18 febbraio 1564: il giorno della mia fine terrena

La sera di venerdì 18 febbraio del 1564, i miei occhi si chiusero per non aprirsi più.

Daniele da Volterra, Diomede Lioni e il mio amato Tommaso de’ Cavalieri mi leggevano i passi dei Vangeli che narrano la Passione di Cristo. Le loro voci, lente come litanie, si fecero sempre più lontane e fievoli, finché non udii più nulla.

Erano per me tre grandi amici, uomini che mi sostennero e talvolta mi sopportarono fino all’ultimo dei miei giorni, e che presero le mie difese anche negli anni che seguirono la mia morte.

Cosa sarebbe stato, ai giorni vostri, il Giudizio Universale se a Daniele non fosse stato affidato l’ingrato compito di celare quelle che i prelati considerarono oscenità dopo il Concilio di Trento? Forse sarebbe stato distrutto alla stregua di altre opere, colpevoli solo di aver mostrato l’uomo a immagine e somiglianza di Dio.

Gli ultimi giorni nella casa di Macel de’ Corvi

Morii a Roma, nella mia casa di Macel de’ Corvi, alla vigilia dei miei ottantanove anni.

Già da lunedì 14 febbraio stavo male: una febbre che entrava nelle ossa e non mi lasciava dormire. Chi mi stava attorno sapeva che la fine era vicina. Lo sapevo anch’io.

Eppure, solo cinque giorni prima, mi davo ancora da fare con martello e scalpello sulla Pietà che oggi conoscete come Rondanini. La pietra era l’ultima cosa a cui mi aggrappavo.

Il 15 febbraio, verso le dieci di sera, provai perfino a salire a cavallo, sperando in un po’ di sollievo. Tornai presto indietro e mi sedetti davanti al fuoco: lì stavo meglio che a letto, in compagnia delle fiamme che danzavano.

Due giorni seduto al camino e tre a letto: da lì non mi rialzai più.

L’ultima lettera e l’attesa del nipote

Chiesi al mio fedele Daniele di scrivere al mio nipote Lionardo, affinché venisse subito a Roma. Avrei voluto rivederlo, parlargli delle mie ultime volontà. Ma le lettere viaggiavano lente, e più lento ancora fu il suo arrivo a cavallo.

Quando giunse, ero morto da tre giorni.

Già nel 1561 avevo sentito la fine avvicinarsi. Lavoravo senza tregua: Porta Pia per il papa, i disegni per la chiesa sulle rovine delle Terme di Diocleziano, il progetto della basilica di San Pietro. Presi carta e penna e scrissi a Lionardo di venire a Roma dopo Pasqua:

“Non menar teco gente che io abbia a tener qua in casa, perché ci ò donne e poche masserizie; e in fra due o tre dì ti potrai ritornare a Firenze, perché con poche parole ti farò intendere l’animo mio.”

In quell’estate, sentendo il terreno mancarmi sotto i piedi, distribuii molte elemosine. A Roma e a Firenze, feci dare trecento scudi alle famiglie più bisognose. Chi mi accusava d’esser spilorcio poco conosceva la mia storia: non spendevo per me, ma non ho mai negato aiuto a chi ne aveva necessità.

L’ultima malattia

Nel febbraio del 1564, il male non mi lasciò più.

“O Daniello, io sono spacciato, mi ti raccomando, non mi abbandonar.”

Il male durò cinque giorni: due al fuoco e tre a letto. Spirai il venerdì sera, con pace dell’anima.

Avevo vissuto quasi ottantanove anni: ai miei tempi, una rarità. Di vecchi come me se ne vedevano pochi per le strade.

Il corpo

Il 19 febbraio, il giorno dopo la mia morte, arrivò il notaio Ubaldini, mandato da Papa Pio IV per redigere l’inventario e il testamento. Il mio corpo fu portato nella Basilica dei Santi Apostoli.

Il pontefice avrebbe voluto che le mie spoglie restassero a Roma. Ma Cosimo I de’ Medici aveva altri piani e non intendeva cedere.

Quando Lionardo arrivò, si pensò a una strategia per riportarmi a Firenze. Il 7 marzo, un carrettiere di nome Simone da Berna mi caricò su una cassa rivestita di piombo. Per non destare sospetti, fui avvolto in una balla di mercanzie: sembravo un grande sacco di granaglie.

Così tornai nella mia città, non da vivo, ma da morto.

Vi ringrazio, in questa giornata, per ricordarvi ancora di me e della vita che condussi. Abbiate cura delle opere mie.

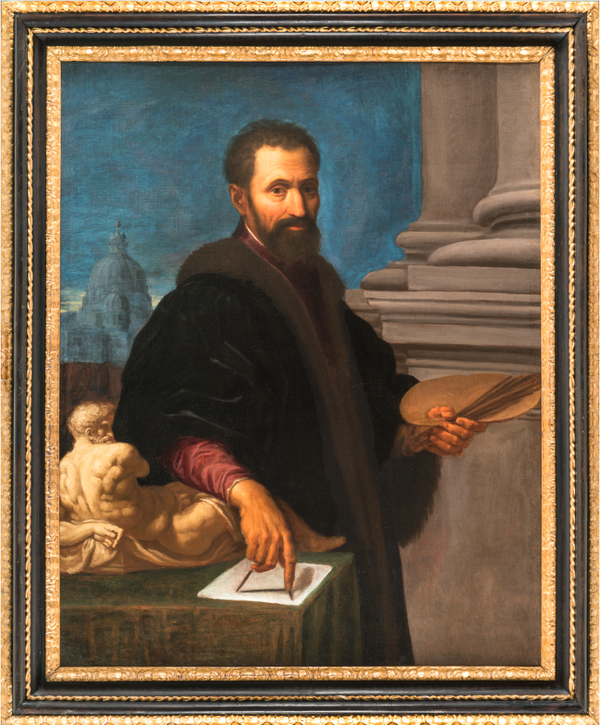

Il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti per il momento vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

February 18, 1564: The Day of My Earthly End

On the evening of Friday, February 18, 1564, my eyes closed and never opened again.

Daniele da Volterra, Diomede Lioni, and my beloved Tommaso de’ Cavalieri read to me passages from the Gospels that narrate the Passion of Christ. Their voices, slow as litanies, grew increasingly distant and faint, until I could no longer hear anything.

They were three great friends to me, men who supported me and sometimes tolerated me until my last days, and who defended me even in the years following my death.

What would the Last Judgment have been like in your day if Daniele had not been entrusted with the thankless task of concealing what the prelates deemed obscenities after the Council of Trent? Perhaps it would have been destroyed like other works, guilty only of having shown man in the image and likeness of God.

The Last Days in the House of Macel de’ Corvi

I died in Rome, in my house in Macel de’ Corvi, on the eve of my eighty-ninth birthday.

Since Monday, February 14th, I had been feeling ill: a fever that penetrated my bones and kept me awake. Those around me knew the end was near. I knew it, too.

And yet, just five days earlier, I was still busy with hammer and chisel on the Pietà you now know as the Rondanini. The stone was the last thing I clung to.

On February 15th, around ten o’clock in the evening, I even tried to ride a horse, hoping for some relief. I quickly returned and sat in front of the fire: there I felt better than in bed, in the company of the dancing flames.

Two days sitting by the fireplace and three in bed: from there I never got up again.

The Last Letter and the Wait for His Nephew

I asked my faithful Daniele to write to my nephew Lionardo, asking him to come to Rome immediately. I wanted to see him again, to tell him my last wishes. But the letters traveled slowly, and even slower was his arrival on horseback.

When he arrived, I had been dead for three days.

By 1561, I had already felt the end approaching. I was working tirelessly: Porta Pia for the Pope, the designs for the church on the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian, the project for St. Peter’s Basilica. I took pen and paper and wrote to Lionardo to come to Rome after Easter:

“Don’t bring with you people I have to keep here in my house, because I have women and few household goods; and in two or three days you will be able to return to Florence, because in a few words I will make you understand my heart.”

That summer, feeling the ground give way beneath my feet, I distributed many alms. In Rome and Florence, I gave three hundred scudi to the neediest families. Those who accused me of being stingy knew little of my history: I didn’t spend on myself, but I never refused help to those in need.

My Last Illness

In February 1564, the illness never left me.

“Oh Daniello, I’m done for, I beg you, don’t abandon me.”

The illness lasted five days: two by the fire and three in bed. I died on Friday evening, with peace of mind.

I had lived almost eighty-nine years: a rarity in my time. Few old men like me were seen on the streets.

My Body

On February 19th, the day after my death, the notary Ubaldini arrived, sent by Pope Pius IV to draw up the inventory and will. My body was taken to the Basilica of the Holy Apostles.

The pontiff had wanted my remains to remain in Rome. But Cosimo I de’ Medici had other plans and refused to give in.

When Lionardo arrived, a strategy was devised to bring me back to Florence. On March 7th, a carter named Simone da Berna loaded me onto a lead-lined crate. To avoid arousing suspicion, I was wrapped in a bale of merchandise: I looked like a large sack of grain.

So I returned to my city, not alive, but dead.

I thank you, on this day, for still remembering me and the life I led. Take care of my works.

Yours truly, Michelangelo Buonarroti bids you farewell for now, and looks forward to seeing you in future posts and on social media.

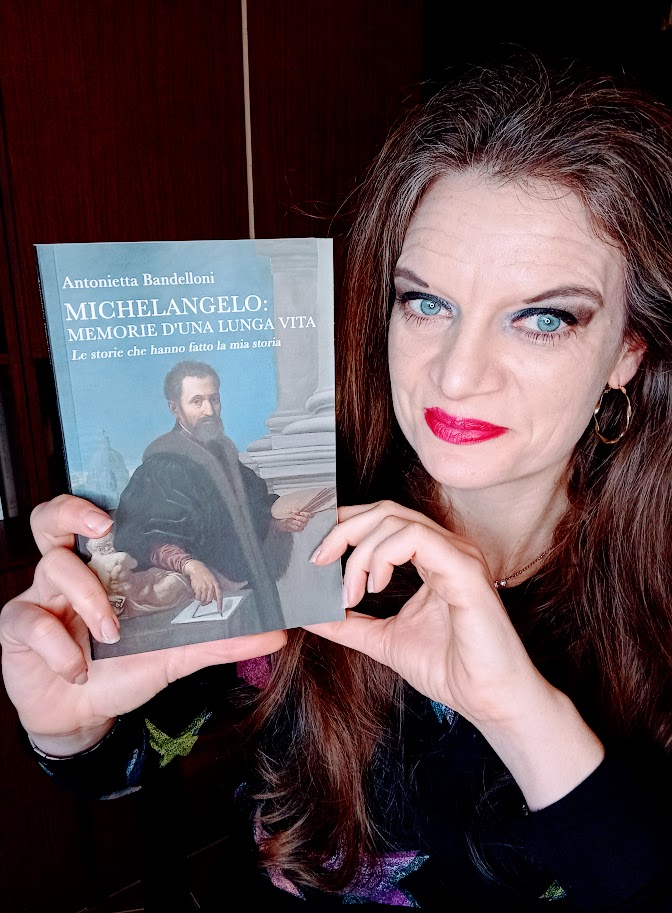

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €