Non portar danari ai preti: Dio sa quel che ne fanno

Ho sempre praticato l’elemosina. Lo so che non è una cosa molto nota: la mia fama immeritata da tirchio pare abbia insabbiato nel corso dei secoli il fatto che in realtà fossi assai generoso, più di quanto possiate immaginare.

Oramai son morto e lo posso dire senza temere di peccare di vanagloria, la miglior virtù dei saccenti.

Elargivo spesso danari a chi si trovava in difficoltà mentre evitavo di dar soldi alla Chiesa. Tutto quello sperperare e dilapidare ricchezze della curia romana che avevo avuto modo di comprovare di persona troppe volte, non m’andava gran che a genio.

Dopo la morte del mi babbo Ludovico e del mi fratello Giovan Simone, il mi nipote Lionardo mi scrisse raccontandomi di voler fare un pellegrinaggio a Loreto per l’anima del padre in Purgatorio. Il pellegrinaggio m’andava più che bene ed era una cosa che anch’io volentieri praticai a patto però che fosse un voto da onorare.

In caso contrario avrei preferito che i soldi spesi per quel viaggio e per l’elemosina lasciata in loco li avesse offerti a qualcuno che ne avesse bisogno “perché portar danari a’ preti, Dio sa quel che ne fanno”.

Dell’andare a Loreto per tuo padre, se e’ fu boto, mi pare da sodisfarlo a ogni modo; se gli è per ben che tu voglia far per l’anima sua, io darei più presto quello che tu spenderesti per la via, costà, per l’amor di Dio, per lui, che fare altrimenti: perché portar danari a’ preti, Dio sa quel che ne fanno

Dalla lettera che scrissi al mi nipote Lionardo il 7 aprile del 1548

Per il momento il vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

Don’t bring money to priests: God knows what they do with it

I have always practiced almsgiving. I know it’s not a well-known thing: my undeserved reputation as a stingy seems to have covered up over the centuries the fact that I was actually very generous, more than you can imagine.

Now I’m dead and I can say it without fear of sinning vainglory, the best virtue of know-it-alls.

I often gave money to those in difficulty while avoiding giving money to the Church. All that squandering and squandering of the Roman Curia’s wealth, which I had had the opportunity to personally verify too many times, didn’t sit well with me.

After the death of my father Ludovico and my brother Giovan Simone, my nephew Lionardo wrote to me telling me that he wanted to make a pilgrimage to Loreto for his father’s soul in Purgatory. The pilgrimage suited me more than well and it was something that I too gladly practiced, provided, however, that it was a vow to be honoured.

Otherwise I would have preferred that the money spent for that trip and for the alms left on the spot had been offered to someone who needed it “because they bring money to priests, God knows what they do with it”.

About going to Loreto for your father, if it was a rumor, it seems to me that I should satisfy him in any case; if it is for him that you want to do for his soul, I would sooner give what you would spend on the way, there, for the love of God, for him, than do otherwise: why bring money to the priests, God knows what they do with it

From the letter I wrote to my nephew Leonardo on 7 April 1548.

For the moment, your Michelangelo Buonarroti greets you by making an appointment for the next posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

5,00 €

-

Quel busto è mio? Nemmeno dopo due fiaschi di Trebbiano l’avrei scolpito così

🇮🇹E tutti a buttarsi a pesce sulla nuova fantomatica scoperta del busto del Cristo Salvatore in Sant’Agnese in Agone a Roma. Sarebbe mio quel Cristo lì, con quel volto inespressivo, anonimo e con quello sguardo perduto?… 🇬🇧And everyone’s jumping on the newly discovered bust of Christ the Savior in Sant’Agnese in Agone in Rome. Could…

-

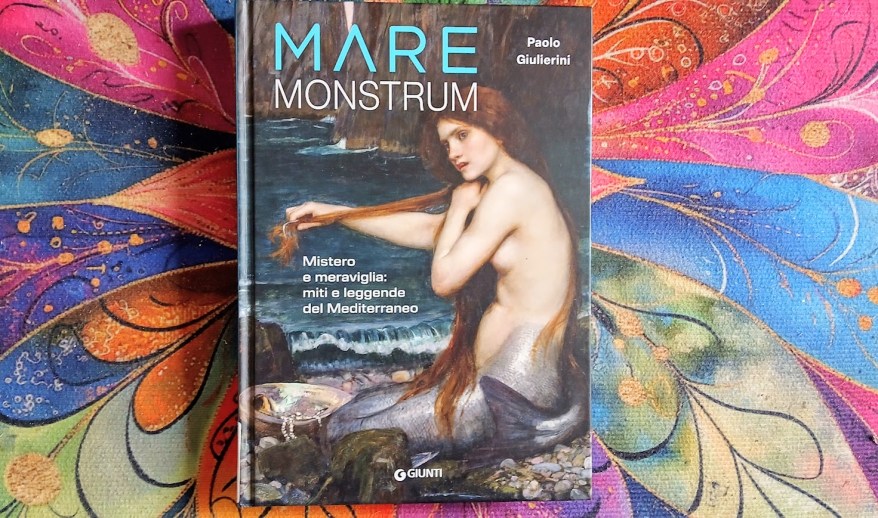

Mare Monstrum di Giulierini: il Mediterraneo oscuro che spiega il nostro presente

Con il libro Mare Monstrum, Paolo Giulierini, già direttore del Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, propone un viaggio colto e avvincente nel cuore del Mediterraneo, raccontato non come semplice spazio geografico ma come organismo vivo, mutevole e spesso inquietante…

-

Giornata Internazionale della Donna: 8 marzo 2026 musei e siti culturali statali gratis per tutte le donne

🇮🇹Domenica 8 marzo, le donne celebrano la loro giornata accedendo gratuitamente a musei, parchi e monumenti storici italiani. Un’occasione da non perdere… 🇬🇧On Sunday, March 8th, women celebrate their day with free admission to Italian museums, parks, and historical monuments. An opportunity not to be missed…