Antonio Reine: intervista allo scultore contemporaneo tra marmo, arte antica e passione

Ci sono incontri che non si limitano a raccontare un percorso artistico, ma consentono di avere a che fare con una visione del mondo, con un’idea di arte vissuta come necessità vitale.

L’intervista che ho avuto il piacere di fare ad Antonio Reine, scultore spagnolo contemporaneo, appartiene a questa categoria rara e preziosa.

Nelle sue parole emerge un’alta concezione della scultura come disciplina totale, come d’altro canto sempre l’ho intesa io. Un’arte fatta di studio incessante, sacrificio, rispetto assoluto per la materia e fedeltà a una tradizione che affonda le radici nell’arte classica e rinascimentale.

Reine non parla mai di talento come dono fine a se stesso, ma come responsabilità. Non considera il marmo un semplice materiale, ma un banco di giudizio che non ammette superficialità.

Scultura in legno di cedro, policromata a olio

Altezza: 1,46 m. (Nelle immagini l’opera è ancora allo stadio del legno non finito)

Dall’infanzia trascorsa a modellare la plastilina allo stupore davanti alla Cappella Sistina, dalla formazione accademica tra Spagna e Italia fino al dialogo costante con i grandi maestri del passato, il suo racconto è quello di una vocazione maturata nel tempo, alimentata dallo studio e dalla determinazione.

Antonio Reine si muove con gli attrezzi del mestiere in mano, con consapevolezza tra memoria e presente, cercando in ogni nuova scultura il superamento di sé.

A seguire vi propongo l’intervista integrale: buona lettura.

Quando è nato il suo amore per la scultura? È una passione che ha fin da bambino o è qualcosa che è maturato con il tempo?

Ho sempre sentito una forte attrazione per le arti plastiche. Da bambino modellavo piccole figure con la plastilina e, per diversi anni, vinsi a scuola il concorso di disegno del presepe natalizio.

Ma fu intorno ai tredici o quattordici anni che accadde qualcosa di decisivo: per caso mi capitò tra le mani un libro di storia dell’arte. Sfogliandolo, ricordo ancora lo stupore provato aprendo una doppia pagina con una veduta panoramica della Cappella Sistina. Rimasi senza parole.

Da quel momento iniziai ad approfondire e mi innamorai dell’arte greca, del Rinascimento, del Barocco e dell’Ottocento. Da allora non ho mai smesso di leggere, visitare musei e studiare questi periodi.

C’è stato un momento ben preciso in cui ha compreso che la scultura sarebbe diventata la sua strada?

È stato un processo graduale. Ci si orienta verso questa direzione già nel momento in cui, dovendo scegliere, si preferisce il percorso umanistico a quello scientifico.

In seguito ho frequentato il Liceo Artistico presso la Scuola d’Arte di Cadice, poi il Grado Superiore di Scultura a Granada e infine l’Accademia di Belle Arti all’Università di Salamanca, dove ho avuto l’opportunità di svolgere l’Erasmus a Roma.

Spesso familiari e persone vicine cercano di farti cambiare idea, facendoti credere che morirai di fame. Io rispondo sempre che non è la professione in sé il problema, ma la persona. Di calciatori ce ne sono molti, ma guadagnano tutti allo stesso modo? Ecco la risposta.

A quel punto era evidente che non avrei potuto fare altro se non la scultura. Ho sempre seguito il cuore prima della ragione e, col passare del tempo, questa convinzione non ha fatto che rafforzarsi.

Busto in marmo greco (Thasos), grandezza naturale

Dimensioni: 45 × 35 × 27 cm

Prima di mettersi a lavorare su un blocco di marmo o un pezzo di legno, già sa esattamente cosa andrà a realizzare o si lascia guidare in qualche modo dalle sensazioni del momento cambiando dettagli o stravolgendo la sua idea di partenza?

Quando realizzai la mia prima opera in marmo e compresi l’enorme sforzo che richiede questo materiale, promisi a me stesso che non avrei più scolpito il marmo se non per opere che lo meritassero davvero dal punto di vista scultoreo. Vale a dire: che la forma fosse capace di emozionare di per sé, e non per il materiale in cui è realizzata.

Per questo motivo, ogni volta che lavoro un blocco di marmo parto sempre da un modello precedentemente modellato, che mi consente di valutare il risultato finale della forma. Se non emoziona, non la trasferisco nel marmo.

Inoltre il marmo è un materiale costoso: una figura a grandezza naturale può richiedere un blocco che supera facilmente i 5.000 euro. Non è saggio indulgere nel romanticismo dell’improvvisazione, perché un errore può compromettere irrimediabilmente il blocco. Come è noto, il marmo non ammette errori.

L’unico spazio che lascio all’improvvisazione riguarda l’accentuazione di alcune zone, ma sempre partendo da una forma già definita con la massima fedeltà nel modello preparatorio.

Cosa preferisce scolpire, legno o marmo?

Senza dubbio il marmo. Per me — e per molti altri — rappresenta il summum della scultura. È una delle forme d’arte più elevate ed esigenti.

Il marmo è la regina delle pietre: un materiale durevole, dalla struttura omogenea e dalla grana fine, capace di accogliere dettagli impensabili. Il suo colore bianco — nel caso del marmo di Carrara o di quello greco — consente una lettura perfetta delle forme e, a seconda dell’incidenza della luce, restituisce superfici sempre diverse, rivelando nuovi dettagli a ogni variazione luminosa.

Processo di modellazione. Materiale: argilla. Dimensioni: grandezza naturale

Vorrebbe che chi guarda le sue opere cogliesse lo stesso significato che ha voluto attribuire lei o predilige che ciascuno le interpreti a seconda del proprio personale sentire?

Credo che ognuno di noi abbia una storia personale diversa e che, di conseguenza, osservi il mondo attraverso un proprio filtro, dando origine a molteplici interpretazioni.

Non cerco quindi una trasmissione del messaggio in modo univoco o cristallino; preferisco suggerire piuttosto che definire, affinché l’opera rimanga inesauribile.

C’è un artista del passato al quale si sente particolarmente legato?

Scolpire la figura umana in marmo senza pensare a Michelangelo è impossibile. Con ogni probabilità è il principale responsabile del fatto che io sia diventato scultore.

Dalla prima volta in cui vidi le sue opere e lessi la sua biografia, non ho mai smesso di studiarne la figura. Tutti gli stili che mi affascinano hanno un legame con lui: dall’Ellenismo, di cui si nutrì profondamente — il Laocoonte, il Torso del Belvedere — fino ad altri autori che amo, come Carpeaux o Rodin.

La sua personalità è così travolgente da costituire per me una fonte inesauribile di ispirazione. Ogni volta che scolpisco un’opera in marmo, leggo un libro su Michelangelo. Amo il modo in cui la lettura riesce a trasportarti in altre epoche e in altri luoghi; conoscere le sue difficoltà e le sue sofferenze mi aiuta a proseguire nel lavoro.

Quando qualcuno acquista un suo lavoro poi probabilmente le capiterà di non poterlo rivedere più. Cosa prova uno scultore nel sapere che un lavoro al quale ha dedicato tanta dedizione inizia un nuovo percorso in mani altrui? Non le dispiace un po’ separarsene?

All’inizio mi dispiaceva separarmi dalle mie opere. Oggi penso che veniamo al mondo senza nulla e senza nulla ce ne andiamo.

In fondo, le arti plastiche esistono per essere contemplate, così come la musica per essere ascoltata. Non è un caso che molti artisti, sentendo avvicinarsi la fine della propria vita, donino gran parte delle loro opere a collezioni pubbliche, affinché l’arte possa raggiungere più persone e non restare privilegio di pochi.

C’è una sua opera della quale è particolarmente orgoglioso?

No, almeno in termini di forma. Ogni nuova scultura nasce con l’intento di superare la precedente, non per soddisfare il cliente, ma per una convinzione personale e per principio. Credo che, quando non si dà consapevolmente il massimo, si finisca per tradire se stessi.

Una delle chiavi della felicità è sentire di avanzare. Per questo, la mia opera migliore deve ancora arrivare: sarà la prossima.

Che consiglio sente di dare a un giovane appassionato di scultura che vuole trasformare questo suo amore in un mestiere?

La prima domanda che farei è se sarebbe disposto a dormire per strada pur di essere scultore. Una scelta di questo tipo non deve lasciare spazio ai dubbi. Bisogna sapere con certezza che, se non ti dedichi alla scultura, alla pittura, alla musica — a ciò che senti veramente —, sarai infelice per tutta la vita.

Solo con questa consapevolezza si possono affrontare tutti i dispiaceri che il percorso comporta.

Una volta presa questa decisione, è fondamentale lasciarsi guidare dal maestro con cui si sente maggiore affinità. I suoi consigli, frutto dell’esperienza, possono risparmiare anni di tentativi ed errori.

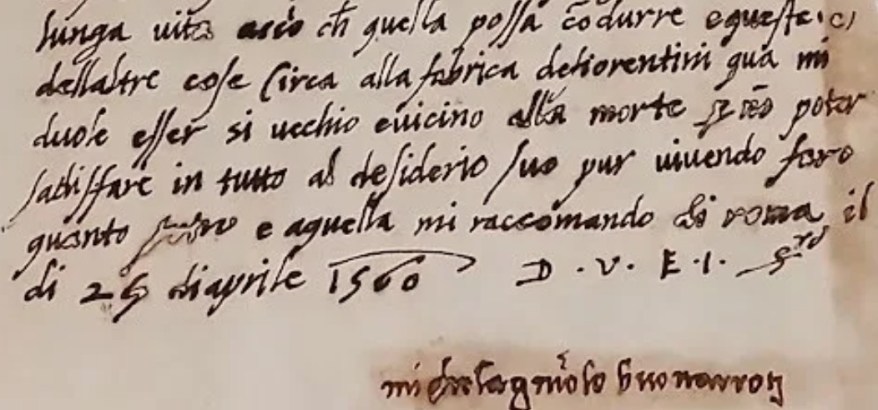

Io leggo continuamente, soprattutto scritti e lettere di artisti che hanno già attraversato ciò che altri stanno vivendo oggi: molti di questi libri sono vere e proprie guide.

Dove si trova il suo laboratorio nel caso qualcuno voglia contattarla per vedere i suoi straordinari lavori?

Attualmente vivo a Cadice, in Andalusia, Spagna, anche se non escludo un trasferimento in Italia — Carrara, Pietrasanta o Firenze. È un desiderio che coltivo da anni: il luogo in cui la scultura in marmo viene maggiormente praticata e apprezzata, e un paese al quale mi sento profondamente legato.

Grazie Antonio per la sua generosa disponibilità.

Per il momento il sempre vostro Michelangelo Buonarroti vi saluta dandovi appuntamento ai prossimi post e sui social.

Antonio Reine: Interview with the Contemporary Sculptor: Between Marble, Ancient Art, and Passion

There are encounters that don’t simply recount an artistic journey, but allow us to engage with a vision of the world, with an idea of art experienced as a vital necessity.

The interview I had the pleasure of conducting with Antonio Reine, a contemporary Spanish sculptor, belongs to this rare and precious category.

His words reveal a lofty conception of sculpture as a total discipline, as I have always understood it. An art made of relentless study, sacrifice, absolute respect for the material, and fidelity to a tradition rooted in classical and Renaissance art.

Reine never speaks of talent as a gift in itself, but as a responsibility. He doesn’t consider marble a mere material, but a platform for judgment that brooks no superficiality.

From his childhood spent modeling clay to his awe before the Sistine Chapel, from his academic training in Spain and Italy to his constant dialogue with the great masters of the past, his story is one of a vocation that has matured over time, nourished by study and determination.

Antonio Reine moves with the tools of his trade in hand, mindfully balancing memory and the present, seeking self-improvement in each new sculpture.

Below is the full interview: enjoy.

When did your love for sculpture begin? Is it a passion you’ve had since childhood, or is it something that has developed over time?

I’ve always felt a strong attraction to the visual arts. As a child, I sculpted small figures with clay, and for several years, I won the Christmas nativity scene drawing competition at school.

But it was around the age of thirteen or fourteen that something decisive happened: by chance, I came across an art history book. Leafing through it, I still remember the amazement I felt when I opened a double-page spread with a panoramic view of the Sistine Chapel. I was speechless.

From that moment, I began to delve deeper and fell in love with Greek, Renaissance, Baroque, and 19th-century art. Since then, I’ve never stopped reading, visiting museums, and studying these periods.

Was there a specific moment when you realized that sculpture would become your career path?

It was a gradual process. You begin to gravitate toward this direction when, faced with a choice, you prefer the humanities to the sciences.

I later attended the Art High School at the Cadiz School of Art, then the Advanced Sculpture Degree in Granada, and finally the Academy of Fine Arts at the University of Salamanca, where I had the opportunity to do an Erasmus exchange in Rome.

Family members and loved ones often try to change your mind, making you believe you’ll starve. I always answer that it’s not the profession itself that’s the problem, but the person. There are many footballers, but do they all earn the same amount? That’s the answer.

At that point, it was clear that I couldn’t do anything other than sculpt. I’ve always followed my heart before reason, and as time passed, this conviction only strengthened.

Before starting to work on a block of marble or a piece of wood, do you already know exactly what you’re going to create, or do you let yourself be guided in some way by the sensations of the moment, changing details or distorting your initial idea?

When I created my first piece in marble and understood the enormous effort this material requires, I promised myself that I would never sculpt marble again unless it was truly sculptural. That is, if the form was capable of moving in itself, and not because of the material it’s made of.

For this reason, every time I work a block of marble, I always start from a previously modeled model, which allows me to evaluate the final result. If it doesn’t excite me, I don’t transfer it to marble.

Furthermore, marble is an expensive material: a life-size figure can easily cost over €5,000 in a block. It’s unwise to indulge in the romanticism of improvisation, because a mistake can irreparably compromise the block. As is well known, marble does not tolerate mistakes.

The only room I leave for improvisation concerns the accentuation of certain areas, but always starting from a shape already defined with the utmost fidelity in the preparatory model.

What do you prefer to sculpt, wood or marble?

Without a doubt, marble. For me—and for many others—it represents the pinnacle of sculpture. It is one of the highest and most demanding art forms.

Marble is the queen of stones: a durable material, with a homogeneous structure and fine grain, capable of accommodating unimaginable details. Its white colour – in the case of Carrara or Greek marble – allows for a perfect reading of the shapes and, depending on the incidence of the light creates ever-changing surfaces, revealing new details with every change in light.

Would you like those who view your works to grasp the same meaning you intended, or do you prefer that each person interprets them according to their own personal feelings?

I believe that each of us has a different personal history and, consequently, observes the world through our own filter, giving rise to multiple interpretations.

Therefore, I don’t seek to convey a message in a univocal or crystalline way; I prefer to suggest rather than define, so that the work remains inexhaustible.

Is there an artist from the past to whom you feel particularly attached?

Sculpting the human figure in marble without thinking of Michelangelo is impossible. He is most likely the main reason why I became a sculptor.

Since the first time I saw his works and read his biography, I have never stopped studying him. All the styles that fascinate me have a connection to him: from Hellenism, which deeply influenced him—the Laocoön, the Belvedere Torso—to other artists I love, like Carpeaux or Rodin.

His personality is so captivating that it’s an inexhaustible source of inspiration for me. Every time I sculpt a marble work, I read a book about Michelangelo. I love the way reading can transport you to other times and places; knowing his struggles and sufferings helps me continue my work.

When someone buys one of his works, they’ll probably never see it again. How does a sculptor feel knowing that a work to which they’ve devoted so much is beginning a new journey in the hands of others? Aren’t you a little sad to part with it?

At first, I was sad to part with my works. Today, I think we come into the world with nothing and we leave with nothing. Ultimately, the visual arts exist to be contemplated, just as music exists to be listened to. It’s no coincidence that many artists, feeling the end of their lives approaching, donate a large portion of their works to public collections, so that art can reach more people and not remain the privilege of a select few.

Is there a work of yours that you’re particularly proud of?

No, at least in terms of form. Each new sculpture is born with the intention of surpassing the previous one, not to satisfy the client, but out of personal conviction and principle. I believe that when you don’t consciously give your all, you end up betraying yourself.

One of the keys to happiness is the feeling of progress. For this reason, my best work is yet to come: it will be the next one.

What advice would you give to a young sculpture enthusiast who wants to turn this love into a profession?

The first question I’d ask is whether he would be willing to sleep on the streets to be a sculptor. A choice like this should leave no room for doubt. You must know for certain that if you don’t dedicate yourself to sculpture, painting, or music—to what you truly feel—you will be unhappy for the rest of your life.

Only with this awareness can you face all the disappointments that come with the journey.

Once you’ve made this decision, it’s crucial to let yourself be guided by the master with whom you feel the greatest affinity. Their advice, born of experience, can save you years of trial and error.

I read constantly, especially the writings and letters of artists who have already been through what others are experiencing today: many of these books are true guides.

Where is your workshop located in case anyone wants to contact you to see your extraordinary works?

I currently live in Cadiz, Andalusia, Spain, although I haven’t ruled out a move to Italy—Carrara, Pietrasanta, or Florence. It’s a dream I’ve nurtured for years: the place where marble sculpture is most practiced and appreciated, and a country to which I feel deeply attached.

Thank you, Antonio, for your generous support.

For now, yours truly, Michelangelo Buonarroti, bids farewell and invites you to join him in future posts and on social media.

Sostienici – Support Us

Se questo blog ti piace e ti appassiona, puoi aiutarci a farlo crescere sempre più sostenendoci in modo concreto condividendo i post, seguendo le pagine social e con un contributo che ci aiuta ad andare avanti con il nostro lavoro di divulgazione. . ENGLISH: If you like and are passionate about this blog, you can help us make it grow more and more by supporting us in a concrete way by sharing posts, following social pages and with a contribution that helps us to move forward with our dissemination work.

10,00 €