La Gioconda di Leonardo da Vinci: analisi stilistica, significato e storia dell’opera

La Gioconda di Leonardo da Vinci non è soltanto il dipinto più celebre della storia dell’arte occidentale. È un’opera che continua a mutare con lo sguardo di chi la osserva e a generare nuove interpretazioni anche a distanza di oltre cinquecento anni.

La sua attrattiva non risiede solo nella perfezione tecnica, ma nella capacità di creare un rapporto diretto e quasi psicologico con l’osservatore. Guardare la Gioconda è come varcare le soglie di uno spazio sospeso, dove l’arte incontra la scienza, la filosofia e lo studio dell’animo umano.

Leonardo iniziò il dipinto intorno al 1503, probabilmente a Firenze, ma non lo considerò mai definitivamente concluso. Questo dato è centrale per comprenderne la complessità: la Gioconda non nasce come un semplice ritratto su commissione, ma come un laboratorio pittorico e mentale, un’opera su cui Leonardo sperimentò per anni le sue teorie sulla visione, sulla luce e sulle emozioni.

Contesto storico e culturale della Gioconda

All’inizio del Cinquecento Firenze era uno dei centri più avanzati d’Europa dal punto di vista artistico e intellettuale. Il Rinascimento aveva già prodotto figure come Botticelli e Verrocchio, ma Leonardo andò oltre, superando la rappresentazione idealizzata per cercare una verità più profonda. La Gioconda nasce in un periodo in cui l’arte non è più solo imitazione della natura, ma strumento di conoscenza.

Leonardo unisce pittura, anatomia, ottica e filosofia naturale. Ogni dettaglio del dipinto è il risultato di osservazioni scientifiche: il modo in cui la luce colpisce il volto, la struttura delle mani, la profondità dello spazio. Nulla è casuale. Tutto concorre a creare un’immagine che sembra di poter sentire respirare.

Analisi stilistica: la rivoluzione silenziosa di Leonardo

Dal punto di vista stilistico, la Gioconda rappresenta una frattura netta con la tradizione del ritratto quattrocentesco. La figura non è rigida né incorniciata in uno schema geometrico evidente. Il corpo è leggermente ruotato, le spalle non sono parallele al piano dell’osservatore e le mani sono adagiate con naturalezza. Questo movimento appena accennato dà vita alla figura e suggerisce una presenza reale, non artificiale.

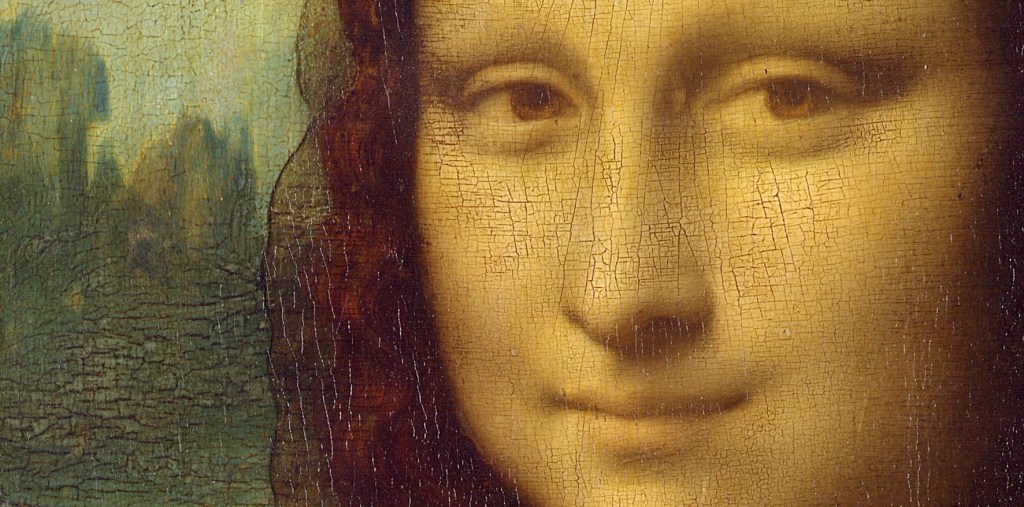

La tecnica dello sfumato è l’elemento più celebre e allo stesso tempo più difficile da imitare. Leonardo applica strati sottilissimi di colore, quasi impercettibili, che eliminano i confini netti tra luce e ombra. Il volto non è delimitato da linee, ma costruito attraverso passaggi graduali. Questo procedimento rende l’espressione instabile e ambigua, poiché l’occhio umano non riesce a fissarla in modo definitivo.

Il sorriso della Gioconda e la percezione visiva

Il sorriso della Gioconda è uno degli elementi più studiati della storia dell’arte. Non è un sorriso apertamente gioioso, né malinconico. È un’espressione intermedia, che cambia a seconda della distanza e dell’angolazione dello sguardo. Questo effetto è legato al modo in cui il cervello umano interpreta le informazioni visive: osservando la bocca direttamente, i dettagli più fini tendono a scomparire; guardando gli occhi, il sorriso sembra emergere.

Leonardo conosceva questi meccanismi grazie ai suoi studi sull’ottica e li applicò consapevolmente. La Gioconda non comunica un’emozione precisa, ma una condizione psicologica complessa. È questo che la rende così moderna e così distante dai ritratti idealizzati del suo tempo.

C’è da dire però che la Gioconda non è l’unica opera di Leonardo ad avere quel sorriso, anzi. In quasi tutti i suoi volti si ritrova la medesima posa della bocca: fateci caso. Diciamo che ‘il sorriso della Gioconda’ è stato parecchio mitizzato mentre gli altri sorrisi che ha dipinto non sono stati considerati in tal modo anche se sono in tutto e per tutto assimilabili.

Il paesaggio come estensione dell’anima

Alle spalle della figura si estende un paesaggio irreale, fatto di corsi d’acqua, ponti e rilievi montuosi. Il paesaggio non è simmetrico e non segue una prospettiva rigorosa, creando una leggera sensazione di instabilità. Questa scelta non è decorativa: il mondo naturale riflette lo stato interiore della figura.

Leonardo concepisce l’essere umano come parte integrante della natura. La fusione tra volto e paesaggio suggerisce una continuità tra microcosmo e macrocosmo, un tema centrale del pensiero rinascimentale. La Gioconda non è separata dal mondo, ma ne è una manifestazione.

Chi è la donna ritratta e perché l’identità conta fino a un certo punto

Tradizionalmente la Gioconda viene identificata come Lisa Gherardini, moglie di Francesco del Giocondo. Questa ipotesi è supportata da fonti storiche, ma non esistono prove definitive. Nel corso dei secoli sono state avanzate numerose teorie alternative, incluse interpretazioni simboliche e ipotesi di autoritratto.

Tuttavia, l’importanza dell’opera non risiede tanto nell’identità anagrafica della donna, quanto nella sua trasformazione in un’immagine universale. Leonardo non dipinge un individuo legato a un contesto specifico, ma una figura che trascende il tempo e lo spazio.

Perché la Gioconda si trova al Louvre

La presenza della Gioconda al Museo del Louvre è il risultato di un percorso storico preciso. Negli ultimi anni della sua vita, Leonardo si trasferì in Francia su invito del re Francesco I, che lo accolse come artista e intellettuale di corte. Leonardo portò con sé alcune opere a cui era profondamente legato, tra cui la Gioconda.

Dopo la sua morte, il dipinto venne acquistato dal sovrano e conservato nelle collezioni reali francesi.

Con la Rivoluzione Francese, queste collezioni divennero patrimonio pubblico e la Gioconda entrò ufficialmente nel museo del Louvre. Non si tratta quindi di un’opera sottratta all’Italia, ma di un passaggio avvenuto in modo legittimo nel contesto storico dell’epoca.

Il furto del 1911 e la nascita del mito moderno

Per secoli la Gioconda fu considerata un capolavoro, ma non ancora un’icona globale. La svolta avvenne nel 1911, quando il dipinto venne rubato dal Louvre. Il caso ebbe una risonanza internazionale senza precedenti e trasformò l’opera in un simbolo mediatico.

Il furto contribuì a costruire l’aura mitica della Gioconda, rendendola un’immagine familiare anche a chi non aveva mai visitato un museo. Da quel momento, il dipinto entrò definitivamente nell’immaginario collettivo mondiale.

La Gioconda oggi: conservazione, scienza e percezione di massa

Oggi la Gioconda è custodita in condizioni di massima sicurezza, protetta da vetri antiproiettile e da un sistema di controllo climatico costante. Le analisi scientifiche condotte nel tempo hanno rivelato la presenza di disegni preparatori e ripensamenti sotto la superficie pittorica, confermando quanto Leonardo lavorasse in modo lento e riflessivo.

Nonostante la distanza fisica imposta dalle misure di conservazione, l’opera continua a esercitare un fascino straordinario. Milioni di persone si recano al Louvre non solo per vedere un quadro, ma per vivere un incontro con un’icona culturale.

La forza della Gioconda risiede nella sua ambiguità. Leonardo non offre risposte, ma crea uno spazio di interrogazione. Ogni osservatore proietta sull’opera il proprio vissuto, le proprie emozioni, le proprie domande. E forse è proprio questo il vero capolavoro di Leonardo: aver creato un’opera che non smette mai di interrogare chi la guarda.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti e i suoi racconti vi da appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa: Stylistic Analysis, Meaning, and History

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is not only the most famous painting in the history of Western art. It is a work that continues to change with the gaze of the beholder and to generate new interpretations even after more than five hundred years.

Its appeal lies not only in its technical perfection, but also in its ability to create a direct, almost psychological connection with the viewer. Looking at the Mona Lisa is like crossing the threshold of a suspended space, where art meets science, philosophy, and the study of the human soul.

Leonardo began the painting around 1503, likely in Florence, but never considered it definitively finished. This fact is crucial to understanding its complexity: the Mona Lisa was not conceived as a simple commissioned portrait, but as a pictorial and mental laboratory, a work on which Leonardo experimented for years with his theories on vision, light, and emotions.

Historical and Cultural Context of the Mona Lisa

At the beginning of the 16th century, Florence was one of the most advanced centers in Europe, both artistically and intellectually. The Renaissance had already produced figures such as Botticelli and Verrocchio, but Leonardo went further, transcending idealized representation to seek a deeper truth. The Mona Lisa was born in a period in which art was no longer merely an imitation of nature, but a tool of knowledge.

Leonardo combines painting, anatomy, optics, and natural philosophy. Every detail of the painting is the result of scientific observation: the way light strikes the face, the structure of the hands, the depth of space. Nothing is accidental. Everything contributes to creating an image that seems to breathe.

Stylistic Analysis: Leonardo’s Silent Revolution

Stylistically, the Mona Lisa represents a clear break with the tradition of 15th-century portraiture. The figure is neither rigid nor framed by an obvious geometric pattern. The body is slightly turned, the shoulders are not parallel to the viewer’s plane, and the hands are placed naturally. This subtle movement brings the figure to life and suggests a real, not artificial, presence.

The sfumato technique is the most famous and at the same time the most difficult to imitate. Leonardo applies extremely thin, almost imperceptible layers of color, eliminating the clear boundaries between light and shadow. The face is not defined by lines, but constructed through gradual transitions. This process makes the expression unstable and ambiguous, as the human eye cannot capture it definitively.

The Mona Lisa’s Smile and Visual Perception

The Mona Lisa’s smile is one of the most studied elements in the history of art. It is neither an overtly joyful smile nor a melancholic one. It is an intermediate expression, changing depending on the distance and angle of the gaze. This effect is linked to the way the human brain interprets visual information: when looking directly at the mouth, the finer details tend to disappear; when looking at the eyes, the smile seems to emerge.

Leonardo knew these mechanisms thanks to his studies on optics and applied them consciously. The Mona Lisa does not convey a specific emotion, but a complex psychological state. This is what makes her so modern and so distant from the idealized portraits of her time.

It must be said, however, that the Mona Lisa is not Leonardo’s only work to feature that smile; on the contrary, almost all of his faces feature the same mouth position: notice. Let’s just say that “the Mona Lisa’s smile” has been highly mythologized, while the other smiles he painted have not been considered that way, even though they are entirely similar.

Landscape as an Extension of the Soul

Behind the figure lies an unreal landscape of streams, bridges, and mountains. The landscape is not symmetrical and does not follow a strict perspective, creating a slight sense of instability. This choice is not decorative: the natural world reflects the figure’s inner state.

Leonardo conceives the human being as an integral part of nature. The fusion of face and landscape suggests a continuity between microcosm and macrocosm, a central theme of Renaissance thought. The Mona Lisa is not separate from the world, but a manifestation of it.

Who is the woman portrayed and why identity matters to a certain extent?

Traditionally, the Mona Lisa has been identified as Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo. This hypothesis is supported by historical sources, but there is no definitive proof. Over the centuries, numerous alternative theories have been advanced, including symbolic interpretations and self-portraiture.

However, the importance of the work lies not so much in the woman’s chronological identity as in her transformation into a universal image. Leonardo does not paint an individual tied to a specific context, but a figure that transcends time and space.

Why the Mona Lisa is in the Louvre

The presence of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre Museum is the result of a specific historical process. In the last years of his life, Leonardo moved to France at the invitation of King Francis I, who welcomed him as an artist and court intellectual. Leonardo brought with him several works to which he was deeply attached, including the Mona Lisa.

After his death, the painting was purchased by the sovereign and preserved in the French royal collections.

With the French Revolution, these collections became public property, and the Mona Lisa officially entered the Louvre Museum. It is therefore not a work stolen from Italy, but rather a legitimate transfer within the historical context of the time.

The 1911 Theft and the Birth of the Modern Myth

For centuries, the Mona Lisa was considered a masterpiece, but not yet a global icon. The turning point came in 1911, when the painting was stolen from the Louvre. The case garnered unprecedented international attention and transformed the work into a media icon.

The theft helped build the Mona Lisa’s mythical aura, making it a familiar image even to those who had never visited a museum. From that moment, the painting entered the global collective imagination.

The Mona Lisa Today: Conservation, Science, and Mass Perception

Today, the Mona Lisa is kept in maximum security, protected by bulletproof glass and a constant climate control system. Scientific analyses conducted over time have revealed the presence of preparatory drawings and afterthoughts beneath the painted surface, confirming Leonardo’s slow and thoughtful approach.

Despite the physical distance imposed by conservation measures, the work continues to exert extraordinary fascination. Millions of people flock to the Louvre not just to see a painting, but to experience an encounter with a cultural icon.

The strength of the Mona Lisa lies in its ambiguity. Leonardo doesn’t offer answers, but rather creates a space for questioning. Each observer projects their own experiences, emotions, and questions onto the work. And perhaps this is precisely Leonardo’s true masterpiece: having created a work that never ceases to question the viewer.

For now, Michelangelo Buonarroti and his stories will be with you in future posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €