dit « insulaire » (style des manuscrits enluminés en Irlande et en Grande-Bretagne entre le VIè et le début du IXè siècle) par exemple, demandent plus de temps de réalisation que d’autres.

Le temps de travail passé sur une page dépend également de sa grandeur ainsi que de la quantité de détails à peindre ! Ma double page enluminée sur l’incendie de Notre-Dame, qui mesure en tou 60cm de large et 38cm de haut, m’a demandé 550 heures de travail, recherches, dessin, calligraphie, dorure et peinture compris. Pour donner un autre exemple, une page que j’ai réalisée récemment, plus petite et sur laquelle apparaît le château de Chantilly, m’a pris 96 heures de dorure et de peinture.

- Comment le rythme lent et méditatif de votre travail influence-t-il votre créativité ?

C’est une question très intéressante ! Quand je commence à travailler sur une enluminure, je débute par les recherches, qui sont déjà à elles-seules un voyage dans le temps, car je suis amenée à consulter les numérisations de très nombreux manuscrits, pour trouver des détails, des mises en page, des motifs qui m’inspirent. Ensuite vient le travail de dessin, qui me permet de sélectionner ce qui aura retenu mon attention lors de mes recherches, qui est un travail préparatoire important pour lequel je m’enferme en moi-même pour organiser la composition, placer les détails, concrétiser l’idée que j’ai dans la tête.

Une fois qu’arrive le moment de poser la feuille d’or, de peindre, de calligraphier, c’est un vrai voyage intérieur et même spirituel qui commence, qui s’étend sur des jours, des semaines, parfois des mois et qui se poursuit même lorsque je n’ai pas le pinceau à la main, penchée sur mon parchemin. Il m’arrive souvent de rêver d’enluminure la nuit, de voir des motifs de fleurs, de spirales, d’entrelacs dans mes rêves. L’inspiration est partout, même lorsque je vais marcher dans la nature chaque jour et que je vois un écureuil dans un arbre, le motif du givre sur une feuille en hiver, les couleurs d’un lever de soleil…

Chaque couleur posée sur le parchemin, chaque coup de pinceau, est un pas sur le chemin de ce voyage intérieur, car durant toutes ces heures, je me retrouve seule avec mon travail et cela me permet de réfléchir profondément, de méditer, de démêler mes pensées et de forger de l’intérieur ce que je souhaite transmettre par l’enluminure sur laquelle je travaille. Quelques soient les problèmes rencontrés dans la vie, les émotions qui peuvent me traverser au cours d’une journée, je me perçois toujours comme un générateur de lumière, je transforme tout ce que je pense et ressent en beauté et en lumière, car c’est bien cela que signifie « enlumineur » : « éclairer/mettre en lumière ». À chaque enluminure que je crée, je dédie une partie de mon existence et je confie une partie de mon âme et c’est ce que je trouve le plus merveilleux dans cet art.

- Avez-vous des projets futurs, peut-être un codex complet de votre création ou une collaboration avec un musée dont vous aimeriez nous parler?

J’ai déjà réalisé un manuscrit d’une quinzaine de pages, en style insulaire inspiré du Livre de Kells et sur le thème d’un conte tiré du monde de Harry Potter, qui m’a demandé un an et demi de travail entre 2019 et 2021 ! Créer à nouveau un codex entier est quelque chose qui me fait énormément rêver et que j’aimerais pouvoir concrétiser un jour mais je manque actuellement de temps pour m’y consacrer car cela me demanderait des années de travail !

J’ai beaucoup de projets personnels de pleines pages enluminées sur divers sujets qui attendent que je les peigne, et je vais effectivement travailler pour un musée prochainement mais je ne peux pas encore en parler…!

Merci, Marie, pour votre disponibilité, votre infinie gentillesse et pour perpétuer une si belle tradition avec tant d’amour, de passion et de savoir-faire.

Pour l’instant, bien à vous, Michelangelo Buonarroti. À bientôt dans de prochains articles et sur les réseaux sociaux.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €

In Italia c’è anche Ivano Ziggiotti: miniatore che si fa i colori da solo, scrive e decora con penne d’oca su pergamena. Sicuramente lo trovi nel web. Ha pubblicato: “I segreti dell’Ars Illuminandi” e ha prodotto parecchi libri miniati. Buona domenica.

"Mi piace"Piace a 1 persona

grazie Neda, non ne ero a conoscenza. Adesso cerco un po’ di informazioni a riguardo

"Mi piace"Piace a 1 persona