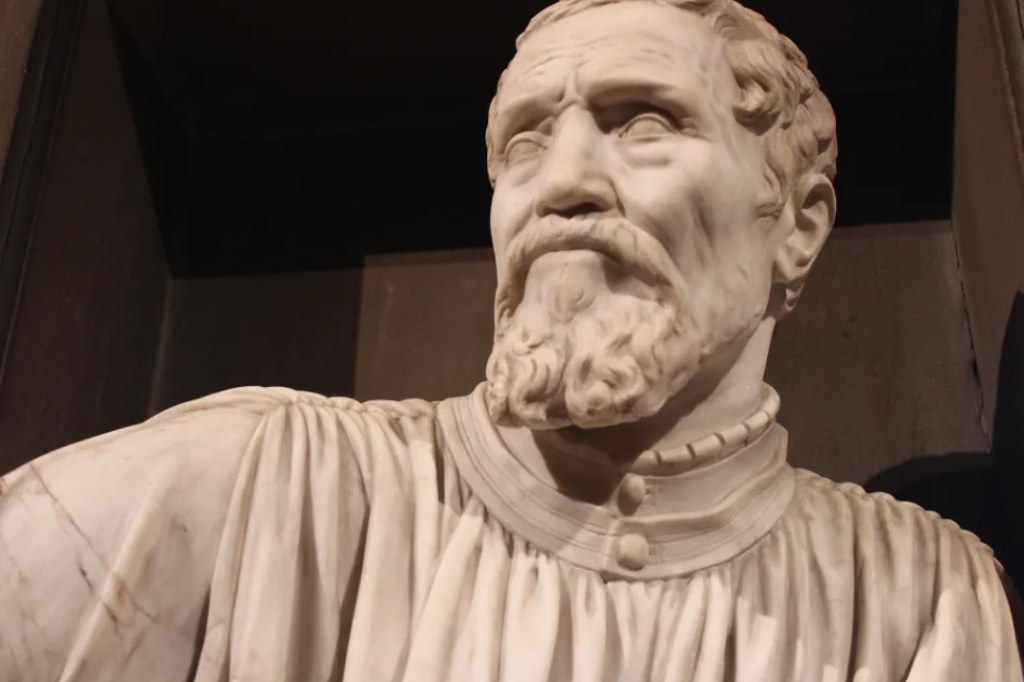

19 febbraio 1564: Roma cercò il denaro, il papa cercò i disegni

Il 18 febbraio 1564 chiusi gli occhi per l’ultima volta a Roma, nella mia casa di Macel de’ Corvi. Avevo quasi anni. Mi chiamavano “il Divino”, ma io mi sentivo soltanto un uomo che aveva dato tutto alla propria arte. Ecco cosa accadde il giorno dopo la mia morte.

Quando arrivai a fare i conti col Padreterno mi resi conto d’aver vissuto come un miserabile. Di danari ne avevo guadagnati assai nel corso della vita: papi, principi e banchieri mi avevano pagato profumatamente. Eppure vivevo con poco.

Sotto il letto tenevo nascosta una cassa con diecimila ducati d’oro. Una fortuna. Ma, alla fine dei conti, che m’importava?

Io dovevo creare e basta. Nemmeno avevo tempo per dedicarmi alle cose che con i soldi si possono comprare. Ben altri sogni erano i miei. Ben altri traguardi avevo da raggiungere.

Mi bastarono tre parole per fare testamento, come scrisse poi Giorgio Vasari:

«Lascio l’anima mia nelle mani di Dio, il corpo alla terra, la roba ai parenti più prossimi».

Nulla più.

L’ultimo appello per San Pietro

A dire il vero, due anni prima avevo lasciato anche qualche riga ai Deputati della Fabbrica di Basilica di San Pietro.

Avevo fatto appello al papa affinché si portasse a termine la nuova San Pietro così come l’avevo progettata. Dopo tanta fatica e tante arrabbiature gratuite, non potevo accettare che qualcuno osasse mutare il mio disegno.

Avevo dato la mia anima per quella basilica e per la gloria di nostro Signore. Non fosse trasformata.

Il pontefice allora era Papa Pio IV, al secolo Giovanni Angelo Medici di Marignano. “Ho dato la mia anima per questa basilica e per la gloria di nostro Signore, non sia trasformata..”.

La commissione del papa entrò in casa mia

Il sabato mattina, appena si diffuse la notizia della mia morte, e con il mio corpo ancora nel letto, arrivò a casa una commissione inviata dal papa.

Tra loro c’erano il commissario Alessandro Pallantieri e il notaio Roberto Ubaldini. Non fu possibile ai miei fedelissimi opporsi: l’autorità pontificia non si discuteva.

Il notaio iniziò a guardare dappertutto per redigere un inventario dettagliato.

Ma in casa non c’era molto.

Qualche coperta sdrucita. Biancheria nuova in una cassapanca inviata da Firenze dal mio nipote Lionardo. Poche stoviglie malmesse. E sotto il letto, quel baule con diecimila ducati.

Eppure i beni più preziosi non erano i danari.

Erano i disegni. I cartoni. Le tre opere in marmo ancora abbozzate.

I disegni e le sculture: il vero tesoro

Tra ciò che venne registrato figuravano: quattro pezzi di cartone; una Pietà appena iniziata; un Cristo con la croce, simile a quello della Minerva, un San Pietro in abito di papa e altri marmi ancora allo stato grezzo.

C’erano anche tante idee ancora su carta. Quelle furono portate via per ordine del papa. E lì iniziò l’ombra.

Il mio nipote Lionardo, erede universale, era in viaggio verso Roma. Giunse tre giorni dopo la mia morte e pretese la restituzione dei cartoni e della una cassa sigillata con il denaro.

La cassa gli fu resa. I cartoni no.

La lettera di Daniele da Volterra: “Si durera faticha a vederli…”

A raccontare quel momento fu Daniele da Volterra, che scrisse pochi giorni dopo a Vasari. Le sue parole erano amare: quei cartoni erano finiti in un luogo da cui sarebbe stato difficile rivederli, figuriamoci riaverli.

Si parlava di promesse, di copie, di intercessioni presso il cardinale Morone. Ma la realtà era chiara: il potere aveva messo le mani sulle mie ultime idee.

Il ritorno a Firenze e l’ultimo viaggio

Tre giorni dopo, Lionardo fece trasferire il mio corpo a Firenze: sarebbe stata la mia città ad accogliermi per l’ultimo riposo.

Io che avevo dipinto la volta della Cappella Sistina, scolpito la Pietà e il David, progettato cupole e sognato architetture celesti, tornavo alla terra che mi aveva generato.

Genio ricco, uomo povero

Morii con diecimila ducati sotto il letto ma con le mani sporche di marmo. Non vissi per il lusso. Non cercai agi. Non mi interessavano palazzi né banchetti.

Volevo creare.

E forse è questa la vera eredità che lascia un artista: non l’oro, ma l’inquietudine. Non la ricchezza, ma la visione.

Il giorno dopo la mia morte, Roma cercò il denaro. Il papa cercò i disegni. I miei cari cercarono il mio corpo.

Io avevo già consegnato l’anima.

E il resto, alla fine, era soltanto materia.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

February 19, 1564: Rome sought money, the Pope sought designs

On February 18, 1564, I closed my eyes for the last time in Rome, in my home in Macel de’ Corvi. I was almost 18 years old. They called me “the Divine,” but I felt like just a man who had given everything to his art. This is what happened the day after my death.

When I finally came to terms with the Almighty, I realized I had lived miserably. I had earned a lot of money over the course of my life: popes, princes, and bankers had paid me handsomely. Yet I lived on very little.

Under my bed, I kept a chest with ten thousand gold ducats hidden. A fortune. But, in the end, what did it matter to me?

I had to create, and that was it. I didn’t even have time to devote myself to the things that money could buy. I had very different dreams. I had very different goals to achieve.

Three words were enough for me to make my will, as Giorgio Vasari later wrote:

“I leave my soul in the hands of God, my body to the earth, my property to my closest relatives.”

Nothing more.

The final appeal for St. Peter’s

Actually, two years earlier I had also left a few lines to the Deputies of the Fabric of St. Peter’s Basilica.

I had appealed to the Pope to complete the new St. Peter’s as I had designed it. After so much effort and so much unnecessary anger, I could not accept that anyone would dare change my plan.

I had given my soul for that basilica and for the glory of our Lord. May it not be transformed.

The pontiff at the time was Pope Pius IV, born Giovanni Angelo Medici di Marignano. “I have given my soul for this basilica and for the glory of our Lord. May it not be transformed…”

The Pope’s Commission Entered My Home

On Saturday morning, as soon as the news of my death spread, and with my body still in bed, a commission sent by the Pope arrived at my house.

Among them were Commissioner Alessandro Pallantieri and Notary Roberto Ubaldini. My most loyal followers couldn’t oppose them: papal authority was beyond discussion.

The notary began searching everywhere to draw up a detailed inventory.

But there wasn’t much in the house.

A few tattered blankets. New linens in a chest sent from Florence by my nephew Lionardo. A few battered dishes. And under the bed, that trunk with ten thousand ducats.

And yet the most precious possessions weren’t the money.

They were the drawings. The cartoons. The three marble works still in draft form.

The Drawings and Sculptures: The Real Treasure

Among the things recorded were: four pieces of cartoon; a Pietà just begun; A Christ with the cross, similar to the one in Minerva, a Saint Peter in papal robes, and other marbles still in their rough state.

There were also many ideas still on paper. Those were taken away by order of the pope. And there the shadow began.

My nephew Lionardo, sole heir, was on his way to Rome. He arrived three days after my death and demanded the return of the cartoons and a sealed chest containing the money.

The chest was returned to him. The cartoons, however, were not.

The letter from Daniele da Volterra: “It will be hard to see them…”

The one who recounted that moment was Daniele da Volterra, who wrote to Vasari a few days later. His words were bitter: those cartoons had ended up in a place from which it would be difficult to see them again, let alone get them back.

There was talk of promises, copies, intercessions with Cardinal Morone. But the reality was clear: the powers that be had had their hands on my last ideas.

The Return to Florence and the Final Journey

Three days later, Leonardo had my body transferred to Florence: it would be my city that would welcome me for my final rest.

I, who had painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling, sculpted the Pietà and the David, designed domes and dreamed of celestial architecture, was returning to the land that had given birth to me.

Rich Genius, Poor Man

I died with ten thousand ducats under my bed but with my hands stained with marble. I did not live for luxury. I did not seek comfort. I was not interested in palaces or banquets.

I wanted to create.

And perhaps this is the true legacy an artist leaves: not gold, but restlessness. Not wealth, but vision.

The day after my death, Rome sought money. The Pope sought drawings. My loved ones sought my body.

I had already given up my soul.

And the rest, in the end, was only matter.

For now, yours truly, Michelangelo Buonarroti, bids farewell and invites you to join him in future posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €