La lettera col Crocifisso nascosto

Vi propongo il retro di una lettera che scrissi a Cornelia Colonnelli, la vedova del mio assistente Francesco Urbino, morto prima del tempo il 3 gennaio del 1556.

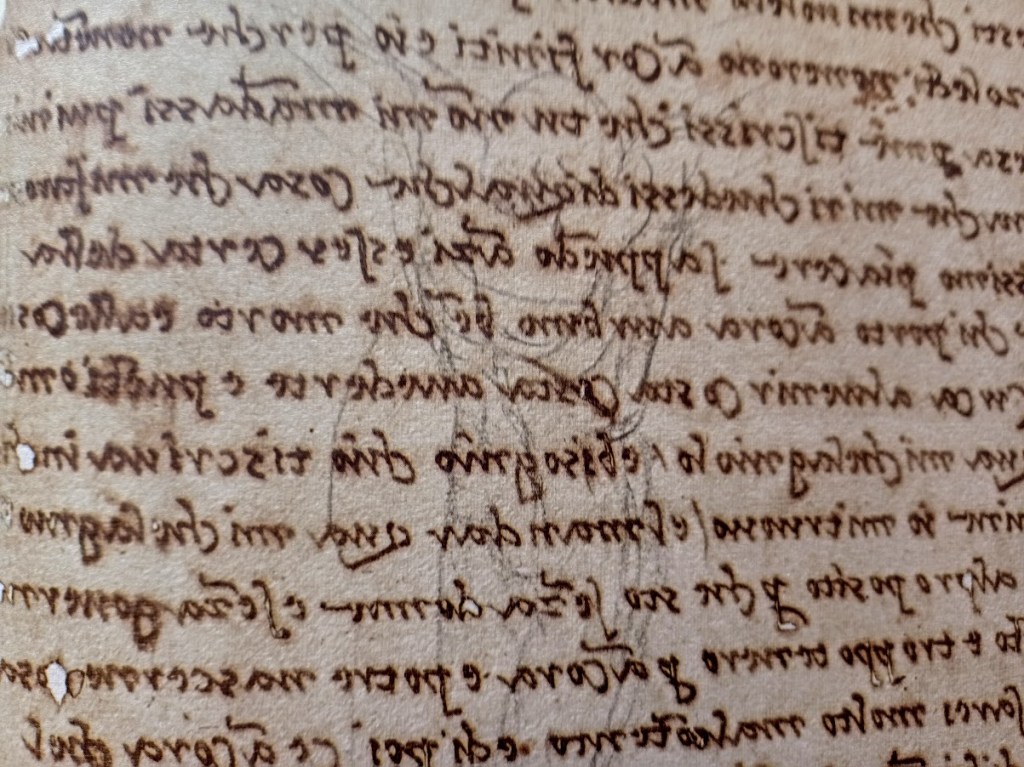

La cosa curiosa è che proprio sul retro c’è un mio disegno autografo di un Crocifisso. La croce ha una forma a Y ovvero è quella che viene chiamata Croce dei Bianchi e Cristo ha le braccia rivolte verso l’alto. Il capo chino sul petto pare oramai privo di vita mentre le gambe sono appena percettibili.

Se guardate bene vedrete dei veri e propri fori sulla carta in corrispondenza di alcuni tratti della grafia: ebbene, l’inchiostro con il tempo ha letteralmente consumato il foglio.

Che significato ha quel Crocifisso sul retro della lettera che scrissi a Cornelia il 28 marzo del 1557?

In realtà ha poca attinenza con il contenuto della missiva. Come vi ho raccontato più volte, la carta era un bene preziosissimo e per forza di cose se ne doveva fare un uso parsimonioso. Mi è capitato un gran numero di volte nel corso della vita di adoperare fogli per disegnare e poi riutilizzarli successivamente girandoli dall’altra parte per scrivere lettere o per studiare nuove figure.

Il foglio in questione fa parte del Codice Vaticano Latino 3211. Nella lettera riferivo a Cornelia che non era ancora tempo che prendessi il su figliolo Michelangelo a bottega: era troppo piccolo e speravo di non dover rimanere ancora a lungo a Roma. Pensavo infatti di partire durante l’inverno successivo alla volta di Firenze e lì di rimanerci. Una volta arrivato in città avrei potuto prendere con me il giovane ragazzo e insegnargli i rudimenti del mestiere.

Fatto sta che non partii per Firenze né in quell’inverno né in altra data, se non da morto.

Per il momento il vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

The letter with the hidden Crucifix

I propose the back of a letter I wrote to Cornelia Colonnelli, the widow of my assistant Francesco Urbino, who died prematurely on January 3, 1556.

The curious thing is that right on the back there is my autographed drawing of a Crucifix. The cross has a Y shape that is what is called the White Cross and Christ has his arms facing upwards. The head bent over his chest now seems lifeless while the legs are barely perceptible.

If you look closely you will see real holes on the paper in correspondence with some lines of the handwriting: well, the ink has literally consumed the sheet over time.

What is the meaning of that Crucifix on the back of the letter I wrote to Cornelia on March 28, 1557?

In reality it has little bearing on the content of the letter. As I have told you several times, paper was a very precious commodity and inevitably it had to be used sparingly. It has happened to me a large number of times over the course of my life to use sheets to draw and then reuse them later by turning them on the other side to write letters or to study new figures.

The sheet in question is part of the Vatican Latin Code 3211. In the letter I referred to Cornelia that it was not yet time for me to take his son Michelangelo to the shop: he was too small and I hoped not to have to stay in Rome for much longer. In fact, I was thinking of leaving during the following winter for Florence and staying there. Once I got to town I could take the young boy with me and teach him the rudiments of the trade.

The fact is that I did not leave for Florence either in that winter or on any other date, except when I was dead.

For the moment, your Michelangelo Buonarroti greets you by giving you an appointment at the next posts and on social networks.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

5,00 €

-

Caravaggio e il Seicento napoletano: 39 capolavori in mostra nel 2026 a Forte dei Marmi

🇮🇹Il Seicento napoletano dopo Caravaggio arriva a Forte dei Marmi: dal 27 marzo al 27 settembre 2026 il Forte Pietro Leopoldo I ospita 39 capolavori del Seicento napoletano… 🇬🇧 17th-century Neapolitan art after Caravaggio arrives in Forte dei Marmi: from March 27 to September 27, 2026, Forte Pietro Leopoldo I will host 39 masterpieces of…

-

21 febbraio 1508 – 21 febbraio 1513: il destino di Giulio II

🇮🇹21 febbraio 1508 e 21 febbraio 1513: vi racconto l’incredibile coincidenza tra l’inaugurazione della scultura in bronzo di Papa Giulio II a Bologna e la morte del pontefice cinque anni dopo, tra potere, arte e destino nel Rinascimento… February 21, 1508, and February 21, 1513: I’ll tell you about the incredible coincidence between the inauguration…