Sotto gli occhi di tutti: il dipinto di Allori a San Martino e la seta di Lucca

La Cattedrale di San Martino racconta storie di epoche passate che hanno reso grande la città, ma per ascoltarle, o meglio, per vederle, bisogna prestare attenzione.

Nella Cattedrale di San Martino, sopra il quarto altare della navata sinistra, pochi si fermano a osservare il grande dipinto a olio su tela, alto oltre tre metri e largo più di due. Eppure quell’opera ha molto da narrare a chi ha voglia di ascoltare.

Raffigura la Presentazione di Maria al Tempio ed è un capolavoro del pittore fiorentino Alessandro Allori, ultimato nel 1602: cinque anni più tardi l’artista sarebbe passato a miglior vita.

Quell’opera, così come le altre dello stesso periodo, era stata commissionata dai reggenti della cattedrale nell’ambito di un progetto di riqualificazione che aveva anche uno scopo didattico: raccontare per immagini le storie mariane e cristologiche a chi non sapeva leggere. E all’epoca erano in molti a non saperlo fare.

Sul gradino più vicino all’osservatore si legge la firma dell’artista e la data di realizzazione dell’opera: AD MDIIC ALEXANDER BRONZINVS ALLORIVS CIV(S). Gioacchino, del quale si intravede il volto barbuto, e Anna, con l’abito rosso e il capo velato, accompagnano la piccola Maria — che all’epoca aveva tre anni, come raccontano i vangeli apocrifi — al cospetto del sacerdote del tempio.

Alcuni elementi dell’opera di Alessandro Allori, detto anche il Bronzino dal nome del suo maestro Agnolo Bronzino, saltano subito agli occhi: il bambino in basso a destra che gioca con il cane mentre mangia una mela, o l’uomo che suona la ghironda sul lato opposto, con le verdure dell’orto accanto alle gambe nude.

È però la magnificenza degli abiti indossati da diversi personaggi, con quei tessuti ricchi e preziosi, a sbalordire lo spettatore più attento.

Maria, a piedi nudi, sfoggia un capo che oggi definiremmo di alta sartoria, realizzato in damasco blu con pelliccia di ermellino sopra il gomito e impreziosito da bordure dorate.

Tessuti lucchesi

La ricchezza dei tessuti dipinti è sorprendente, ma non è casuale né frutto della sola fantasia dell’Allori. Lucca era nota in tutto il mondo allora conosciuto per la lavorazione della seta: fu infatti la prima città occidentale a produrre tessuti pregiati in grado di competere con quelli orientali, esportandoli in tutta Europa.

Già nel Trecento, i mercanti e gli artigiani della seta lucchesi portarono le proprie conoscenze nel resto della penisola, dando origine a nuovi centri di produzione.

L’artista, ben consapevole dell’importanza che il mercato tessile rivestiva per Lucca, lo pose al centro della scena, vestendo i personaggi con stoffe di straordinaria ricchezza. Alcuni di quei tessuti, molto probabilmente, ebbe modo di vederli e toccarli con mano proprio in città.

Non solo.

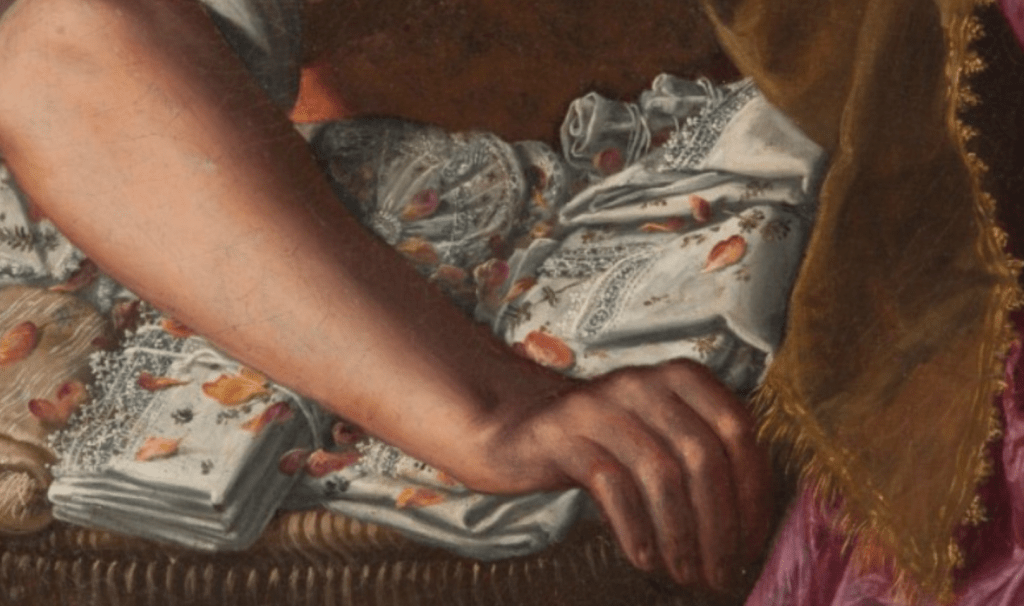

All’interno della cesta portata da un’ancella si scorge il corredo di Maria che le consentirà di accedere al tempio: capi confezionati con leggerissimi tessuti di seta, ricamati e bordati di pizzo.

Sul lato opposto del dipinto, un’altra ragazza più giovane — la cui età si intuisce dai capelli sciolti, concessi solo alle vergini o alle prostitute — sorregge tra le braccia una veste bianca ripiegata.

Quante cose può raccontare un dipinto, sotto gli occhi di tutti, se solo si avesse la pazienza di ascoltarlo.

For All to See: Allori’s Painting of San Martino and Lucca’s Silk

The Cathedral of San Martino tells stories of bygone eras that made the city great, but to hear them, or rather, to see them, you have to pay attention.

In the Cathedral of San Martino, above the fourth altar of the left nave, few stop to admire the large oil painting on canvas, over three meters high and more than two meters wide. Yet that work has much to tell those who are willing to listen.

It depicts the Presentation of Mary in the Temple and is a masterpiece by the Florentine painter Alessandro Allori, completed in 1602; five years later, the artist would pass away.

That work, like others from the same period, was commissioned by the cathedral’s regents as part of a redevelopment project that also had an educational purpose: to tell Marian and Christological stories through images to those who could not read. And at the time, many could not.

On the step closest to the viewer, the artist’s signature and the date of creation are inscribed: AD MDIIC ALEXANDER BRONZINVS ALLORIVS CIV(S). Joachim, whose bearded face can be glimpsed, and Anna, wearing a red dress and veiled head, accompany little Mary—who was three years old at the time, as the apocryphal gospels recount—to the temple priest.

Some elements of the work by Alessandro Allori, also known as Bronzino after his teacher Agnolo Bronzino, are immediately striking: the child in the lower right playing with his dog while eating an apple, or the man playing the hurdy-gurdy on the opposite side, with garden vegetables next to his bare legs.

But it is the magnificence of the costumes worn by various figures, with their rich and precious fabrics, that astounds the most attentive viewer.

Mary, barefoot, wears a garment that today we would call haute couture, crafted from blue damask with ermine fur above the elbow and embellished with gold trim.

Lucchese Textiles

The richness of the painted fabrics is astonishing, but it is neither accidental nor the product of Allori’s imagination alone. Lucca was renowned throughout the then-known world for its silk production: it was, in fact, the first Western city to produce fine fabrics capable of competing with those of the East, exporting them throughout Europe.

As early as the 14th century, Lucca’s silk merchants and artisans spread their knowledge throughout the peninsula, establishing new production centers.

The artist, well aware of the importance of the textile market for Lucca, placed it at the center of the scene, dressing the figures in fabrics of extraordinary richness. He most likely saw and touched some of these fabrics in the city itself.

And that’s not all.

Inside the basket carried by a handmaid, we see Mary’s trousseau, which will allow her to enter the temple: garments made of the lightest silk fabrics, embroidered and trimmed with lace. On the opposite side of the painting, another, younger girl—whose age is discernible from her loose hair, a custom only afforded to virgins or prostitutes—holds a folded white robe in her arms.

How much a painting can tell, right before everyone’s eyes, if only we had the patience to listen.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €